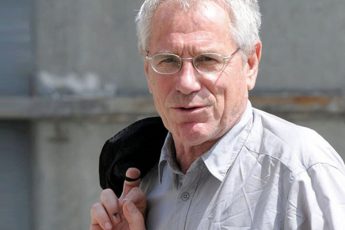

We interviewed Marian Ţuţui, artistic director of the Divanul Degustătorilor de Film şi Artă Culinară / Divan Film Festival, which takes place each year at the end of August in Cetate, Romania and is now in its fifth edition. We met with Marian to speak to him about the state of Balkan cinema, film festivals in the region and “Balkanism” in general.Marian Ţuţui is a film historian and researcher, currently teaching at Bucharest University and a former head archivist at the Romanian Film Archive. He is also the author of four books on cinema: “A Short History of Romanian Cinema” (2005, 2011, in Romanian and English), “Manakia Bros or the Image of the Balkans” (2005, 2009 in Romanian and English) and “Orient Express. Romanian and Balkan Cinema” (2008, 2011 in Romanian and English, awarded with Prize of the Romanian Film Critics Association). Since 1995 he has collaborated with film criticism magazines in Romania, USA, Great Britain, Moldova, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Hungary, Russia and Bulgaria.

Could you tell me about the origins and aims of the Divan Film Festival? Why film and food in the Balkans?

Mircea Dinescu [Romanian poet, ed.] bought this place with old buildings by the river Danube, restored them and founded the Cultural Port of Cetate. He wanted to organize several events there; concerts, seminars and a film festival. There was a producer who first had this idea together with Mircea, and they asked me to do the program since I had knowledge of Balkan cinema and some connections. In the beginning, it was something in Cetate, something about food…and the first edition was about the Balkans in general. I mean, the food must be Balkan, the films must be Balkan, but there was no theme or topic. We even organized something like seven days and seven Balkan countries, so every day we would have films from the same country and then food from that country and so on. The next year we expanded to countries where the river Danube runs, so the festival screened films from all these countries, and it was ten days…can you imagine that? Including food and music from each country. It was very difficult to do this, as I had to invite people from all those countries when I knew nobody from Ukraine or Slovakia. Then we began to think more about the festival’s specific characteristics – at this point it was just me and the Mircea Dinescu Poetry Foundation. There was already some criticism that in Cetate you can drink well and eat well but that it wasn’t very serious, so I said to them, look, we have to be more pragmatic. Mircea and Masha didn’t want a competition, so I suggested we do a symposium/conference on the study of Balkan cinema, keeping the general topic of Balkan cinema as the focus of the festival, but each year with a different topic for the symposium. We tried to use the geographical location of Cetate – by the river Danube, near the borders of Bulgaria and Serbia -, and combine it with the hosts’ talents and capacities. For instance, Mircea Dinescu is a vineyard owner, a gourmet and a chef – a lover of Balkan cuisine -, so in a way, it was almost unavoidable to choose the combination of Balkan cinema and food. However, Romanians don’t like to be considered in the Balkans, Croatians feel very upset if you say they are in the Balkans. Even the Serbians do, not to mention the Slovenes. Only Bulgarians, Macedonians and Turks accept to be in the Balkans.

But when it’s about food, Bulgarian, Serbian, Greek or Turkish cuisine sound good to a Romanian; the best coffee is Turkish. If someone has Turkish blue jeans it’s not good, but if he spent an evening in a Turkish restaurant, this is fine. Moreover, we can talk about the Balkans and cinema in a positive light – there is Emir Kusturica and Theo Angelopoulos. I mean ex-Yugoslav cinema has always had a kind of a prestige, not only Kusturica and Makevejev, but also the Zagreb Animation School for instance. Greek cinema is not so bad, and more recently Turkish and Romanian cinema has emerged. When it’s about the Balkans, the general view is that they are good at cooking and in cinema.

What about the title of the festival?

There was a discussion about the title and in the beginning, it was in Romanian: Divanul Degustătorilor de Film şi Artă Culinară, meaning literally, “The festival of lovers of Balkan cinema and cuisine”. In Romania we say “degustator” [someone who tastes, ed.]. Then, we said, ok, it is not quite a festival so why not call it “Divan”? It’s a Balkan word, old-school, Turkish, probably used in most Balkan languages. It means gathering, a kind of council, but also denotes sofas, places where you can stay and feel relaxed. For some people that sounded very strange. In English we said “Divan Film Festival”. To an English speaker it may sound a bit oriental, he doesn’t understand what “Divan” means. However for Balkan people, it has a certain flavor in any Balkan country.

Who is involved in the organization of the festival and how is it funded?

The Dinescu Poetry Foundation is the organizer with a staff of four. They submitted the project to the Romanian National Film Center, the Romanian Culture Institute and even to the mayor of Craiova. From the beginning, we have received funding from the National Film Center, the Culture Institute, and lately from the mayor in Craiova. In the last few years, the TV channel 1000, which shows some Balkan films and is broadcasted in most Balkan countries, became our main supporter. Then, there are other sponsors, private companies, such as Metro. This year we had less money, and we tried to do what was possible. What I am proud of is that even though we don’t have a big budget compared with other events that receive funding from the National Film Centre, we were able to have thirty people from abroad. Other festivals like ours never have more than ten international guests, with hardly any big names.

Who are the festival’s audience? What kind of response did you notice? Where do the festival guests come from?

People come from Craiova, a nearby city, where some of them even spend their holidays. We have three concerts in six days… there is a beach by the Danube and people simply love to be there. They ask us several months ahead if and when the festival is taking place. I cannot say that I rely on these people to make the festival’s audience. However, even people from Craiova or the village attended some difficult films. And when I screened a comedy they didn’t come, so maybe they are sometimes disappointed. For instance, during the screenings when we had our Danube cruise this year, I was sure about the good effect, as we chose films for children and animation like in the previous years. In a way, we also rely a lot on critics, journalists and guests attending.

I was grateful for the quality of films that were sent to us this year. Bulgarian documentaries are brilliant. I have even shown some Serbian and Greek ones. I remember the audience being surprised to watch a marvelous animation from Bosnia or Albania which they found very strange. I think that even now we look to the West, often ignoring those near us – we look somewhere far away, not in the neighbor’s yard. Not to mention that in cinema theaters in Romania there was only one Croatian film screening in the last twenty years, one Bulgarian, one Greek, and two or three Turkish ones. At the moment, there is a Croatian television series being broadcasted, and of course Turkish soaps, but otherwise people can only have a glimpse of Balkan cinema at festivals. With Balkan film festivals, they have this opportunity. I am trying to explain to them that it is not only about the Romanian New Wave; the Turks are also present in Cannes and Berlin and they get awards each year. Also the Serbs are still strong, and sometimes there is Aida Begić or someone else from Bosnia who gets a big award.

What are the criteria for selecting films? Where do the films come from?

I try to go to some festivals in the Balkans and I am also following other festivals in the Balkans on the internet. Then, I have friends and I ask for their advice. I usually choose shorts, animation, fiction or documentaries which tend to be longer, new and well-made, so that people get an idea of what’s going on in the Balkans. The “new” can even be a bit older – since the festival has no competition, it doesn’t really matter. On the other hand, my aim is that at least some of the films, fiction films in particular, fit the theme of the festival, for instance “Escape from the Balkans” and escapism, Balkan humor for the “Comedy of the Balkans”, and this year “Heroes and Anti-heroes in the Balkans”.

When thinking about the theme for next year’s edition, I also rely on the expertise of my friends, critics and scholars from other Balkan countries. I ask them: “Do you have a good film in Bulgaria about trips, a road movie?” Although I watched a lot of Bulgarian films, I don’t remember a good Bulgarian road movie for instance. And then, there are some directors who write to me and ask me to watch their films.

For our third section, we select films about cooking, the Danube, or films about the Balkans made by foreign filmmakers. This year we had a very old film, Danube Destroys and Builds (Dunărea distruge şi clădeşte/Die Donau zerstört und baut, 1944), an Austrian-Romanian co-production directed by Ulrich Kayser. Some audience members had a strong impression after seeing what Romania and the banks of Danube were like during WWII, as they’re not accustomed to watching archival material. This time, I tried to show some old films and animations, even Romanian advertising with mythical heroes and all kinds of parodies. Here perhaps I am aided by my archival expertise.

In what ways do initiatives such as these bring awareness to and increase understanding of Balkan cinema?

That is difficult to say. I think with Kusturica and especially during the war in ex-Yugoslavia, there was isolation, an inward focus. Now there is a kind of reaction, they hate Emir Kusturica and they hate turbo-folk. Sometimes everything which is Balkan. In Romania, it seems that the Balkans don’t sound so bad, and maybe we took part in generating that acceptance. In Greece, they are very open, not to mention Turkey. For the Turks, the Balkans are still Europe and remind them of Ottoman times. The Turkish Minister of Culture is now spending a lot of money in Balkan countries. I think it’s a good time.

The festival in Pogradec, Albania, took up the idea immediately. Eno Milkani made a documentary about our festival and later asked for my permission to copy the idea as he wanted to organize a films festival himself. So, we have a kind of franchise in Albania. There are also other scholars, such as Electra Venaki from AltCine or Dina Iordanova and Nevena Daković who, like myself are interested in this concept.

There is a relatively new music festival in Bucharest called Balkanik which features contemporary bands from Romania which play 18th and 19th century-style Turkish music with traditional instruments – to many, this is strange, but there is actually an audience for this. Romania has cultural institutes in around fifteen countries; they are opening one in Beijing and Belgrade now. In the last two or three years, they have been doing a Turkish cooking festival in parks around Bucharest that is very popular – people come to eat all kinds of Turkish specialties. So, when it’s about food there is something good about the Balkans. In 1998, I wrote a book about the Manakia brothers, for which I was heavily criticized. Some even dubbed me a nationalist. However, specialists in other Balkan countries recognized its importance and now everybody is talking about the Manakia brothers. Probably it was this book, and the festival, now in its fifth edition, which have made some impact, and perhaps it is bigger than I thought. Really, I feel proud… until now, I was happy we had a place where specialists could meet, but now I realize it is something bigger. Of course there will always be a position in Romania or Croatia claiming that we are Latin and European, that we have nothing to do with Slavs or Turks, that our ancestors studied in Paris and Vienna and that the East is something dirty. All the same, people in Germany prefer to go to a Turkish or a Greek restaurant…

How do you see this festival in the next five years?

I have never really had the time nor reasons to think too far ahead in the future – I have always had pressing and urgent problems to resolve. For instance, the contribution from the National Film Center this year is smaller, so we have bigger problems covering the budget. I also have problems regarding the publishing of the book, because in the last few years, we have had to spend more money to publish the book in Romanian and English with the papers from the symposium.

Not many things can change as there is a certain capacity in Cetate, and now there is a period of crisis. I don’t think the festival can be bigger. There is also this distance problem: Cetate is a nice place, but it is 300 km away from the Bucharest airport. We were never able to use the international airport in Craiova. Sofia is closer, while Belgrade and Bucharest are the same distance from Cetate. I hope that the symposium will continue, and that we will be able to print the book and perhaps announce a call for papers in the future. I was glad we had Dina Iordanova and Nevena Daković this year, and that we have this collaboration with AltCine. We also had a young critic from the UK, Abbie Saunders, attending, an interesting voice among the Balkan guys. The festival has set up a co-production and some contacts in the past. TV 1000 has asked for my advice and expertise to choose some Balkan films from the festival to be included in their program. It is really a meeting place, it allows for opportunities to emerge that would not otherwise exist.

Probably, our obsession with the West is declining and we can now be normal and take a look around us. Years ago we had this excessive fascination for the West, constantly trying to be like the West. Today, Balkan cinema doesn’t sound so bad anymore; there are good directors, lots of awards, and Suleiman [Turkish TV series “Magnificent Century”, ed.] is showing in fourteen countries – only Seinfeld can be this successful, but in different places. I don’t think Seinfeld was ever screened in Afghanistan, but I am sure Suleiman is there.

Thank you for the interview.

Leave a Comment