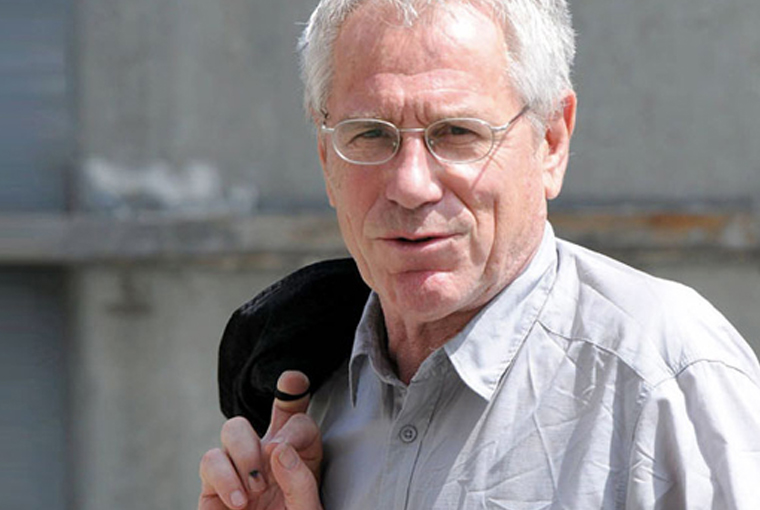

We met Želimir Žilnik at the Thessaloniki International Film Festival (October 31-November 9), where he was honored with the event’s lifetime achievement award during a screening of his 1969 film “Early Works”. Žilnik speaks about the Yugoslav Black Wave, his film “Fortress Europe” (2000) on European anti-immigration efforts, and discrepancies between Yugoslav reality and contemporary Serbia.

Was the Black Wave an artistic or a political movement?

The generation after the Second World War that started making films would call themselves the “New Yugoslavian Films Wave”. These are directors who were also very well-known in France. My generation was an even younger one, so we started making films 10 years after them – we started at the end of the 60s, when the first “new Yugoslavian film generation” had already created an important basis for new aesthetics.

In the 60s Yugoslavian socialism was at its peak, which was different and much more open than in the Soviet Union. We did not have dictatorship in art. On the contrary, during the 50s and the 60s there was a certain openness in Yugoslavia towards more humanistic approaches and cinema was accessible. I mean that we could have every film from anywhere in the world shown in our cinemas: people like Cassavetes or filmmakers from New York or elsewhere – we saw their works in the cinema. And people would go and watch films, at those times cinema was the only window to the world for us. We were well-informed and in this type of state socialism, politicians were often members of the cultural elite. For example, the minister of social affairs at the time was a film critic in Paris. Then he went to Spain during the Spanish civil war. In those years you could pass Belgrade and see Sartre or Picasso having coffee in the city. I myself remember running into Erich Fromm. People wanted to come and see this hopeful and progressive society that combined all values like workers’ liberties, workers’ rights. And my generation of filmmakers was criticized for not believing enough in the future. You should bear in mind that these films were a small part of film production at the time. Due to a special funding system built on self-investment where students were asked to co-produce etc., we could film the films we wanted and there was no censorship.

But after 7 years, the regime of Tito was shaken following the entrance of Soviet troops in Prague in 68. As you know, that occupation provoked massive demonstrations in universities and I filmed a documentary back then. At the time the society was shocked – hopes about state socialism staying as free and open-minded as it had been until then started to fade away. Political pressure emerged even with regard to films that had already been produced and released in the past. They were named “black films”. My film with the homeless people was my personal reaction to that ideological pressure and accusation. I wanted to mock them in their face. So, just to conclude we directors answered that our films were not pessimistic: we were just showing the contradictions that existed in a society that did not want to change. But wanting to change is important. With dogmas, they sought to conceal many sides of humans, notably their actual lives and destinies or the difficult but also painful struggles of wanting to establish a change in society. So, most of my own and my colleagues’ films were doing nothing else but researching and articulating this tense moment of the “human”.

And from the 70s on, the whole group of directors that produced new generation films, which were also very successful abroad, was stopped. Some of us went abroad, e.g. to France, I went to Germany. And soon this new dogmatism installed in Yugoslavia came in conflict with the economical system and the open foreign policy. So after six years, the pressure on art calmed down and many of us returned home. Still, this peaceful time lasted very few years and then in the middle of the 80s we would feel that the creativity of the system (especially after the end of Tito’s reign) was fading away and that we were about to face a new era of populism and nationalism. In ’85, six years before the war started, I made a film in which Belgrade is completely destroyed and Yugoslavia is divided. Some poor, devastated people are left behind, living in small rooms. The film was actually supposed to be taking place in 2041. New fascist dictators rise and rule, restricting all communication between the regions and ethnic groups of Yugoslavia. The main plot line is about two people waking up one morning and saying that they should rise up against this system. As you can imagine, making a film is complicated – at the time we used real film and negatives, so I was in the streets of Belgrade asking people who work as garbage collectors in the mornings to throw the garbage at midnight in the city center and then brought along actors to enter this image of a destroyed and abandoned Belgrade. People might have thought I am insane at the time, but I could just see where the country was heading to with all the people we were collaborating with. When young people see this film nowadays they think that I filmed it 3-4 years ago, but no, I had really filmed it before the war. People cannot believe it! If you see where you live and feel the people around you and what they think and how they react, this is an inspiration for film. During my long career as a filmmaker I have always been astonished by the fact that you can find much more reason and reality among ordinary people than among the people of political class. Just think about how many of these politicians that had been preaching Marxism and communism turned to new conservatism – even intellectuals did it. There were so many people that took part in this propaganda. It is just weird.

Do you believe that audiences have changed after the Yugoslav Wars?

The whole situation of film and media has changed. Of course now with the creation of new nations there are also different kinds of production. But even during the wars, and just after, there were possibilities to show things – I mean the desire to watch films that say things about reality did not vanish. People saw Tito among the Serbs, and other films. But during the wars, I would find myself in ridiculous and difficult situations at times, getting arrested and stuff. I am not saying that it was great suffering. But that’s how it was. And about films: whenever there was something authentic and away from the mainstream, there was interest among the media and festivals and people, even during the wars.

About your film “Fortress Europe”: how did you come up with its subject at that specific time?

I was invited by a critic in Italy to go and look at a new situation that was emerging on the Northern Italian border. Refugees from ex-Soviet countries were heading towards Slovenia and Italy and he thought that this was an important topic to make a documentary film about. So I went there, to the border between Slovenia and Italy close to Trieste, and also to a border crossing between Hungary and Austria. During the filming there were many issues since the people we filmed were held in detention centers – they we people observed by the police. We had to find them, and by the end of the day it was not so complicated as 60 out of 400 police officers from the area were married to Russian and Ukrainian women who had themselves tried to cross the borders illegally, being pushed by traffickers. So you would have those beautiful tall Russian and Ukrainian queens there. Another thing that is important is the fact that back then France and Spain needed about half a million people to work in agriculture, to pick fruits. So the police officers said “come with us and we will show you, we are pretending to stop the flow of the people crossing illegally”. The film shows what they really did. We spent some nights there and we saw they would stop people and ask to look at their hands. Those who looked like hard-working people with peasant hands would be put aside and sent to their “masters” in Europe. So my film had to show the great contradictions that existed. The collapse of socialism and its consequences made it hard for these countries to compete in the global economy.

The most important motivation for making this film was showing the disillusionment of people who had believed the state propaganda about capitalism and democracy, and how all people have equal chances in Europe. The state encouraged all the clever and educated people to leave the country. Among them there were excellent architects and economists and engineers from Romania, Ukraine etc. And it’s funny because a few years earlier, if any of those people would have left the Soviet Union to go the West, they would have been hugged and welcomed in wonderful ways as talented, promising people. But now they were being stopped; only the worst criminals could go, wealthy people a big part of whom had held high political posts in the army, the police or the government. So, people started wondering if the West had any idea whom they were showing respect to. Anyhow, that’s how we made the film. What I want to say is that somehow and sometimes documentaries manage to document and reveal some topics that are hidden from the mainstream press.

What are you mostly concerned about today? The rise of nationalism or the increase of neoliberalism in Serbia?

Well, it is interesting to say that the way capitalism was applied in Serbia has actually failed. Living standards are worse than under the previous regime. And the most educated and motivated members of the younger generations are forced to leave the country because there are no jobs or opportunities for them. Back then, it was me and some more directors that had to leave for a while. But now it is 200 000 people who are forced to leave. Also, the political elite of the system prefers to stick to their ideology of national interests. And there is this propagandist manner of defending the idea of “nations” infiltrating society.

It might sound like a prophecy but I wonder if Europe will also break up into different parts because of economical instability. I guess that this would be a way to sustain this system that “stages democracy”…

Thank you for the interview.

Leave a Comment