A Tale as Old as Time

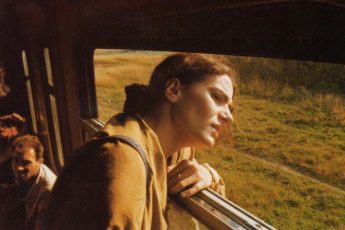

Aibeck Daiyrbekov’s The Song of the Tree (Darak yry, 2018)

Vol. 94 (April 2019) by Alice Heneghan

The Friday night stage at the old Wiesbadener Casino-Gesellschaft building at goEast 2019, played host to Kyrgyzstan’s first ever musical, The Song of the Tree. It tells the story of two forbidden lovers, kept apart by the suitor’s lack of status and position in a society where brute strength and riches buy respect. There are not a great deal of films coming out of Kyrgyzstan and so its presence at a German festival is welcome. Yet, director Aibeck Daiyrbekov’s hark back to the traditional folk tale of a damsel trapped between two different versions of male control in the modern climate of melting gender roles, is a bit of a limp towards the future of Kyrgyz cinema. In 2016, La La Land broke the box office and despite its lack of chemistry or charm, it at least explored a love story that was unconventional. Three years later, the modern musical has been taken in the opposite direction of progression and in doing so, fails to stand out against other Kyrgyz titles such as Centaur and Queen of the Mountains, which also deal with tradition but do so in a more dynamic fashion.

The story begins with a mother praying for her two sons who, along with the other young studs of the village, proceed to take part in a macho battle for the chief’s daughter. It is the youngest brother Esen (Omurbek Izrailov) who actually has a place in Begimai’s (Saltanat Bakaeva) heart, yet he is bullied away from his prize by the pugnacious Oguz (Jurduzbek Kaseivov). Immediately we see that a young, untrained boy without riches or great strength has no place in chief Bazarbai’s (Temirlan Smanbekov) sexist hierarchy. His insistence on the public wooing of his daughter and sacrifice of a sacred tree for a show of decadence, indicate his fixation on external appearances rather than interior emotions. Unsurprisingly, Begimai and Esen try to go against the social current but are separated until Esen is able to prove his worth and Bazarbai’s pride has driven him to desperation.

Despite his rejection, Esen’s fighting spirit only goes so far as to overcome boyish arrogance to an acceptable level of manly strength and marriage to a pretty wife. His journey to this point is bastioned by a pseudo-father figure while his mother sits at home losing her mind. His repeated tumbles and failures suddenly transform at one point into agility and strength, which unlock the doors to societies previously closed to him. Where exile and travel could have taken Esen’s character many places, the most that can be said is that he seems to overcome the question of pride. His mentor teaches that to learn how to fight one must learn how to fall, which is something Bazarbai struggles with until the very end. Nevertheless, if Daiyrbekov wanted to retell a tale already told so many, many times, he could have at least explored the self-destructive pride of Bazarbai, the loneliness behind Oguz’ ego or Esen’s failure to meet male norms, and the subsequent love between him and Begimai. Instead the film is comparable to a donkey-ride that plods through the motions and the Kyrgyz Mountains at a steady and pleasant pace.

To be fair to the film, the audience is treated to a striking soundtrack and a few unusual instruments and musical traditions. The actors sing well, and the songs are fittingly used as tools to advance the simple narrative with straightforward and relatable lyrics. Occasionally a few dance steps are performed, but most of the choreography consists of slow, steady movement that lends itself to the wide, panning shots of the epic Kyrgyz landscapes. Combined with the colorful and original clothing, particularly a psychedelic pink coat worn by a neighboring villain, the resulting images are very pleasing to the eye. The extreme mildness of it all, however, makes it just so regular. The action stinks of rehearsal, the roles are painfully prescribed and the plot utterly predictable with the requisite happy union and beginning of a new family foyer. The resulting film lacks feeling and passion, even energy. From 2005–2009, UNESCO were putting their efforts into safeguarding the Art of the Akyns, Krgyz traveling musicians and storytellers, a tradition that might have inspired a dynamic recital of events. In 2018, however, Daiyrbekov put his efforts to keeping his Kyrgyz musical as minimal and straightforward as its trite storyline.

If The Song of the Tree screens anywhere near you, then by all means, take a trip to somewhere new. Perhaps the escape into the past could provide a new perspective on the present. True, the story and the way it is told are average and unoriginal. But the cinematography is pretty. The soundtrack is unusual. And as Esen resists victorious revenge in favor of love, Bazarbai does at least regret his chauvinism.

Leave a Comment