Connective Tissues

Andrea Slováková’s Recovering Industry (Rekonstrukce průmyslu, 2015)

Vol. 70 (December 2016) by Rohan Crickmar

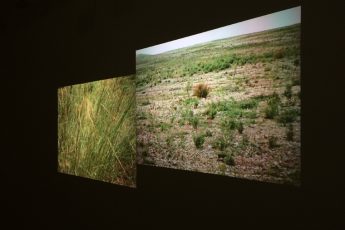

Like many of the best experimental films Andrea Slováková’s Recovering Industry uses a deceptively simple visual idea to explore the intricate relationships between different social spaces and the structures of power that they reflect. The title of the film astutely details that visual idea, whilst simultaneously suggesting a possible thesis from the director. The subjects of the film are those heavy industries that have managed to survive and thrive in the aftermath of the transition from Communism to capitalism in the Czech Republic. By filming various industrial locations around the country, as well as the ancillary industries (such as transport and communications) that are connected to the efficient operation of these industrial spaces, the director then gradually layers film upon film. Not only does this succinctly describe the complex matrix of industrial interdependencies at work around each of these sites, it also creates a beautiful filmic experience, in and of itself.

Andrea Slováková was born in 1981 in Slovakia, but studied Media at Charles University in Prague, the city that has since become her home. Training as a documentary filmmaker at FAMU in Prague, she has worked in a management capacity with the Jihlava International Documentary Film Festival, performed curatorial work for Doc Alliance Films and taught documentary history and practice at Masaryk University in Brno. What is fascinating about many of the documentary films that Slováková has completed since her debut Loos’ Box in 2004 is the unusual manner in which she has chosen to cover highly technical and scientific subject matters in a rigorously aestheticized way. What is more she is clearly a Czech filmmaker that is committed to working through many of the socio-political changes that have occurred post-1989, but predominately from a perspective that prioritizes the points where the political and the environmental intersect.

In Recovering Industry Slováková and her new DOP Lukáš Hyksa have shot three separate locations to serve as starting points for the three variations presented in the film. The first of these variations is a long shot of a chemical plant hunkered down in the center of rural greenery. The composition of the shot, its muted colors and the general flatness of the image, make it look like a 17th century Flemish landscape painting by the likes of Jacob van Ruyadael. This effect is further enhanced as the chemical plant becomes slowly smothered in ghostly plumes of white smoke. What industrial apparatus has been on display in this opening image appears to consist of iron and steel, but the next layer of the film pulls in closer to examine a red brick factory building on the interior of the complex. From this internal exterior the shot is further layered with a film of the machines of industry within the factory buildings. Once again Slováková and Hyksa pull in closer to the previous film by adding another layer of film that shows the close procedural workings of steam pistons. By this stage so much visual information has been densely packed upon the screen that the initial landscape has begun to resemble the detailed geometries of an industrial draughtsman’s work. Yet the filmmaker is still not finished with the image, for now her most audacious visual conceit begins to emerge. Not only are the layers of film recording the various elements of an industrial structure and its innards, but they also begin to connect this to spaces and structures that exist as a result of the industry. The final layers of film are the high rise blocks of workers’ residences, the mass of freight cars at a rail depot and the piping that evacuates the waste materials from the factory.

The second industrial image appears to be of some kind of hydro plant and layers up films of industrial platforms, bureaucratic offices, telecommunications infrastructures and the complex weave of road and rail infrastructure. By the end of this section of the documentary the layered image has taken on the alarming form of a vectoring Futurist realization of industrial schemata. The exquisite detailing of the image is most extravagantly achieved by the manner in which the layers of film seem to be bustling back and forth between each other within the frame, like so many workers upon the shop floor.

By the final variation Slováková’s need for repetition is wholly justified by the ingenuity of the drone film footage that Hyksa captures. In the previous two sections of the film the camera has assumed a fixed vantage point, capturing motion within the frame, but never moving the frame itself. But in capturing the rusted carcass of a coal mine and processing plant, the camera takes flight and the layering technique finds another level of complexity. With the camera liberated the layers of film now fall across one another from opposing directions and all possible angles. Canal tributaries, the cabling of coal carts, the far away shipyards, the torturous tangle of railroads, the glowing arteries of the power grid, all fall in upon one another, creating a truly mesmerizing sequence of film. Yet the most impressive aspect of this mobile film assemblage is the manner in which the industrial images, over time, mesh together at those precise points that reveal their intersecting dependencies. The coal cart locks with the canals in which waste runs off, as well as the rail sidings in which the rail cars await their loads. The railroads and the power grid map out an exoskeleton upon a skeleton, one perfectly laying atop the other. The railroads fall off into the boats waiting for them at distant foreign shipyards; the work performed upon the ships being powered by the energy lines that converge upon that site. The final layering of urban and suburban roads and residences only underscores this overwhelming idea of interconnectivity and interdependency.

It is somehow reassuring to see a documentary filmmaker so clearly concerned with the processes of industry that patently shape society. The ghost of Grierson would certainly approve. However, what makes Slováková’s work in this film ingenious is the degree of importance she also places upon the artistry of visual documentation. These are not simply images of industrial spaces, or layers of film without aesthetic correspondence, they are part of a documentary process that integrates experimental formalism with an interrogation of the socio-political structures that define effective industrial working environments. It is a work of film art as neatly constructed as the double meaning of its title.

Leave a Comment