“When You Break a Promise, You Lose Your Life.”

Beata Parkanová’s The Word (Slovo, 2022)

Vol. 125 (May 2022) by Jack Page

In the summer of 1968, notary Václav Vojíř’s world comes to an impasse. While taking the moral high ground, his refusal to join the Communist Party will rock the very foundations of his marriage and his family’s life in the small town in which they reside. The neighbors and other family members are less principally inclined, and their moral obligations fall short of any political conformity. Václav’s in-laws agree that if it maintains an equilibrium, is it really that bad to enlist? Ultimately, it is the entire Vojíř family that are punished for Václav’s ethical code. The Word is an exercise in how to uphold righteousness in the face of adversity and leave morally victorious even after losing.

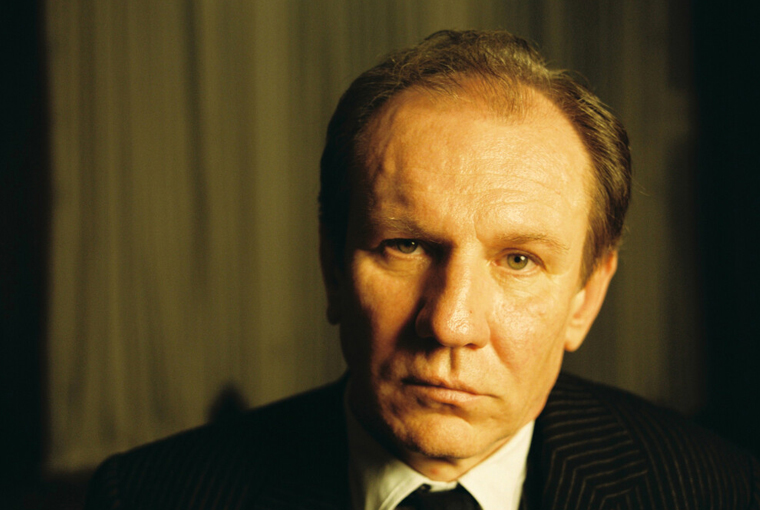

Václav (expertly portrayed by Martin Finger) is introduced as a man of simple pleasures in the opening frames of The Word. Shot just outside his window, a typewriter’s keys tap emphatically away in the background as the protagonist raises his blinds and basks in the sunlight that seeps through. He lingers a moment longer, relishing the warmth of the rays on his face before returning to his desk. Approaching his chair, he stops to admire his office’s artwork as if it was the most splendorous painting in the gallery. In the town, Václav’s name is synonymous with virtue. He takes pride in his work and his clients adore him. His advice is both fair and philosophical, counseling the most selfish and coldest of hearts so that both parties find an agreeable settlement. As a result of his honesty and gentlemanly methods, his legal practice is the most respected throughout the region. It is fair to say then, Václav’s character is unwavering and unwilling to succumb to corruption of any kind. His conduct is infallible and there is no doubt he will continue to resist the Communist Party that repeatedly intrudes on his sessions. That is until their threats leave him bedridden and depressed. Devoid of his personable nature, the once stand-up citizen is now a silent and unshaven mess. Where once he wore three-piece suits, he now appears shrunken and boyish in his baggy pajamas and unkempt hair, refusing to eat his supper.

At this point early on in the film, Václav’s authoritative wife Věra takes center stage. As small-town paranoia grips the family’s psyche, Věra is left to maintain the running of the household alone. At the news of her husband’s diagnosis at the psychiatric ward, Věra’s frustration manifests itself in helpless servitude. She begins to babble, rambling instructions at the miserable Václav: “Even here you should look after yourself.” She produces a folder filled with the children’s drawings for his inspection, complaining about his disheveled appearance. Věra’s try hard attitude and militant orders are played in a tragically vulnerable way by actress Gabriela Mikulková. It is the first instance wherein the audience are privy to the unguarded version of the character, a Věra that is willing to exhaust all possibilities before she concedes defeat in the failure to cure her husband. She is a masterfully complicated figure, blending shades of a stern parent, caring sister, and worried wife in every scene. Even after Václav’s period of mental illness, it was always Věra’s strength that the family’s solidarity was built upon.

The use of still photographs throughout The Word is an unexpected artistic flourish. Some of the tableaux mimic the cinematography of the scene – framing, camera angles – whereas others resemble still life and portrait photography. Various images focus on narrative events (the duplicitous clientele in Václav’s waiting room), whereas others are entirely extra-diegetic (a sun hidden by clouds, a vase of flowers). Some photographs denote the action relating to the plot (character confrontations) and others simply relay the abstract or figurative nature of a scene (the tears of an upset child, implying sadness). In the majority of portraits, the subject is always looking directly into the lens, breaking the fourth wall. Oddly, the photos do not seem to evoke the feeling of artifice, but rather nostalgia. They look as if they were taken by someone in the context of the film’s narrative setting in 1968, matching the aesthetic form in both color and tone. It is a fascinatingly bold choice that – when both types of images are mixed together – may not necessarily convey exactly what transpired on screen, but the impression or essence the director intended in the scene. These stills act as the film’s footnotes, supporting both plot and character development as well as lending The Word a personal touch, like the slideshow of a family album.

At the film’s humbling conclusion, the Vojíř household is relocated to an undisclosed location. The truck is filled to the brim with moving boxes, each family member squashed into what little space remains. In the driver’s seat, Václav’s daughter climbs upon her father’s lap and the family erupt into a merry folksong. As the credits roll, the young girl gazes outside the window at the world passing by. Unfazed, the Vojířs are not fearful or apprehensive of their next chapter. They remain untouched and untarnished by the Communist pressure groups as they do their own governing. Ultimately, everything they have is each other and everything they kept was their word.

Leave a Comment