Immigrant Locals

Daria Onyshchenko’s The Forgotten (Zabuti, 2019)

Vol. 108 (October 2020) by Colette de Castro

While the world watches Belarus, the opening film of the Molodist film festival in Ukraine reminds us of another unresolved conflict, one that could easily be overlooked after more than six years of war. Aptly titled, The Forgotten deals with the many victims of the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian conflict, and specifically those who come from cities in Eastern Ukraine occupied by separatists in the so-called Republics of the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts.

Nina (Maryna Koshkina) is a 30-year-old teacher who has just begun her teacher’s retraining in Luhansk where her husband Vasyli (Aleksey Gorbunov) has found a decent job. In the opening scenes she is shown in a school building, asking her way in Ukrainian to a teacher who snaps back that “we speak Russian here”. Language is a sensitive matter for Nina, who used to teach her native language before she came to live in Luhansk. At a dinner party with friends, an inebriated acquaintance says jeeringly to her across the table that she will “have to get used to speaking Russian now, not your farmers’ language”. These exchanges are believable, but one feels the scriptwriter has gone a little too far when Nina stands up to a Russian agent in the classroom for the reeducation program she is following.

Education, or a lack thereof, is an important theme in this film. Children are seen undergoing military training, and teachers with limited resources rely on old Russian textbooks. It is at his high school that we are introduced to 17-year-old Andrey (Daniil Kamenskyj), who has been orphaned by the war. Nina and Andrey meet in an action-filled scene in which he breaks into the school dressed in black from head to toe in order to hang a Ukrainian flag from the roof of his school. When she decides to save him, they form a bond that will carry through to the end of the film.

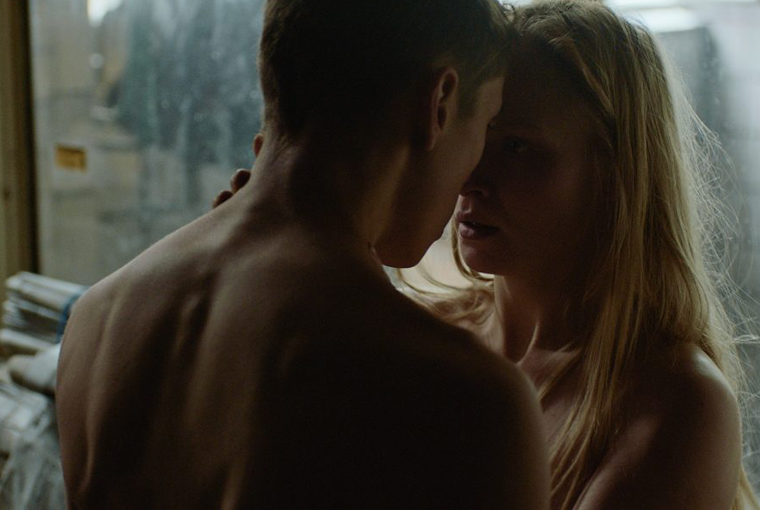

Both seething with anger yet unable to leave, Nina and Andrey share a poetic bond which is visually developed by way of props and themes. At one point, unable to explain his feeling of isolation in words, Andrey places a transparent, plastic bag over his head. Nina does the same. Their bond is also their manacle, as they see through each other’s eyes the discomfort of pretending in daily life. Their relation to a journalist who makes up extravagant propaganda about “Ukrainian terrorists” is also a unifying detail. The role of propaganda will tragically loop back to Andrey at the end of the film. When Nina does finally manage to escape Luhansk, she will see him in every student she teaches or meets in the street.

While Nina is trying her best to stay in line, Andrey is an outlier. A high-school dropout, he is living underground and part of a resistance movement whose goals are patriotic yet vague. The film gives a portrait of everyday life in the Luhansk region for those who lived there before the beginning of the conflict. At nightfall during curfew, rebel paratroopers roam the streets, shooting at people they see looming in the shadows. Meanwhile Vasyli, Nina’s partner, must negotiate crossing the tricky border almost every day. This drive is portrayed as a series of humiliations, small and big.

Things do not get better when Nina and Vasyli finally get out and move to Kyiv. Immigrants within their own country, they are treated with scorn by Ukrainians who see them as collaborators in a conflict they had no part in creating. A middle-aged man crashes purposely into their car as they drive along the road, calling them collaborationist scum. Though they are finally able to speak their own language freely, they speak it in a place where they are not welcomed by their fellow citizens.

The film’s tone is pessimistic, though some lighthearted jokes alleviate it too. It shows that while people’s best bet is clearly to leave, some people just don’t have that choice – especially teenagers and children whose parents must stay. Andrey, an orphan whose grandmother is bedridden, is clearly part of that lot. They are the ones who ultimately struggle not to be forgotten.

Leave a Comment