The Heart of Darkness of the White Patriarchy

David Jařab’s Snake Gas (Hadí plyn, 2023)

Vol. 138 (October 2023) by Martin Kudláč

The annual Karlovy Vary International Film Festival serves not only as a launchpad for Central, Eastern and South-Eastern European discoveries but also showcases the latest domestic productions. Recent editions have seen a noticeable tilt towards the newer generation of filmmakers, with the 2023 KVIFF line-up featuring a majority of Czech works from emerging local artists. A standout deviation from this trend was Snake Gas (Hadí plyn), the third fiction feature by Czech theater director David Jařab.

Amidst his commitments to numerous Czech and Slovak theater stages, Jařab made his cinematic debut in 2004 with Vaterland – A Hunting Logbook (Vaterland – Lovecký deník), an adventure thriller infused with elements of black comedy that premiered at the International Film Festival Rotterdam. Set in an ambiguously defined country within a decaying manor, the story delves into the Czadsky family’s exploration of their lineage after an era reminiscent of Communism. They are introduced by the aging caretaker to a unique hunting tradition where both the quarry and the means are notably unconventional.

Drawing inspiration from the stylistic nuances of Pavel Juráček and evoking the surrealistic motifs associated with Jan Švankmajer and Louis Buñuel, the film melds elements of fantasy, horror, and detective genre. This approach persisted in the director´s follow-up Head-Hands-Heart (Hlava-ruce-srdce, 2010). Set against the backdrop of 1914 Prague, David Jařab’s work intertwines surreal visuals with historical events, shaping a narrative that mirrors a society upended by unpredictable forces. Incorporating distinct motifs, such as cockerel breeding and a domesticated lion, Jařab crafts a symbolic depiction of a faltering world, spotlighting a woman’s fortitude in the midst of turmoil.

Snake Gas is Jařab’s third fiction feature, representing the most ambitious effort in his filmography to date. The director took inspiration from Joseph Conrad’s renowned 1899 novella, The Heart of Darkness. While this narrative has seen several big-screen adaptations, Francis Ford Coppola’s 1978 Apocalypse Now being among the most notorious, Jařab offers a contemporary take, adjusting the tale to resonate with local nuances and ensuring its relevance to the region. He describes the film as a journey into the “shadowy side of the European soul”.

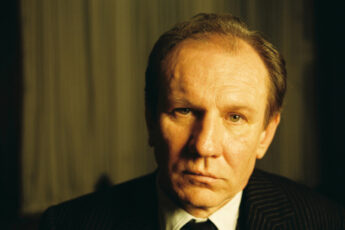

However, Snake Gas is not Jařab’s first The Heart of Darkness rodeo. He previously adapted the novel for the theater stage in 2011, featuring Stanislav Majer in the pivotal role. Majer reprises his role for the cinematic adaptation as Robert Klein, a man who leaves his partner in France to journey to Prague in search of his estranged half-brother Emanuel Klein (portrayed by Václav Vašák). Despite having met Emanuel only twice before, and with ambiguous accounts from Emanuel’s business associates, Robert remains determined to reconnect with his elusive kin somewhere in the Balkans.

Before delving into the so-called “European wilderness”, Robert encounters a Japanese firm engaged in eel capture in the area where his half-brother is supposed to be residing. Concurrently, he comes across an American entity involved in unsanctioned mineral exploration. Despite these encounters, Robert’s understanding remains unchanged. His half-brother continues to be an enigma, and the activities transpiring in the region maintain their opaque nature.

In keeping with local literary tradition, the unsuspecting protagonist delves into the unfamiliar, evoking Kafkaesque undertones, uncertain of what awaits him at the journey’s end. Jařab employs the elusive half-brother as a narrative device, presenting him as the cipher at the end of a metaphorical labyrinth. Mere mention of the half-brother’s name induces reactions of respect or apprehension in locals, amplifying the intrigue surrounding the missing sibling. As is often the case in narratives of this nature, and reminiscent of Heart of Darkness, it is the journey, rather than the endpoint, that holds significance.

The film adopts an internationalist veneer, with a Czech protagonist journeying from France into the Balkans (a significant portion of the film was shot in neighboring Slovakia). This landscape sees both Japanese and American entities demonstrate their business interests. Rather than portraying a simple cultural clash, the film delves into themes of neo-colonization in the context of late capitalism. Additionally, the narrative gains depth with the presence of Africans settled in Central Europe, adding layers to the discourse on Europe’s migration issues and colonialist inclinations.

A considerable part of the film unfolds as a fluvial road movie taking the viewer through the expansive wilds of Central Europe. Jařab crafts scenes with cryptic dialogs, ambiguous references, and veiled situations, deepening the symbolism of the geographical and psychological voyage. The search for the half-brother gradually transforms into an introspective exploration of the protagonist’s own identity, which is intertwined with the social dimensions of colonialism and xenophobia.

Snake Gas works better as a psychological mystery drama, placing the protagonist amidst numerous moral and ethical dilemmas. Oleg Mutu’s cinematography (known from 4 Months, 3 Weeks & 2 Days and The Death of Mr. Lăzărescu) accentuates the allure and challenges of unexplored realms, drawing the protagonist into its depths. As the story unfolds, Jařab lets the narrative flex, allowing the conventions of psychological drama to intermingle with touches of surrealism, bordering on delusional realism. The once-composed Robert descends into a state of delirium, unraveling his previously ordered world.

The film’s tense atmosphere ebbs in the final act during Robert’s long-anticipated encounter. The enigmatic ambiance dissipates as Jařab shifts to a more theatrical approach, marked by extensive dialog and philosophical exposition. The narrative leans heavily on open and thinly veiled political and philosophical statements that border on preaching, which redirects the film’s trajectory. Though the abundant dialog can be attributed to the “enlightenment” induced by the wilderness, the narrative might have benefited from a more restrained display demonstrated in the previous two thirds of the film.

Snake Gas presents a mosaic of ideas, which some might perceive as elusive, disjointed, or unresolved. As Jařab delves into the Central European psyche, certain universal themes and motifs emerge more prominently than others. Particularly in this quasi-existential drama, issues of gender and identity rise to the fore. The film chronicles the journey of a privileged white man: from the opening image of him poised in a white suit on a French quay, surrounded by luxurious private yachts, to a later scene where he trudges through marshlands, disheveled and slightly unhinged, as the suave facade crumbles.

Robert Klein confronts his more primal tendencies, revealing his perspectives on exploitation, a predominant theme of the film, and sexuality, a motif that, while fleeting, still garners attention. Within these contours, Jařab addresses the influence of the patriarchy on contemporary conditions, establishing it as a salient socio-political and psychological concern amidst the myriad of issues paraded in the film.

Jařab’s third film may elicit divided opinions due to its experimental approach, which could alienate some viewers. Nevertheless, he avoids the kitsch the Heart of Darkness material might engender in the hands of less experienced filmmakers. Though the final act tends toward excess in a faux crescendoing denouement, and the portrayed madness feels more theatrical than raw, it does resonate with the theme of patriarchy and the accompanying motif of male delusions of grandeur.

In the realm of Czech cinema, recent offerings from the youngest generation of filmmakers are helping to diversify the previously uniform landscape, as evidenced by the Czech slate at the 57th edition of the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival. Films such as Brutal Heat (Brutální vedro, 2023), A Sensitive Person (Citilivý člověk, 2023), and We Have Never Been Modern (Úsvit, 2023) reflect this shift. A Sensitive Person, while sharing some thematic similarities with Snake Gas, sees its director, Tomáš Klein, embracing an Eastern European take on the aesthetics of the grotesque and carnivalesque, even if it did divide audiences. Jařab, already established in his filmmaking career, appears to be aligning with this emerging generation, pushing the boundaries of local cinema.

The project benefits from the expertise of veteran Czech producer Viktor Schwarcz, who consistently shows commitment to films that, while not necessarily destined for box office success, introduce much-needed diversity to the local cinema landscape. Schwarcz’s collaboration with Jařab isn’t new; he produced Jařab’s debut, his sophomore feature, and his documentary on Czech surrealist luminary Vratislav Effenberger. Schwarcz’s diverse portfolio includes an adaptation of Philip Roth’s The Prague Orgy (Pražské orgie, 2019) as well as unique domestic films like Věra Chytilová’s nudist meta-narrative tragicomedy Ban from Paradise (Vyhnání z ráje, 2001) and one of the most eccentric works of recent years, Cook F**k Kill (Žáby bez jazyka, 2019) by Slovak director Mira Fornay.

Snake Gas and Cook F**k Kill share thematic parallels. Both explore male protagonists, their identities, and circumstances deeply intertwined with gender and the patriarchy. While Fornay presents an experimental narrative set in an urban environment, Jařab takes audiences on a mystical odyssey through marshlands and forests. Fornay’s approach leans towards avant-garde expressivity, whereas Jařab draws from established storytelling traditions, resulting in a more restrained use of symbolism compared to Fornay.

Both films stand apart from the traditional mold of local cinema. Fornay’s work clearly identifies its Central European setting through recognizable brutalist apartment blocks and rural landscapes. Conversely, Jařab’s narrative conceals exact locations, transporting audiences from France to the Balkans. Snake Gas projects a more international aura, even within its budgetary limitations. This sense of global diversity is further accentuated by the deliberate intermingling of various nations and continents within the narrative, ultimately forming a glocal oeuvre.

Snake Gas emerges as an exploration of identity, patriarchy, and cultural intersectionality. Anchored in the Central European cinematic tradition, the film takes audiences on an evocative journey that blurs geographical boundaries while juxtaposing modernity against nature’s wild expanse. While its experimental approach may not resonate with everyone, Jařab’s blending of psychological drama and mysticism challenges conventional storytelling. In an era where global cinema seeks to redefine its narrative structures, Snake Gas contributes a distinct voice from within Czech cinema.

Leave a Comment