Is there any Eros in the World of Thanatos?

Discovering Evgeny Yufit’s Late Photography (2013-14)

Vol. 109 (November 2020) by Anzhelika Artyukh

Evgeny Yufit (1961-2016) was one of the most radical figures in the post-Soviet art scene. In the last years of his life, Yufit was not very keen on talking about Necrorealism, the movement he had established in the early 1980s in Leningrad; however, in terms of subject matter and aesthetics, his late work is naturally associated with Necrorealism and its various participants, from artists to philosophers. Yufit was an artist of many talents; he made films, painted and was an eager photographer. All of Yufit’s works reflect his exploration of the liminal space between life and death, the realm of what Alexei Yurchak calls exotopy or outwardness (vnenachodimost’), an alternative form of life reminiscent of Giorgio Agamben’s concept of naked life.

In Yufit’s system of coordinates, the idea of the outside-subject (vnesubekt) emerges. It is quite similar to what the Necrorealists called the non-body or non-corpse (netrup); this form of subjectivity not only reveals the ambivalence of the living and the dead, but also refers to a state of “pure idiocy”, a certain way of reacting to the boredom preceding the collapse of the Soviet system. By exposing both the inorganic within the organic, and the organic within the inorganic, the non-corpse became the embodiment of Freud’s notion of the uncanny. In its own way, the non-corpse also promoted homoeroticism as an alternative form of resistance against the taboo of homosexuality, which was reinforced during Soviet times by means of article 121 (a criminal clause penalizing sexual relations between men that was abolished as late as 1993). In Necrorealistic cinema, homoeroticism is not only expressed in the way the men stroke and cruelly slash each other, but also in the noticeable prevalence of male naked bodies on screen, as a metaphor of the patriarchy.

As Alexey Yurchak has noted, the non-corpse can be considered Necrorealism’s particular contribution to the universal search for so-called in-between subjects (promezhutochnye subekty): the living dead, zombies, cyborgs, vampires, aliens, mutants. While Necrorealism’s explorations were a departure from the complete taboo on the political dimension of Soviet everyday life, they could not escape politics as biopower. Yufit’s focus was on the world of men. He dealt with enhanced masculinity through black humor and the grotesque. Yufit placed sailors and other seasoned men in situations inspired by Eduard von Hoffmann’s Atlas of Forensic Medicine; by performing various suicidal and sadomasochist acts, these men looked both funny and scary, and their actions expressed a total lack of rational motivation, logic and reason.

However, taking a closer look at the characters of his feature films, from Daddy, Father Frost is Dead (Papa, umer Ded Moroz, 1991) to Bipedalism (Priamochozhdenie, 2005), we can note that Yufit constantly deals with two types of protagonists: artists and scientists. Necrorealism’s focus lies not only on experimenting with reverse evolution, which is expressed in images of disaster and decay, but also in its tragic view on the discovery of knowledge as a journey into other, alternative, and fantastic realities of domestic boredom, yet ultimately descending into the image of the Odyssey. Yufit’s feature films demonstrate that his work was influenced by German expressionism, Dada and surrealism, as well as by American science fiction of the 50s, which the artist was able to discover when he divided his time between Russia and the United States from the mid-1990s onwards.

Yufit’s final film Bipedalism (2005), supported by the Hubert Bals Fund, was produced by Igor Kalenov and Sergey Selyanov. Only one single copy was distributed in Russia and brought in $3000 according to kino-data.ru. Despite the fact that in the year of Bipedalism’s release the Rotterdam Film Festival arranged a retrospective of Yufit’s oeuvre, the producer was not particularly engaged in further promoting Bipedalism outside of Russia. My attempt to organize together with the Swedish, Riga-based producer Thom Palmer a co-production of The Dream of a Ridiculous Man (Son smeshnogo cheloveka), based on a script by Russian language Estonian writer Andrey Ivanov, failed due to the political situation in Ukraine. The script was written with two people in mind: Yufit, and Denis Solovyov-Friedman, an actor, linguist and interpreter, who had been living in Tartu for a long time. Solovyov-Friedman had begun his creative work in the late 80s at Timur Novikov’s New Academy of Fine Arts. After emigrating to Israel in the early 90s, Solovyov-Friedman returned to Russia in the 2010s, with the expectation to realize the film with Yufit.

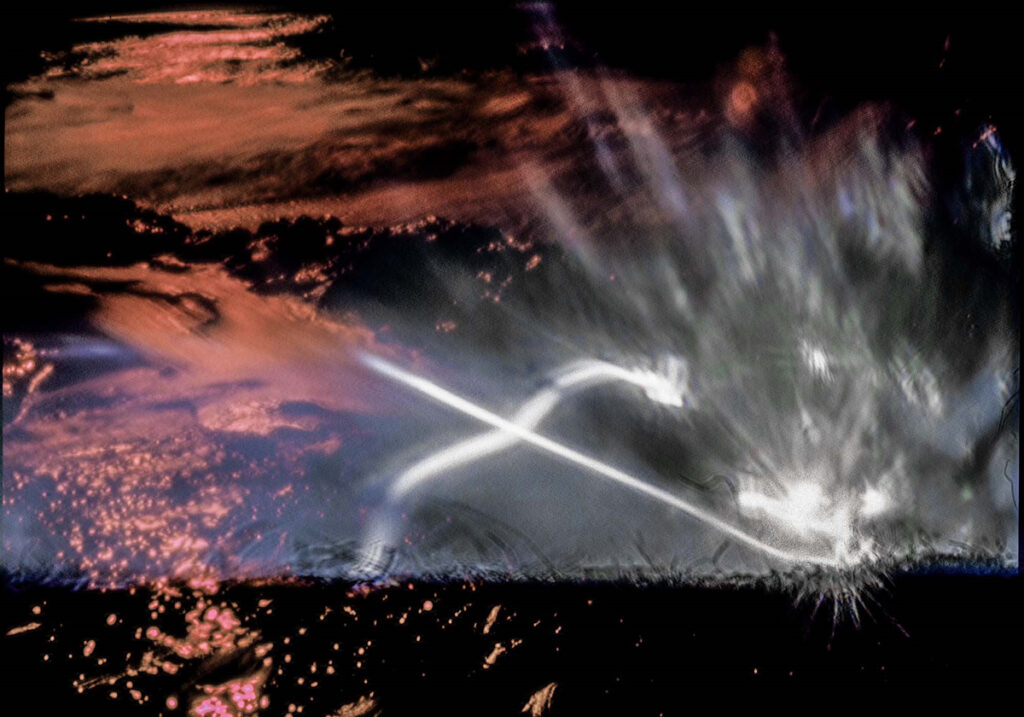

For many years, Evgeny Yufit was only able to work in the field of photography and painting. His last two series of photographs are dated between 2013 and 2014. The first series was a particularly valuable collaboration with Solovyov-Friedman; the second series, Silent Horizon, consists of photographic landscapes and uses the technique of pinhole photography. In these last works, Yufit appears as both artist and scientist in one person; echoing one of Andy Warhol’s statements about himself, the artist is here “working towards death”. These two series, which are being shown here together for the first time outside of Russia, allow us to think about the male perspective on possible personalities and images of death. Both are pictured as being intertwined with the vital forces of nature on the one hand, and the spontaneous unpredictability of sexuality on the other. This view is created not only by the choice of perspective and angle, but also by its technology and staging, a complex interaction of optics, the actor’s make-up, the frame composition, the image and background processing, the colors, and the choice of the moment that is captured through the lens. By tracing the mutual tensions between Thanatos and Eros, Yufit’s latest experiments are a unique invasion into the territory of queer culture (taking also into account his collaborator Solovyov-Friedman’s bisexuality). It seems that in these magical works, Yufit manages to capture the border zones of various transgressive transitions.

– Anzhelika Artyukh

courtesy of Timothy Yufit

courtesy of Timothy Yufit

courtesy of Timothy Yufit

courtesy of Timothy Yufit

courtesy of Timothy Yufit

courtesy of Timothy Yufit

courtesy of Timothy Yufit

courtesy of Timothy Yufit

courtesy of Timothy Yufit

Credits

Photographs: Evgeny Yufit

Introduction: Anzhelika Artyukh

Translation: Isabel Jacobs

Title Picture: Evgeny Yufit, Autumn, 2013

Copyright: All images are the courtesy of Timothy Yufit

Leave a Comment