Don’t Call Me By Your Name

Elmar Imanov’s End of Season (Ende der Saison, 2019)

Vol. 92 (February 2019) by Rohan Crickmar

End of Season is a German-Azerbaijani-Georgian co-production and debut feature from Elmar Imanov. Shot on location in Azerbaijan, with an Azerbaijani cast and an international crew, it is another entry in the perennially cliched dramatic sub-genre of family in crisis films. However, there is little cliched about Imanov’s screenplay (co-written with Anar Imanov), which is a scathing, blackly comic and boldly subversive rally against sentimentalism. It is also impossible to look at the film’s penultimate shot without reading it as a masterful and mocking riposte to the privileged solipsistic moroseness of that end credit shot in Luca Guadagnino’s heavily celebrated sun-soaked romance Call Me By Your Name.

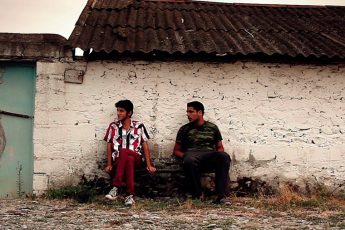

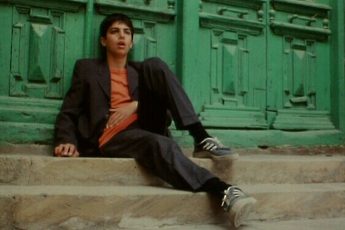

Elmar Imanov is a filmmaker living and working in Germany where he also studied film at the Internationale Filmschule Köln, but End of Season is entirely shot in Baku, his home city and the Azerbaijani capital. As such End of Season is part of a recent trend of European co-productions, in which a filmmaker trained within the EU heartlands, returns to the peripheral Europe that they have left behind (Elene Naveriani, Ena Sendijarević, Paweł Pawlikowski, to name a few). It revolves around a family of three: Machmud (a simultaneously cherubic and demonic son), Fidan (his restless and suffocated mother) and Samir (a broken father who simply wants to be alone). Imanov deliberately introduces this family unit obliquely, so that the audience cannot necessarily navigate their relationship to one another. Machmud (Mir-Mövsüm Mirzazade) is initially shown as a boyish presence messing around with his breakfast, but quickly reveals a tough, hustling adult exterior, flagrantly suggesting to one of many girlfriends, that he could use her help to open a brothel. Fidan (Zulfiyye Gurbanova) meanwhile has obviously been a younger mother and her early interactions with her son deliberately blur the line between familial and sexual relations. Like Machmud, Fidan is someone who leads a dual existence, claustrophobic and stifling in the domestic sphere, but increasingly adventurous out in public, where she has a professional career as a doctor. Meanwhile Samir (Rasim Jafarov) is such a lackluster and negative presence in his own home that it would be difficult to discern any kind of father-son bond between himself and Machmud, let alone a loving relationship with Fidan.

The one tie that binds the family together is how little each of them cares to be in the other’s company. The compacted hatred that kicks out of nearly every line of dialogue leaves little doubt that these are people in a purgatorial place in life. A desire to find a separate and personal space outwith the family unit, is actually the truly destructive impulse, leading each character into far worse predicaments than they inhabited at the beginning of the film. It is as if Imanov is reflecting the tensions between the private and the communal within society. The more comfortably middle-class a person becomes, the more likely they are to regard themselves as an individual first and foremost. The micro-community of the family cannot possibly survive such a sense of entitlement to increased sovereignty. This breakdown in community is further reinforced by the isolation of the family’s apartment within a tower-block of similar apartments. Rarely does the film show neighborly relations, even though the impressive opening drone sequence details the dense concentration of residences in the family’s neighborhood.

The character of Machmud is particularly cutthroat in his greed and self-interest. He wastes no time demanding what he wants from people and expects them to fall in line with his every whim. In one of the best scenes of the film Machmud is shown to have met his match when looking to rent a flat. The middle-aged man who is showing him the flat clearly has no intention of getting anything less than what he wants from this particular transaction. Despite Machmud’s attempts to mollify him, the man insists on his terms: a high rent, little or no freedom and absolutely no chance of renovations or modernization. What their conversation most strikingly hints at is the external pressures upon this man from his own son, who is desperate for his father to rent out the flat. Self-interest breeds self-interest.

The film is at its strongest when it is being boldly confrontational. Counter to the way in which the family members are shown to be separately pursuing their own ideas of freedom, they are very clearly related as a family in the ways in which they verbally joust with one another. Machmud is shown to have an unvarnished way of cutting to the chase. Fidan by comparison almost never finds a direct route to telling those around her how she feels or what she wants. Her desires are verbally displaced into faux concerns with Samir’s inertia or Machmud’s selfishness. This makes her direct confession of marital infidelity toward the end of the film all the more powerful, for it is the first time in the film that she gets expressly to the point. That scene becomes pure comedy thanks to Samir’s uncomprehending disbelief. Samir is so used to be verbally bullied and undermined by his son, that when confronted with an unbelievable truth, he simply cannot bring himself to respond.

Intriguingly, it seems that Elmar Imanov had laid the ground work for a return to Azerbaijan when shooting a short film called The Swing and the Coffin Maker in 2012. In an interview around this period he claimed his first feature would be a German production, but talks extensively of how he had awoken to the possibilities of Baku and his home country.1 Working with an international crew in Baku, Imanov seems to have found the perfect in-between space to produce great drama. It will have to be seen whether his commitment to Azerbaijani cinema survives the undoubted critical acclaim that will gather behind this neat little drama of dissatisfaction.

Leave a Comment