Periphery and Center, Nationalism and Patriotism

Simona Kostova’s Thirty (Dreissig, 2018) & Ena Sendijarević’s Take Me Somewhere Nice (2019)

Vol. 92 (February 2019) by Rohan Crickmar

Two films that received their world premieres at IFFR 2019 were made by female filmmakers of Balkan backgrounds, both of whom had trained in Central European film schools and made their first features there. Simona Kostova’s Thirty is a genuinely inventive feature debut, shot on a shoestring, as it follows a bunch of Neukölln residents on the verge of their thirties, navigating a long dark night of the soul. Ena Sendijarević’s Take Me Somewhere Nice is the latest rung on the ladder for a Dutch-Bosnian filmmaker that the Netherlands film industry seems to be relatively excited about. Sendijarević’s film focuses on Alma (Sara Luna Zorić), a Bosnian girl raised in the Netherlands who decides to return to Bosnia to see her estranged and sickly father. Alienated in her adopted home, Alma soon finds a different kind of alienation in the country of her birth. Both of these filmmakers are working around the edges of their own biographies, testing out the center from the periphery, or, in the case of Sendijarević, working at the distinction between the nationalist and the patriotic.

Thirty opens with a striking long-take that introduces us to one of the principal characters of the film Ove (Övünc Güvenisik), who will turn thirty over the course of the film’s 24 hour narrative structure. Ove cannot stir himself from bed, eventually he gets up, the camera gracefully pulling out of its initial close-up to reveal a wider shot of the bedroom. Ove then restlessly wanders around the edges of his bedroom, looking for his phone, finding some cigarettes, pulling on some clothes. Never once does he take the center of the shot, until he opens and closes a window. Even this drift into the center is something like a tentative hop in and back out again. The audience doesn’t know it yet, but the very core of the film has been crafted in microcosm in this single shot.

The characters that Kostova populates her film with are inhabitants of the rapidly gentrifying Neukölln district in South-East Berlin. This is a location in the very throws of being moved from periphery to center, as the neighborhood goes from gritty working class suburb to hipster hangout. The core group of friends identify strongly with the neighborhood even if their working lives may suggest that they are part of the gentrification process. Ove, whose birthday the friends are celebrating, is a writer struggling to write, and gripped by an existential dread of what his thirties mean for him. Raha (Raha Emami Khansari) and Pascal (Pascal Houdus) are a couple who have quit being a couple even if at least one of them isn’t sure why. Kara (Kara Schröder) is an intense bundle of neuroses and anxieties that are constantly deflected through rambling monologues about everyone else’s problems. The most affable of the core group of friends is Henner (Henner Borchers), who seems to be a happy-go-lucky guy without much care for plans and structure. Yet it is Henner who has perhaps the most striking breakdown of the entire film, suddenly gripped by an inner dread that plays out like a drug-fueled flashback. Inertia and avoidance lie in every moment of the day for these friends, which is what gives the film its dynamic narrative momentum. The night cannot end, they have to move onwards, be taken by the moment, for fear that in standing still they will eventually be caught by their worst enemies, themselves.

Kostova is an older filmmaker with a strong creative relationship with her production partner Ceylan Ataman-Checa, also a director. Their film has the feel and energy of something that had to be made and damn the consequences. Costing just 5,000 Euros and having been shot over only eight days with a tiny crew, the film should be a rough and ready affair, and yet what stands out most clearly is the absolute precision and control brought to so many of the film’s sequences. From the careful choreography of the camerawork, that moves fluidly from close-up to long shot without cutting, through to the rhythmic ebb and flow of the edit over the course of the night, or the impressive control of lighting in the two striking club sequences, this is a film that constantly feels as if it has achieved far more than the modesty of its source materials. Its focus upon Neukölln as the backdrop for the group’s nocturnal odyssey also seems to come from an outsider’s insider perspective, as if Kostova’s migrant background has found a place on the periphery within Berlin, from which vantage point the city lies more clearly and transparently open.

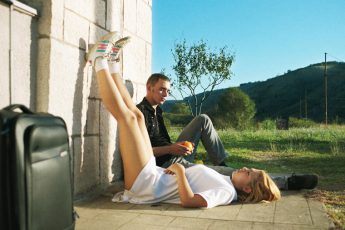

By comparison Ena Sendijarević’s Take Me Somewhere Nice seems as desperate to get away from the Netherlands as its central protagonist Alma. Whereas Kostova finds a periphery within the center from which to situate her outsider’s eye, Sendijarević opens up the vast nowhere space that children of migrants inhabit, feeling alienated from the country they have grown up in, but being an absolute outsider when returning to the country of their birth. What we see of the Netherlands in the opening sequences of the film are very suburban, safe, uncomplicated spaces. Alma isn’t coming from a place of privilege, but she is coming from a place of comfort, which is swiftly contrasted with her new reality on her return to Bosnia. Her older cousin Emir picks her up from the station and Alma immediately comments upon the datedness of his car, the first of many comments that needle him.

Alma clearly has expected some degree of special treatment from her Bosnian family, yet her cousin Emir seems almost entirely disinterested in her, if not actively irritated by her presence. Left in a flat that has nothing but time available in it, Alma is itching to get down to see her ailing father, but Emir (Ernad Prnjavorac) isn’t willing to take her. When Alma tries to get to her father’s on her own, she finds travelling far more difficult than she would have imagined. Purchasing a bus ticket becomes an exercise in stubbornness. The bus journey itself is spent uncomfortably straddling the stairs at the center of the bus. Her journey is interrupted when she misses getting back on the bus at a rest stop. Every step of the way in Bosnia she is reminded of the fact that she isn’t from there, even if her language skills enable her to give the impression she is. During one difficult conversation with Emir, her cousin talks about his own relationship to his country. His is not a nationalist sentiment, he doesn’t hate other places from a position of haughty superiority, he simply is at home in Bosnia – this he talks of as patriotism. What Sendijarević smartly does within this scene is shift the prejudices that normally congregate around a nationalist narrative on to the returning migrant’s supposedly more cosmopolitan attitudes. It is Alma that is shown, consciously or not, to have a certain negative and superior attitude toward Bosnia, even if she would never dare identify herself with Dutch nationalism. Thus, when the periphery moves toward the center can it ever really return to the periphery?

Sendijarević’s film benefits from a production apparatus that simply wasn’t there for Kostova within her adopted German context. Sendijarević has been supported through her shorts film career by the main funding agencies of the Dutch film industry, with the IFFR building a relationship with her as a promising young voice coming from an interesting place within the domestic film circuit. Whereas Kostova’s producer was a first-timer like Kostova, Sendijarević has the production support of the likes of Sander Van Meurs, a Dutch film and television industry figure with 20 years of experience, as well as the full backing of VPRO, one of the major Dutch public broadcasters and a frequent co-production partner with the likes of Arte and the BBC. It is interesting to consider what this reflects of the two film industries, even taking into consideration Kostova’s clear preference for a kind of DIY cinema that is always going to be exiled to the periphery. Both filmmakers come from the Balkans, both have been educated and trained through film schools within Central Europe, both are female filmmakers working on their first feature, and these first features are both slyly political despite at first appearing to have little obvious interest in political discourse. The difference here is in terms of how the respective industries have handled and situated these talents. Thirty gives the impression of having caught the German film industry by surprise, having been crafted and created well outside of the domestic production infrastructures that would normally be available to first time feature filmmakers. By comparison, Take Me Somewhere Nice seems to have been carefully developed and promoted within the very heart of those domestic production infrastructures. Periphery talking to the center, center reporting back to the periphery: welcome to the 21st century European film landscape.

Leave a Comment