Silent Clash

Elvin Adigozel and Ru Hasanov’s Chameleon (Buqälämun, 2013)

Vol. 49 (January 2015) by Moritz Pfeifer

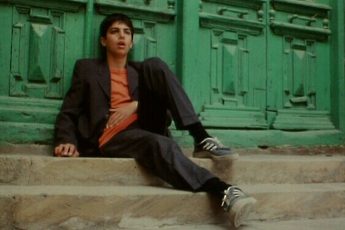

This film tells the story of three young men and their unlikely encounter around the purchase of a house in the forsaken district of Goychay, located pretty much in the middle of Azerbaidjan (“in the middle of nowhere”, as one lady in the film puts it). Nijat inherited the house from his grandfather and wants to sell it after having spent some time abroad. From his cosmopolitan dress-code – red jeans, fashionable sunglasses, and a tucked-out shirt – it becomes clear that it makes little sense for him to settle down in the rural environment of his ancestors. Although he never reveals why he is selling the house, he admits not having a lot of money and that he is the owner of a patent and a company. The buyer of the house is Ali, a careerist project manager for a construction company. Like Nijat, his outfit is composed of sunglasses, jeans, and a shirt. But with his buzz cut, tucked-in, clean white shirt, his black trousers and American-Gangster-type sunglasses, he comes across as a mafia-film stereotype, an image he consciously tries to represent in the snobbish way he speaks to his employees. Lastly there is Rafi, who is a simple village boy, working from time to time as a plumber. Before Nijat can sell his house, he has to fix the sewage system and so a friend of Nijat who helps him sell the property, convinces Rafi to do the job. Compared to Nijat and Ali, Rafi represents the typical village idiot who will do everything for a bit of cash. With his dirty, unfashionable clothes, he constantly speaks about money, panicking whether he will get payed at all.

The two directors nicely show the differences of education, class, and culture of the three protagonists. Typical for this almost anthropological kind of study is to reveal the clash in small, everyday gestures. Take the eating-habits of the three men for instance. At the bottom of the food-chain is Rafi who is constantly hungry and would probably eat everything. Then comes Nijat who reluctantly chews on a cucumber at his friend’s house a couple of scenes later. Towards the end of the film, after the house is sold, he enjoys a burger with fries in a fast food joint, his globalized version of a feast. Although we never see Ali eating, his tight-fitting shirt reveals the rudiments of a potbelly, which, if one takes a look at his superiors, seems to get bigger according to the position everyone holds in the company. One can see that he eats well and plenty.

In spite of obvious class differences, the three men are connected in their search for prosperity. Even poor Rafi mocks one of his fellow villages when he sees him on a bike instead of a car, as if owning a car is the ultimate symbol of adulthood. Although the dreams of wealth of the three men come in different versions, a deeply materialistic worldview unites them. It is also what separates them from the previous generation. In fact, the real difference lies in the relationships they have with those who are twice their age. For Nijat, it is the rural life of his forefathers. Their ideas of a modest but comfortable life stand against his cosmopolitan ambitions. Ali quarrels with the values of his older superior. In one scene, his superior tells Ali that he did not sign a deal to construct a highway that would have gone through the cemetery where his father is buried. He simply had to call some friends in the local administration to stop the project, a decision that was backed by the community which also preferred not to trade in hills and graveyard for a highway. Although Ali does not reply to his superior’s morality tale, it is clear that he would have acted differently. Unlike his superior, Ali’s way of business is profit-based. Rafi’s male counterpart is an older villager, the one who helped Nijat sell the house and convinced Rafi to do the plumbing job. Here as well, business is first and foremost a matter of favoritism. Although Rafi is not payed much (three or four Manat, which equals roughly the same amount in Euro), it doesn’t seem like an unfair deal. The older man simply does not have more money to give. He also asks a woman to clean the house for free, which does not seem awkward to the woman. In short, the traditional economy of the older generation is based on an exchange of services for money and is not driven by profit-maximization. It is more like a pre-capitalist economy where labor is understood in terms of the personal relationship between a master and those working for him.

These highly complex mechanisms of social change almost remain unnoticed as the film slowly unfolds and connects its multiple story lines. But beneath its minimalist plot and forsaken setting, the two directors skillfully achieve to unmask a conflict-ridden clash between an increasingly globalized, capitalist youth and an older generation which tries to preserve local customs of personal favoritism. Chameleon‘s extremist subtlety makes us aware that historical change is often hidden from those living it. The directors’ own take on the conflict can perhaps best be described as nostalgic, and gets revealed via 8mm footage of Nijat’s youth, remnants of a more innocent and carefree childhood. With its astute cultural and historical observations, this modest film definitely deserves more attention.

Leave a Comment