Disappearing Generations

Rodion Ismailov’s My Kith and Kin (Doğma ocaq, 2012)

Vol. 50 (February 2015) by Moritz Pfeifer

This movie bares a striking resemblance to another Azerbaijani documentary I discuss this month. In He Was a Giant with Brown Eyes, Sabina, who grew up with her mother in Switzerland, returns to Baku looking for her father and sister. In My Kith and Kin, Moscow-born Lolita comes back to Azerbaijan with her father to visit their relatives for the first time. Both films are about adolescent women of Azerbaijani origin who grew up in a foreign country and come to Azerbaijan in search of their origins and family history. Instead of succumbing to clichés of the clash-of-civilizations type, these films sensibly portray changing values and customs in family structures. In both films, the girls’ parents are divorced while their grandparents live in tight-knit kin groups, with three or more generations sharing the same house or village. The girls and their parents represent a different, cosmopolitan life, which is more individualistic and less traditional. In these films, generations clash, not cultures.

Another remarkable similarity between My Kith and Kin and Giant is their docu-fiction style of filmmaking. Both films are documentaries but don’t care much for traditional documentary aesthetics. They look more like classic art-house features dramatizing their stories with music, close-ups, and a more or less invisible filmmaker (only very few characters quickly glance into the lens and thus reveal that they are not “acting”). While some scenes, such as when Lolita meets her family for the first time, are clearly staged (or did the director arrive before his protagonist?), this intimate type of filmmaking matches the personal story the director wants to tell.

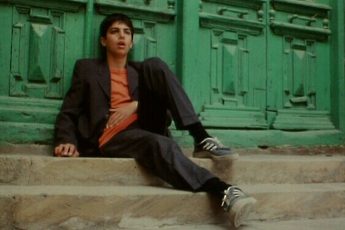

Although Lolita is extremely polite and thankful for her family’s good will, it is obvious that they don’t have a lot in common. This is already conveyed in the first two shots of the film where Lolita can be seen in a theatrical dance performance and shortly after that announcing to her father on the phone that she won the first prize of a writing contest. It would have been interesting if the director would have given a more explicit comparison to these competitive games, though her cousins in Azerbaijan are shown to have less institutionalized forms of passing their free time such as swimming in a nearby river or helping friends with making food.

My Kith and Kin earnestly conveys the sense of loss a teenager may experience when she realizes that she doesn’t belong to a group. When Lolita’s family sacrifices a lamb for her on the top of a mountain, she starts crying. When her dad asks her why, she says that she feels sorry for the lamb. Perhaps she also feels guilty for the fact that she cannot appreciate their values. Here the film provides an interesting comparison. Lolita and her father bring gifts from Moscow for everyone, which provokes a moment of awkward silence as nobody in the family seems to be particularly excited about receiving clothes in colorfully wrapped plastic boxes.

My Kith and Kin, like other Azerbaijani films, feels nostalgic about a disappearing generation represented by a very traditional, family-based life style. At the end of the movie, Lolita’s grandmother shows her granddaughter pictures from her youth and ancestors going back to Lolita’s grandmother’s grandmother. Looking at the people, their clothes and habitat, one gets the feeling that not much has changed. The film ends with real-life portraits of the families living in the village. These portraits, too, resemble the pictures in the grandmother’s photo album. Who knows for how much longer.

Leave a Comment