Dances of Procedure

Goran Škofić’s Sector (2015) & Elena Artemenko’s Soft Power (2016)

Vol. 70 (December 2016) by Rohan Crickmar

The routine can sometimes be made beguiling, and some filmmakers are able to find a curious beauty in procedure. These two short films, one by Russian artist Elena Artemenko and the other by Croatian artist Goran Škofić, examine conflicting ideas of community in a playful and carefully choreographed fashion. Both use interesting camera placement and subtle digital manipulation to transform mundane surroundings into exquisite cinematic sculptures. Their work demonstrates how aesthetic commonalities can freely emerge within different artistic milieus, and how these commonalities are deployed for entirely divergent means.

Škofić, born in Pula in 1979, has worked with photography, video collage, spatial installations, recorded performance and sound design. His filmmaking career stretches back to 2001 and the creepily unsettling and atmospheric short film House of Dolls. Within Croatia he was the recipient of the Radoslav Putar Award in 2009, for the best young Croatian artist under 35. Artemenko hails from Krasnodar in the Kuban region of Russia. Born in 1988, she is, in effect, a generation younger than Škofić. Her background is in journalism and multimedia art, the former almost certainly informing her quietly combative politics of resistance present in her earliest video work Political make-up (2010). She has twice been nominated for the Kandinsky Prize for the best young Russian artist.

Choreography plays a significant role in both short films, although Artemenko’s approach involves foregrounding the process of film editing as another layer of the choreographic, whereas Škofić’s film seems to be a simple single take, but is in fact discreetly edited and looped. Sector presents an aerial shot of a giant hexagonal welding platform. The film was shot entirely on location at the Mali Lošinj shipyard in Croatia during the summer of 2014. Working with the composer and sound designer Nenad Sinkauz, Škofić has put together a dance of the welders. Seven of the shipyard’s welders take to the welding platform, with their equipment and protective clothing. Carefully spaced around the perimeter of the platform, each welder uses their tools to create a light and sound display from the industrial process they have been trained to perform. Sinkauz has scored these straightforward industrial procedures that each of the welders engages in, to create the music of welding, or truly industrial music if you like.

The purity of Škofić’s film comes from its deceptively simple visual realization of this music. The looping footage and the spatial organization of the work on the platform, as well as the distance between the camera and what it observes, helps to underscore the artist’s primary concern with showing the individual engaged in a process of work, alongside others, thus developing communal bonds. It is noteworthy that with this work Škofić describes himself as following in the footsteps of those artists that worked on art projects with workers during the Communist period in Eastern Europe, as well as with similar proactive and politically-inclined work pursued by the likes of the Artist Placement Group in the UK during the 1960s and 1970s.

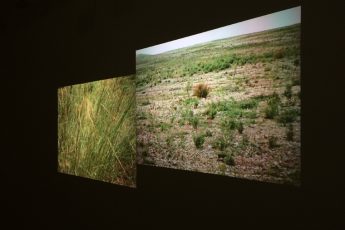

Artemenko’s film begins with a similarly distanced aerial shot, that abstracts the image of a tower-block rooftop within a busy urban area. On this rooftop a number of people carry out a series of repeated gestures and physical processes that cumulatively suggest a structure of authority, hierarchy, responsibility and the execution of force. It is not only the physical choreography that Artemenko is concerned with, but also the construction of a musical score generated from the mechanical sounds produced by each gesture or action within the wider processes. The performers upon the rooftop, at various points, seem to form themselves into two opposing groups of three. One side physically commands the other side to perform gestures and actions on cue, using a series of complementary gestures and actions. Eventually the control of one side over the other creates a final process of dominance, in which a prosthetic arm and a gun are positioned over the three figures who are dominated. This final process is revealed through a repetitious sequence of editing, that progressively atomizes the process through tighter and tighter use of close-up. The end point of the process is always a horrendous scream emanating from the mouth of one of the group of performers, until their mouth closes.

Soft Power reveals itself to be very much concerned with the cultural construction of hierarchies of power through processes of instruction. The choreography of the film makes organized force from a seeming dance of chaos, then demonstrates how this organized force dissolves back into a renewed dance of chaos until it reasserts itself through a different process of construction and a new hierarchy of power. All of this is captured in hyper-saturated colors dominated by the colors white, red and blue – a rather bald allusion.

The very act of choreographing is one of visually making sense out of apparent disorder; establishing rhythms and patterns where there may appear to be none. Both of these artists take choreography a stage further and look to find procedures that can be foregrounded through its application. Škofić’s approach is one which finds a communitarian bond in the procedures of industry, seeking out an almost nostalgic return to workers’ art. The directness and simplicity of Sector becomes complexity and atomization in Soft Power. Artemenko is using choreography to show how individuals can be divided, manipulated and overpowered. However, the logic of her choreographic process also leaves open the possibility that hierarchies of power and organized force are themselves eventually undone by the procedures that have constructed them.

Leave a Comment