Silent Year

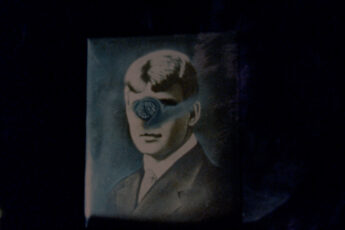

Janez Burger’s Silent Sonata (Circus Fantasticus, 2010)

Vol. 13 (January 2012) by Moritz Pfeifer

Robert Bresson’s bon mot that it was the sound film that invented silence (“Le cinéma sonore a inventé le silence”) is a theme that passed through at least three of last year’s films. First there was Skolimowski’s comeback with Essential Killing (technically from 2010 but in theatres in 2011), where an anonymous Arab is chased across Europe without ever speaking a word; then there was Michel Hazanavicius’ attempt to make a 1920s-style silent film with The Artist; and finally Janez Burger’s Silent Sonata, a film about a grieving family somewhere in a forlorn post-war Balkan country.

All of these films treat silence differently. In The Artist, silence is a historical clin d’oeil, and in Essential Killing an attempt to enhance the spectral-like character of the Arab. Although these two films lack dialogue, the absence of speech appears quite natural. Both films succeed in finding expressive substitutions – music, and gesture-based acting in The Artist; the sound of nature in Essential Killing – and these substitutions make the films speak. Silent Sonata takes on a more metaphorical approach. Here the absence of speech is only rarely counterbalanced by a different talking element, perhaps because the silence of the characters is used to symbolize speechlessness as a reflection of their traumatic past.

The film is almost entirely set around on a farm in the middle of nowhere. There are no fields, no streets, and almost no tress surrounding the house. It belongs to a father, his two children, and their mother who is shot in the beginning of the film. Soon afterwards trucks stop before the estate and the father prepares himself for defense. But the visitors turn out to be circus artists, not soldiers. Although there is no audience around except for the one family, they decide to set up their camp. Soon, their more cheerful nature seems to help the family to overcome their loss. In one scene, one of the artists goes on a bicycle ride with the teenage daughter. During the trip they come across a couple of dead soldiers lying in the sand, but instead of taking flight in shock at the sight of the decaying bodies, the boy starts decorating the corpses with flowers and sea shells, inviting the girl to join him. The ritual has an obvious cathartic effect, helping the daughter to come to terms with death.

Similar to nature in Essential Killing, the circus in Silent Sonata has the function to speak for and instead of the main characters, that is, the three family members. Thus the circus is itself largely metaphorical and some of the artist’s more supernatural performances – winning a fight against a tank for example – could be seen as evidence that they are really only the phantasmic material of the family. Indeed the whole setting of the film is so symbolic – the solitary house in a streetless landscape, the house itself with its unfathomable shafts and corridors – that one might wonder whether it has more in common with the interior of a psyche than with the open space it purports to signify.

But here the film is undecided. While it is creative in finding images connected with trauma, loss, death, and grief (although some of these – for example running water over objects from the past – do resemble well-known Tarkovskyan metaphors), these dream-like elements contradict with the realist stage direction for the characters to shut their mouths. If the circus speaks for the family, why only let them sing? Yes, the speechlessness of the family can be understood on a symbolical level, but unlike some of the more felicitous images of the film, it doesn’t say anything more. On the contrary, at times one has the feeling that the characters actually would like to speak, but that something else than their psychic condition keeps them from doing so.

Leave a Comment