Michal Hogenauer is a recent graduate from the FAMU film school in Prague. Children Watching Night Trains, his first short film, is a portrait of two lonely kids who show no respect for their pathetic parents. The teenage girl doesn’t speak, a personification of the lack of communication which makes their lives so difficult and dark. Their relationship develops, reaches its peak and then comes to a gentle ending. Picturesque and atmospheric, with long looks and little dialogue, this twenty minute film is worth watching until the end.

Tambylles, Hogenauer’s second film, is also set in a small city in the Czech Republic. Here, we find Ivan Ríha, once again as the male lead. This time he plays a nameless eighteen-year-old just returned from a center for juvenile delinquents. While the lack of communication was thematic in Children Watching Night Trains, here silence only serves to frustrate the viewer. Again, we have many close-ups of Ríha’s face, but with no context whatsoever, we cannot even really invent our own stories about what his thoughts might be.

Lengthy shots of character’s faces usually work near the end of films when we can consider the characters thoughts and emotions, the movements of their eyes revealing their inner turmoil. When one is watching a good film, this technique works well, providing quiet moments after torrents of information and emotion which permit the viewer to imagine the characters’ thoughts. When they come from a stubborn, inexpressive face with which we have no empathy, it doesn’t work so well. The lead apparently feels no guilt for killing and raping a thirteen-year-old girl.

“Tam byl les” – the title is made up of three Czech words that translate into English as “there”, “was” and “forest”. Like the film itself, the title is well-meaning but muddled, an unfortunate destiny for an interesting story. The first part is in the style of a documentary. “These days in the Czech Republic, there is a big boom of documentaries… they manipulate and lead the people in front of the camera, they pay them for their roles, but they always present these footages [sic] as the truth. I just wanted to let the audience realize that there is always a manipulator,” says Hogenauer. So the film is broken into two parts: false documentary and fiction. At the beginning, the film really seems like a typical bad television documentary- interviews with angry villagers saying that the criminal shouldn’t be allowed to return to the village, the family in the car taking the boy home, interviews with his parents…

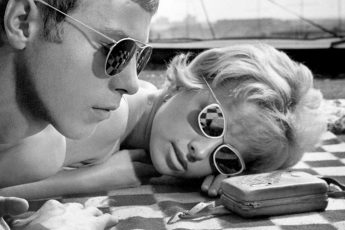

But then the documentary starts to break down. We hear the voice of the filmmaker more often, and he even takes the boy to the spot where the girl died and asks him impertinent questions while the boy, inexpressive and confused-looking as ever, stands there looking nervously. Finally, when he tries to organize a meeting between the teenager and the murdered girl’s mother, we see the filmmaker (played by Hogenauer himself) standing alone outside the bar where they were supposed to meet, a look of glee on his face as he plays back the scene to himself on his own camera. Filmmakers are thus portrayed as manipulative and abusive. This unexpected mise en abyme could have been a redeeming factor had the film finished at this point, but instead it continues with a story about the documentary maker’s role in the sabotage of the boy’s ‘recovery’. Hounded by the local villagers, he takes a flat in a neighboring village about twenty minutes away. Once there, he meets a pretty blonde girl with a wild personality, but who is stolen away by the documentary-maker in a laborious ending.

The film lasts fifty-eight minutes, much longer than the average short film, but still too short to be a feature. There is no reason a film should last any particular length of time, but this film is too underdeveloped to be a full length film. As a short film this critique of the documentary as manipulation might have been more pertinent. We can only hope that this originally promising director can get back on track and start making better short or long films.

Leave a Comment