Deadly Alphabet

Paweł Pawlikowski’s Cold War (Zimna wojna, 2018)

Vol. 92 (February 2019) by Daniil Lebedev

The latest Pawlikowski film revolves around the theme of “love as risky business”. It is the story of a handsome Polish musician and composer, Wiktor (Tomasz Kot), who just wants to live happily with his beloved Zula (Joanna Kulig), a young talented singer, but tries painstakingly to avoid getting hurt (not succeeding). The film can be summed up in the sentence: if you want love, get ready for blood.

Wiktor and Zula are sick and tired of the propagandistic Polish music ensemble they work in, and so they decide to flee to Paris. But at the last moment Zula decides not to come and Wiktor leaves on his own. He plays piano in Parisian jazz clubs and waits for her every evening. And so she comes. But only for a day: she is on tour with the ensemble. It takes Wiktor another five years to come up with the idea to go see her at a concert in Yugoslavia. But, too bad, still he doesn’t have enough guts to stay. So he returns to Paris, and after a while she comes there too, to live with him. Nothing comes out of it and after a quarrel she departs to Poland without saying goodbye. He becomes depressed, understanding that he will have to go get her this time. So he returns to Poland and is condemned to 15 years of prison for national treason. Using her connections Zula pulls him out of it, and they commit double suicide.

At first, all this coming and going in and out of Poland seems to be a metaphor that tries to provide another dimension to the Wiktor-Zula story by adding the idea of motherhood as an entity you have to suffer with to feel the sense of belonging. Thus, the images of Zula and Poland would become one in Wiktor’s endless striving for his self. But the construction, if there is one, is not convincing, and his concern for Zula seems fickle, ephemeral and surely not strong enough to justify the big change in him that makes him leave Paris for prison and torture. His imprisonment seems nothing but a desperate cry of the director who needed to end the bad trip where his heroes continue taking trains between Poland and Paris again and again. And the scene of the double suicide is where this cry becomes hysterical.

But there was no way back. What can you do after turning, with the wave of a hand, a middling pianist into a martyr? The film is ruined – but you still can win some mild hearts. It seems that this last scene, where Wiktor and Zula sit on a bench and take pills, is made for journalists to call it poetic. As if there was something inherently poetic in the mere proposition “lovers die in each others’ arms”. Like the “THE END” title, it is a good way to wrap up just about anything you want: from TV commercials to Oscar-nominated films. It is such a pure, washed-out sign, that it doesn’t even have to make sense. And Pawlikowski seems to love such signs.

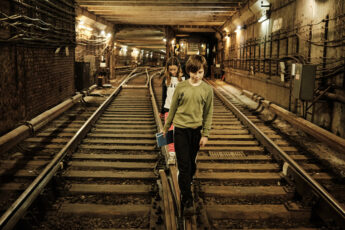

It is clear that Pawlikowski’s images are constructed to produce simple pleasures. Take any shot from either Ida or Cold War and you’ll get yourself a poster ready to hang in some artsy café. And being artsy means precisely being able to provide pleasures that mimic artistic joy. To put it otherwise, pleasures targeted by Pawlikowski emerge from a quasi-mechanic conjuring of pieces of cultural memory that contain meanings, without recreating these pieces as artistic organs that would infinitely produce meanings in the continuous interaction with the spectator. While draining the last bits of life from the images, it makes them speak the pure language of cinematic reason, which is one for everyone and, thus, belongs to no one. It is a language of no style. It reduces personal experience to an alphabet of ready-made clichés, cataloged in European culture and in the collective psychology of its consumption, in order to unleash cultural reflexes that allow the spectator to sympathize with what he watches without getting involved in the personal effort of seeing, or understanding. It is a kind of twisted democracy of art that says that every vote counts while there is nothing to choose. Although the film is partly inspired by the story of Pawlikowski’s parents, no one lives in Cold War, and no one moves but the debris of stories which have never found anyone courageous enough to tell them, stand cemented in monstrous postures, signs of aborted passion, almost shameful in their effort to last. Isn’t it a touching picture?

“If the utterly compelling brutality of the musicians’ faces recalls the genius of Pasolini, this moment, for all its comparative brevity, evokes Tarkovsky”1, comments one critic. And she is quite right: the film does “recall” and “evoke” not only Tarkovsky and Pasolini, but also jazzy Paris, chilly Poland, images of love, suffering and sacrifice. The obvious pleasure that the critic takes in this nonchalant name-dropping is reflective of things she is talking about. The brutal face as a sign of Pasolini, the abandoned church as a sign of Tarkovsky, Antonioni as the name of a bar, Paris as the city of love – this is exactly the disemboweled language of cinematic reason I was referring to earlier.

Leave a Comment