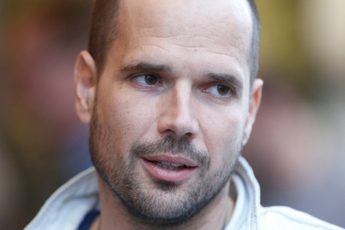

We met Slovenian filmmaker Damjan Kozole during the Trieste Film Festival, where he presented “Spare Parts” 15 years after its making. Kozole speaks about the idea behind “Spare Parts”, his career beginnings, and the future of cinema.

Made in 2003, Spare Parts was programmed again this year at Trieste as part of the ‘Wind of Change’ program. Do you feel a lot has changed in the meantime?

It is quite strange to return to the same festival with the same film after 15 years, but of course it is an honor. More or less all of my films are screened here so I do feel at home. I remember in January 2004, people didn’t believe the story of Spare Parts in Slovenia or Trieste. In 2016, I went back to the same location where I shot Spare Parts and shot a new film about immigration, a ten minute, one shot documentary called Borders which was still shocking 13 years later.

What inspired you to make Spare Parts?

On holiday in Croatia in the year 2000, I met the hero of my youth, a speedway champion from my hometown Krsko. We were in the same camp, we got to know each other and what he told me became my starting point for the film. He needed money and was smuggling refugees but thought of himself as a humanist, and I believed him. The Slovenian Film Fund did not believe that Slovenians were smuggling immigrants and they thought it was too dark and immoral to humanize two smugglers. But in 2003, there still wasn’t anybody talking about the refugee crisis so I made Spare Parts.

The film gives some insight on the many borders that make up the region around Trieste and Slovenia. How does this border situation affect your work?

Well my DOP is from Belgrade, I’ve edited films in Zagreb, we cooperate with Trieste a lot… There’s a good ambiance of unofficial collaboration.

What about Ljubljana, your own capital? What is your favorite thing about it?

Definitely the airport! You can escape whenever you want. Ljubljana is nice but a little bit claustrophobic sometimes, so it’s important to be able to escape. We can drive to get coffee in Trieste and it is one hour to Croatia and the coast in the car. It’s good to take a break.

All that traveling! Does that explain the new, four country co-production that you are currently making?

Yes, I finished shooting Half-Sister in December. It’s a Macedonian, Serbian, Croatian and Slovenian co-production. I’m in the process of editing.

How much time do you usually spend on that process?

It depends, this one was very well prepared so I expect to finish in a month and I’ve done a month’s work already. After that there’s the music to add and technical post-production. Sometimes you spend 6 months and sometimes everything works and it’s done in 3 weeks.

What’s the longest you’ve spent in post-production?

Probably more than half a year.

While we are on the topic of making films, your debut The Fatal Telephone Call, is a film on the same subject. When did you fall in love with cinema?

I started with photography in primary school and I planned to study architecture, so my first loves were really photography and architecture. I slowly matured into film. I started shooting super-8 films in the 5th or 6th grade and things like the French New Wave and Jean Vigo developed my passion for cinema.

I applied to the Ljubljana Film School but after 3 days of auditions I was refused. This led me to meet a guy who is still my producer after 30 years. He was working in a student association and they did a retrospective of Fassbinder. I managed to convince him to make a film with me and that is how The Fatal Telephone Call was made, to take revenge on the school. It must have been one of the first independent films made in Yugoslavia. In the 80s it was impossible to make a film without the permission and control of one of the republic’s 6 film centers.

How did you succeed then?

We were very young and probably the story of how we made the film is more interesting than the film itself. I remember we shot on 16 mm black and white film which we got cheap from the national TV station only to realize that it had expired 3 years before. Luckily it turned out okay. It was impossible to edit the film in Ljubljana and so I met with a Croatian filmmaker who helped me to edit the film in Zagreb.

So is it safe to say the film is influenced by the New Wave?

Well more like Wim Wenders and Jim Jarmusch in black and white, two guys who are madly passionate about cinema.

What’s your opinion on Stranger than Paradise?

Stranger than Paradise is definitely one of my favorite films, it’s a part of my youth. It really influenced me as filmmaker.

Your catalogue has gotten darker and darker with time however…

I remember when Spare Parts was screened at the Berlinale, there was a review that said my film was the darkest one in the program and I couldn’t figure out if it was a compliment or not.

In 2008 you made Forever, a film about domestic abuse. Why did you shoot it in your own apartment?

We shot that film in 2007/8 while there was a right-wing government in power. They claimed that all Slovenian filmmakers were communist and blockaded the film industry for over a year. During that time, I decided to film Forever in protest. We got two cameras for free for 7 nights. I wrote the script in 7 days, shot the film in 7 days, and the editing process was very short. It was premiered at Rotterdam where it opened up a serious discussion on modern culture and cinema in Slovenia.

Does friction and conflict help you create?

Society is what inspires me, I always try to catch the spirit of our times.

Do you find it easy to find inspiration for your films?

It depends, my films are always small stories. The starting point is usually some small detail, a feeling. Nightlife for example, which won at Karlovy Vary Film Festival, came from a scandal in Slovenia about 3 years ago. 3 bullmastiffs attacked their owner, a very famous Slovenian doctor. The doctor was found dead in a courtyard in February in the snow. The most bizarre thing is that he was completely naked and lying next to him was a huge wooden dildo. I read that the sister of this doctor arrived at the scene but had to wait for half an hour before she was allowed through and so my starting point for Nightlife was the idea of this woman’s fear of the unknown.

When you are not making fiction inspired by real life events, you are making documentaries. What is your relationship with the two mediums?

Slovenia is so small that you need to wait 4 or 5 years to make another film after a big success. In the meantime I come across so many interesting things and so I try to capture them in documentaries. Documentary is much more relaxed than fiction and I try to open up subjects which are very important to me, things that get swept under the carpet.

Do you feel that film has a strong future?

I mentioned Borders before. I knew this wave of refugees was coming and I knew I needed to do something as a filmmaker and as a human being. My moral dilemma was that I was reaping benefits from the tragedy of others so I reduced my idea of a feature documentary to a short. Then I reduced the screenplay, the music and the text. Finally, I made the film in one single shot. When I showed it to an audience, it got such a strong reaction. I thought in that moment that if one shot still has such power, then cinema definitely has a future.

Thank you for the interview.

Leave a Comment