On the Uselessness of Memory

Archival Film, the Jugoplastika Factory, and the Imaginary of the Yugoslav Socialist City

Vol. 137 (September 2023) by Ana Grgić

In memory of Dubravka Ugrešić.

We might be more likely to say “what’s the use?” when the uselessness of something had not been apparent right from the beginning, when we have given up on something that we had expected to be useful such that to become exasperated can point not only to what, that which is now deemed pointless, but also to who, those who had assumed something had a point.

– Sara Ahmed, What’s the Use? On the Uses of Use.

What kind of culture comes into being on the ruins of a system – and in an age which likes cultural labels, will it be called ‘post-communist’ or ‘post-totalitarian’?

– Dubravka Ugrešić, The Culture of Lies.

The “last Yugoslav writer”, Danilo Kiš, described the banality of kitsch in art and culture as “indestructible as a plastic bottle” (Homo Poeticus).1 If a plastic object is undesirable because of its synthetic ideology and perennial nature, our resistance to the ravages of time and the atmospheric conditions threatening our planet’s ecosystem, conversely, celluloid film is quite prone to moisture, heat and a slow yet inevitable decay. Moreover, the easily manipulated synthetic material, plastic, has become synonymous with 20th century postwar consumerist society and the Western capitalist lifestyle, and is ubiquitous in almost all areas of human production and everyday life. We could say that its “utilitarian” and “use” value has shaped the way we work, live, and socialize. In a similar way, “useful” film has been used “to do something in particular”, as an integral part of broader “useful culture”, which “shapes debates, moves populations, directs capital, furthers authority, and ordains the self”.2 Though “industrial and commissioned films are definitely among the most prolific formats or genres in film history”, little scholarship has been dedicated to their study as objects of knowledge,3 a fact that leaves a large gap in our understanding of this particular type of film – useful film’s aesthetics, narrative, practices, and trends. Since “industrial films transcend the boundaries of the material object of film found in the archive and refer to a dispositif, a complex constellation of media, technology, forms of knowledge, discourse, and social organization”,4 their study and analysis transcends the boundaries of the film-text itself, reflecting a broader interconnected network of meanings and discourses responsible for its creation. Moreover, addressing archival non-fiction films, which constituted the majority of film production during Socialist Yugoslavia, is also a way to challenge and decenter the Cold War optics of dissident versus state propaganda in the fiction filmmaking canon, which has informed much knowledge on cinemas from Socialist-bloc countries, dictating the value regime that decides which films, filmmakers and styles are worthy of study and viewing, and which are not. Mignolo and Vazquez have argued how the “modern aestheTics have played a key role in configuring a canon, a normativity that enabled the disdain and rejection of other forms of aesthetic practices”, or “other forms of aestheSis, of sensing and perceiving”.5 Thus, they argue, a “decolonial aesthesis” can engage in “a radical critique to modern, postmodern and alterrmodern aestheTics” and as such it figures as a site of enunciation from which we can recognize and make visible those aesthetic practices that were excluded from the canon of modern aestheTics.6

This paper deals with both the destruction of a successful Yugoslav-era factory that manufactured plastic products, and the suppression of the collective memory of Yugoslav Socialist production, industry, and modernity. The paper will base its observations on a surviving archival work copy of a promotional (and “useful”) film titled 25th Anniversary of Jugoplastika (25 Godina. Jugoplastika, 1977), conserved at the state archive in Split, Croatia (Title Image). This promotional film was commissioned by the Jugoplastika factory in the 1970s to mark the anniversary of its creation, and was made by the local film production company Marjan Film, the most important producer of utility films for the city and its surroundings.7 The Jugoplastika kombinat, a multi-plant complex organization of associated labor, employed some 13,000 workers at the height of its production in the 1980s, and sold its assortment of around 3000 products in over 200 stores across the territory of former Yugoslavia. More importantly, this factory occupied a prominent place in the economic and social development of the city of Split and its surroundings, accounting for 25% of the local workforce, with 80% women employees. Today, visible traces of the former factory have been erased from the urban fabric of the city. When I started researching useful film in former Yugoslavia,8 I decided to focus on non-fiction films made about the Jugoplastika kombinat, not only to circumscribe my investigation to a precise object of inquiry, but also to get a better understanding of the social, industrial and economic heritage of the city and its society during Socialism from the vantage point of an era of neoliberal values, political uncertainty, a collapse of industry, unemployment, and mass development of tourism. The demolition of the Jugoplastika factory, once a symbol of the “socialist city”, and the erection of a shopping mall in its place, represents a shift in the regime of values, from a self-sustainable production society to a debt-ridden consumer society.9

The Socialist city shared similar characteristics with the modern, industry-led urbanity of the 20th century, but was also defined by a classless logic in its design of urban and industrial spaces, as well as Socialist mass-housing projects. In other post-Socialist countries, former industrial sites and factories either lay derelict, leaving behind a serious problem of brownfields in the region, or alternatively were repurposed or refurbished to high-tech or mixed space use.10 According to Blagaić and Kirin, due to women comprising a large majority of Jugoplastika’s workforce, “the story of one multi-plant factory is a story of the greatest losses of the transition economy”,11 as women workers, with the closure of the factory, have become invisible from the public and media sphere of the city. Today, the surviving fragments attesting to the factory’s heyday are relegated to a few non-fiction films and the dusty paper archives of the firm’s financial and operational records conserved at the state archive in Split. Starting from the premise that “archives only become useful when they are being used”12 – after all, the archive “just sits there until it is read, and used and narrativized”13 –, I engage with the surviving archival work copy of 25th Anniversary of Jugoplastika in an attempt to conjure its “use” value, despite the perceived contemporary “uselessness” of its discourse in post-Yugoslav times. It is also an act against oblivion, so powerfully described by Boris Buden, Croatian philosopher and cultural critic, who draws attention to continuities, opposing them to still images of the past existing only as a form of representation and not as a form of historical experience.14 Perhaps, this approach can also constitute a modest way of engaging in decolonial thought, to challenge Cold War dialectics and their effects on theory and politics, a strategy recently proposed by the editors of Decolonial Theory & Practice in Southeast Europe (Katarina Kušić, Philipp Lottholz and Polina Manolova), which can point towards “new entry points for societal activism and struggle against neoliberal restructuring and the internalization of essentialist and hierarchizing ways of thinking, acting and knowing”15. My contention is that we must return to the archive, in order to decolonize the contemporary regime of knowledge and power structures, not because the archive has a claim to an objective truth or because it constitutes an unmediated source of the past, but rather because it opens up to the potential of an affective and political realm. Perhaps, the work copy of this archival film can allow us to remember the positive potential of Yugoslav Socialist heritage, such as the principles and ideas behind social justice, public welfare, and worker’s rights.

The Discourse of Use

The disintegration of former Yugoslavia also entailed the disappearance, suppression and forgetting of a whole set of values associated with a particular style of “Yugoslav socialism” that encompassed anti-fascism, worker’s self-management, multiculturalism, and multinationalism. In the post-Yugoslav context, such values were rendered use-less, in particular as the new republics were busy creating new exclusively ethno-national histories, identities and memories. Along with the now “useless” values, in the post-Socialist era other items of Yugoslav everyday life were also deemed useless or, alternatively, they became museum objects of “subversive” and “politically and morally disqualifying” Yugo-nostalgia. Writing in the aftermath of the Yugoslav wars, Dubravka Ugrešić, a writer and intellectual persecuted alongside other feminists for her anti-war views, argued: “It is perfectly possible that the war has put an end to collective Yugo-memory, leaving behind only the desire for as speedy as possible oblivion”.16 This post-Yugoslav oblivion extends to all areas of cultural, social, political, and economic aspects of former Yugoslav everydayness. Within a climate of historical repression and distortion, acts of nostalgia (even in the form of collecting everyday objects manufactured in former Yugoslavia by companies which no longer exist) can sometimes constitute veritable acts of individual or collective rebellion and forms of resistance today. Linda Hutcheon notes how one “should never underestimate the power of nostalgia, especially its visceral physicality and emotional impact”, whose power lies in double articulation between “an inadequate present and an idealized past”.17 According to Boris Buden, the struggle against Communism in Croatia is even more active nowadays, three decades after the end of the regime, and this anti-Communism is connected to right-wing nationalist mobilization (as witnessed in Poland, Croatia and Hungary), a symptom of the crisis of the post-Communist narrative and its logic.18 Similarly, the Romanian philosopher Ovidiu Țichindeleanu argues that “anti-communism was instrumentalized as the regional articulation of the coloniality of power in the former socialist bloc”, while the contemporary regimes of truth instituted “a normative history that asks people to take an absolute distance from their own past”.19

A researcher delving into the remnants and fragments of the common Yugoslav past is soon confronted with an abundance of suppressed, neglected and “useless” archival artifacts, in particular, films and documents produced during the time of SFR Yugoslavia, often with the aim to promote a particular type of Yugoslav Socialism and its associated values. In the aftermath of Yugoslavia, not only did these values lose their “use”, but so many physical sites where one could say the concept of Yugoslavism had once lived have been erased (such as names of streets and even towns), destroyed (such as monuments, buildings, factories, memorabilia, books) or transformed (institutions, buildings, museums). If such artefacts have fallen into disuse and been rendered useless by virtue of the collapse of a system, we can consider them “lost” in Sara Ahmed’s terms (“use becomes an obligation to keep something alive […], use becomes necessary in order to avoid something being lost”). Further, as Ahmed argues, the word “use” evokes everyday life,20 and for this reason I will relate and apply the notions of “usefulness” and “uselessness” to my analysis. In particular, the notion of “use” relevant to Yugoslavian-era values and ideology will be examined in relation to the post-Yugoslav and post-Socialist context and its everyday experience of urban space.

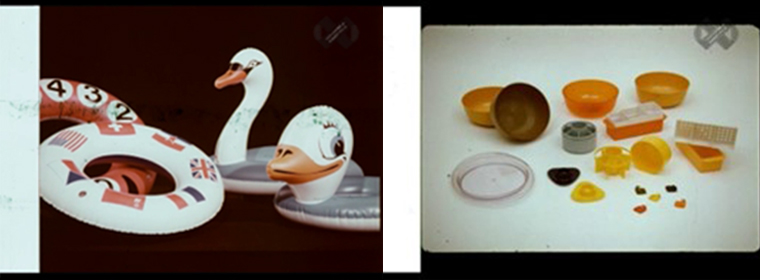

The work copy of 25th Anniversary of Jugoplastika lasts approximately 14 minutes and is composed of nearly 300 shots, each promoting the various sections of the Jugoplastika factory, which manufactured a wide range of plastic-derived products. Following each section of the Jugoplastika factory, the so-called “pack shot” (the still or moving image of a featured product, usually including its packaging and labeling, used in an advertisement to portray the product’s reputation and brand) highlights their most representative commodities, such as the production of bags and shoes for the German sports giant Adidas. The multi-colored and vibrant array of consumer products featured throughout the promotional film, in addition to a fast alternation of views, aim to build up the viewers’ desire for consumption. A comparison between this promotional film and any promotional film from “Western” consumer societies would reveal more similarities than differences. In particular, a common emphasis on the creation of desire, in particular among women, for clothing, accessories or household items, is conveyed through the inclusion of shots inside the Jugoplastika department stores showing women shopping or shots of fashion shows featuring the latest trends. However, while a sort of Socialist (or rational) consumerism seems to be encouraged, there are important differences, such as views of the workers’ resort built on the nearby island of Šolta, the health clinic, or the women’s football club, Socialist-era collective activities organized by the Jugoplastika factory for its employees.

The post-Socialist lieu de mémoire

With its headquarters located in the second largest Croatian city, Split, the Jugoplastika factory was founded in 1952 to produce an ever-expanding assortment of everyday products ranging from clothing, footwear, accessories, and homeware to car parts fabricated from PVC (polyvinyl chloride) and new synthetic materials (Figures 1 and 2). This type of industry marked post-war Socialist modernization and the industrial production shift from the “machine-age” to the “plastics age”21 The Jugoplastika kombinat, “one of the strongest symbols of the country’s modernization, technological innovation and novelty of goods and brands connected with accessibility, practicality, happy childhood, leisure, and free time”,22 was demolished in 2003-2004 and replaced by apartment blocks, a shopping mall, and a hotel, thereby helping visually erase the city’s Socialist industrial past. This symbolic event can be seen in an amateur video that captured the demolition of the factory’s central building, which used to be the symbol of Split. This video figures as a traumatic audiovisual reminder and document of post-Yugoslav historical revisionism and its acts of erasure of collective “Yugo-memory” (Figure 4). Watching the video, it is difficult not to compare the explosive noise of the detonation with similar sounds of bombs and machine-gun fire during the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s. The violent break-up of former Yugoslavia, mediated ad-nauseam in the countries of former Yugoslavia and around the globe, seems to find its violent echoes in the systematic destruction of Yugoslav-era factories, industry, and collective work, so forcibly and symbolically captured by this amateur video. Moreover, in post-Socialist times, once thriving Socialist urban spaces have been rendered useless, by virtue of the fact that Yugoslav Socialist values of collectivism, worker’s self-management and forms of social ownership should be replaced by individualism, market competition, and private ownership.

Therefore, whereas the physical space of Yugoslavism and Yugoslav Socialism has disappeared, giving way to a shopping mall (named “Joker” in what is most likely an ironic coincidence), the ubiquitous symbol of Western-style capitalism and contemporary consumerist society, the archival film conserves the traces of this particular instance of “immaterial subjective-social worlds and their meanings” through “the representation of a momentary human experience”.23 In a way, the disappearance of the physical site within the urban space, with the demolition of the factory and all its traces, invests the surviving non-fiction films about the factory with what Pierre Nora called “lieu de mémoire” (site of memory). According to Nora, in modern societies, the “milieux de mémoire”, real environments of memory, are gone. Contrary to that, certain sites, where a sense of historical continuity persists, embody memory, and Nora terms these as lieux de memoire.24 Memory sites can encompass a wide variety of objects, from the most material and concrete object, geographically located at a specific place, to the most abstract and intellectually constructed object. Her views about the function of memory – that “[memory] takes root in the concrete, in spaces, gestures, images and objects” – can be linked to the Jugoplastika factory.25 Its demolition erased from the fabric of the city its material, visible and ideological function as a real environment in which memories can be continuously generated (by its workers or its operations, for instance), and alongside this disappearance, an integral part of the city’s Socialist-era heritage was gone as well. In its place, the new shopping mall represents the new regime of values that are linked to a post-Socialist, neoliberal capitalist society, which has largely turned from producing, to the consumption of goods. Given that the erasure of the factory simultaneously constitutes the erasure and suppression of the city’s Socialist past, and that no commemoration plaque nor monument stand today to attest to its existence, the only affective remainder and reminder of the factory resides in mediated representations, in other words in surviving archival materials that are articulated in the form of still and moving images.

Consequently, these non-fiction archival films about the Jugoplastika factory can also be considered sites, in as much as they are material, symbolic, and functional.26 Given the erasure of actual physical sites and the reliance of post-Socialist memory on filmic archives, we can infer – with Nora – that “modern memory is, above all, archival. It relies entirely on the materiality of the trace, the immediacy of the recording, the visibility of the image”.27 Certainly, the promotional film in question, made for the 25th anniversary of the factory’s existence, is far from being an objective recording and yet it constitutes a document of Yugoslav society culture at that particular moment in time. The archival fund of the Jugoplastika kombinat conserved at the state archives in Split does not hold any specific documentation about this film, however, considering that the factory regularly participated in international fairs, this film likely had a dual promotional function: a) an external and economic function, that is the promotion of the products of the Jugoplastika kombinat to the international market and stakeholders, and b) an internal and ideological function, that is the celebration of 25 years of existence and successful work within the context of Yugoslav state socialism and its associated values. A closer look at the content and representational strategies of this promotional film allows us to understand how discourses on modernization and technological innovation were put at the service of a new culture of “socialist consumerism”, and the shaping of the imaginary of an ideal “socialist” city.

The Yugoslav Socialist city imaginary

The promotional film 25th Anniversary of Jugoplastika contributes to the construction of the imaginary of the Yugoslav Socialist city, inasmuch as it visually combines urban spaces of living, work, and leisure that are characteristic for the Yugoslav “third way” of Socialism. In this manner, the film participates in the promotion of the Yugoslav “market socialism” and its unique (and perhaps utopian) political ideology, which combined capitalism and Socialism, underpinned by the philosophy of the worker’s self-management system. This archival film becomes a visual remainder and reminder of possible Socialist sites “of emancipatory and inclusive action” that “include autonomy, economic democracy in the form of self-management” such as workers’ councils and collectives “and solidarity across social groups, categories and international borders”28.

According to urban geographers, both the capitalist and the “socialist” city constituted models of the 20th century modern, industry-led urbanity. There were however key differences, products of the more Socialist drives of the spatial production process, namely, the state’s monopoly on urban development and the “classless city” structure that were pursued by Socialist authorities.29 Furthermore, Ivan Szelenyi30 notes several distinguishing features that marked the urban logic in Socialist nations: less urbanization (less of the population living in urban spaces), less urbanism (less diversity and marginality), and distinctive spatial structures shaped after the goals of the “socialist city”.31 Perhaps the two most distinguishing features of the “socialist city” and its urban aesthetics are Socialist mass-housing estates and industrial giants. While commercial spaces were under-allocated, “industrial land occupied a much higher proportion of the total land area in socialist cities than in cities farther west”.32

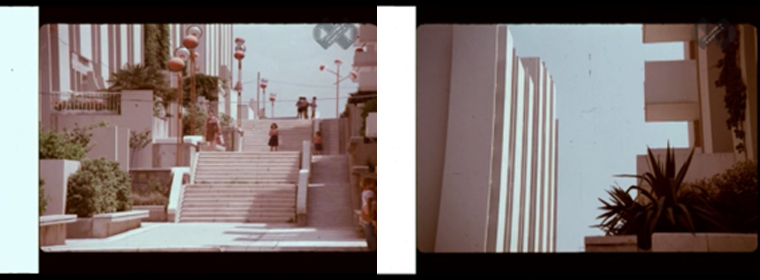

In Yugoslavia, the “third way” Socialism meant that workers had a certain amount of power, not only in factories and enterprises, but also in shaping local architecture. After the split with the Soviet Union in 1948, this became a distinctive feature of the Yugoslav political and economic system (known as workers’ self-management), which allowed individual workers to participate in Yugoslav enterprise management through their respective work organization. Each work organization was governed by a worker’s council, which was responsible for electing the management board that ran the enterprise. In addition, the right to housing in Yugoslavia was protected by law, which meant that many institutions and enterprises provided homes for their employees. For instance, the Jugoplastika kombinat allocated flats to around 1400 of its employees until 1982 (which translates to roughly 12% of their workforce). In 1960, a new legislation enabled competitive self-managed construction enterprises to undertake Socialist mass-housing development projects, a right previously reserved for the Socialist state construction services. For this reason, most of the building designs in Yugoslavia were the result of competitions, which resulted in individualism rather than uniformity, as well as a characteristic modernist architecture (Figure 6). Modernism in Yugoslavia was influenced by diverse architectural styles, from Le Corbusier and Brutalism to the International Style, resulting in different approaches, which at times drew on and combined local and regional elements from the city’s historical architecture. This is visible in the construction of Split 3, the modern part of the city built in the 1970s to house 50,000 people, where different architects contributed to one of the largest urban planning schemes33 composed of striking housing blocks interconnected with stylish pedestrian streets lined with gardens and local Dalmatian stone (Figure 5). Moreover, this approach exemplifies the idea of “small socialism”, where “small urbanism” (theorized by the Serbian architectural theorist Bogdan Bogdanović in 1958) should be conceived alongside a more “human scale” and help emphasize the “local characteristics and regional diversity of spaces across Yugoslavia”.34

Split was partially demolished in the Second World in the Allied air strikes in 1943 and 1944, and, in the immediate postwar period, ruins were cleared as damaged infrastructure and buildings were rebuilt. The city soon grew into a regional administrative, economic and transport center of Dalmatia, also affected by a housing shortage.35 Constructions of new apartments along the perimeter of the historic center were gradually undertaken (in Diocletian’s palace and its immediate surroundings), what came to be known as “Split 2”, an urban area with standardized buildings and residential high-rises that still remained disproportionate to the population growth.36 With the city of Split witnessing an ever-growing demand for apartments in the 1960s due to the influx of newcomers (of around 3% annually), the local work organization (“Poduzeće za izgradnju Splita”, PIS) thought that a new urban planning project comprising several different facilities (residential apartments, commercial spaces, schools, and recreational spaces) would provide a solution. In November 1968, the PIS and the Association of Architects held a general Yugoslav urban design competition for Split 3 and received 18 proposals.37 The winning team were a Ljubljana-based team of architects, Vladimir Music, Marjan Bezan and Nives Starc, who conceived the design as a forum of urban life in Socialist Yugoslavia, under “the belief that functions in the city should not be separated”. Their proposal included characteristic spaces for living, work and leisure that respected “the human – inhabitant and walker – allowing her/him to have a view of the sea and the sun from the apartment”.38

The interplay of individualism and collectivism, and the specific political ideology of “market socialism”, developed and championed in Yugoslavia following Tito’s break with Stalin, would also be reflected in the urban design of the cities. Analyzing the opening images of the promo film 25th Anniversary of Jugoplastika, the factory is situated as emblematic of the city of Split itself, its potent symbol. The first views classify Split as a “typical Mediterranean city”, an idyll on the Adriatic Sea, by showing its oldest recognizable architectural feature (the view of Diocletian’s palace from the sea) in the soft light of the dusk, thus creating a romanticized postcard-like image (Figure 7). This is significant because the development of competitive tourism was an important part of Yugoslav Socialism. Already in the 1960s, new hotels and resorts on its coastline had become an expression of its political philosophy and social approach, designed as open and free flowing in order to encourage inclusivity and participation (see for example, the Medena hotel complex built near the town of Trogir in 1971). The film slowly introduces us to the new part of the city in the vicinity of the factory, lined with Socialist blocks and wide streets (Figure 8), before cutting to the entrance gates of the Jugoplastika factory to record a truck that crosses them. On its side, a huge stencil reading “Kombinat Jugoplastika. Split – Jugoslavija” visually establishes the spatial coordinates for the viewers. Successive views show employees going to work in the factory, followed by an aerial view zooming out from the factory gates to reveal its central location and situate it within the urban space. The film then cuts to a graphic insert marking the Jugoplastika kombinat’s various factories and manufacturing plants scattered across Dalmatia (Figure 9). The next images present the most representative features of the city of Split, such as the shipyard and its transportation (the train station and the airport), symbolically highlighting how the city is connected to other places and can be reached by land, sea, or air (Figure 10).

The film exhibits a significant departure from the necessity and frugality-like lifestyle of post-World War II Yugoslavia, which was focused on re-building the country, and marks a shift to a more “Western”, consumer-like lifestyle, where the emphasis lies on enjoyment and leisure instead of work. Analyzing the surviving work copy celebrating the anniversary of the Jugoplastika kombinat’s activities, we can infer that the factory participated in the construction of a country that had access to quality products and maintained a consumer-oriented lifestyle, thus blending Socialist and Western values. The durability, flexibility, and malleability of plastic, symbolic of post-war capitalist consumer societies, is foregrounded and exemplified in the film, confirming Yugoslavia’s competitive place in the global technological, scientific, and economic sphere. Indeed, Yugoslavia was very much integrated into the world capitalist order, a fact the film confirms by showing the goods the factory manufactured for Western brands such as Adidas, its participation in international fairs and its business dealings with both Western and Eastern countries, as its still images of London, Paris, and Moscow attest.

Fragments, Traces, Hauntings, and the Yugoslav Socialist Utopia

De Certeau writes:39

whatever this new understanding of the past holds to be irrelevant – shards created by the selection of materials, remainders left aside by an explication – comes back despite everything, on the edges of the discourse or in its rifts and crannies: “resistances”, “survivals”, or delays discreetly perturb the pretty order of a line of “progress” or a system of interpretation.

Unlike memory, “plastic is forever”, say the ecologists. It takes anywhere from 20 to 500 years to decompose, and even then, it never fully disappears but gets smaller and smaller, perennially haunting our environment and microcosmos. Plastic therefore represents both the peak of human and technological progress, and ecological planetary destruction. According to all logic, plastic will survive the fallibility of human memory. For a factory that once participated in the creation of what could be seen as a “plastics utopia” of Yugoslav Socialist everydayness, both its material and metaphysical disappearance from the city’s urban landscape does not come without irony. The plastic toys manufactured by Jugoplastika are avidly collected and conserved in private collections in territories across former Yugoslavia and beyond, surviving the collapse and disappearance of the Yugoslav Socialist utopia and its associated values of an alternative political and social system based on collectivism, anti-fascism, anti-colonialism, workers’ rights, social justice and welfare, multiculturalism and multinationalism. What can Vučko, the plastic mascot of the 1984 Sarajevo Winter Olympic Games, (now sold online on second-hand websites such as the one pictured in Figure 11), manufactured and painted by the women laboring at the Jugoplastika factory, still tell us? According to Linda Hutcheon, nostalgia and irony share a secret affinity, a double structure and “an unexpected twin evocation of affect and agency, – or emotion and politics.”40 In 2022, the sociologist Petra Sinovčić, together with other colleagues from the local association Domina, produced a short documentary film, combining archival footage and testimonies of former women employees from the Jugoplastika factory in an effort to document women’s histories, noting how the factory enabled a great number of women to enter the workforce for the first time and consequently contributed to their emancipation.41 The screening of the documentary was attended by former Jugoplastika workers who expressed both nostalgia for the past, but also provided useful insights on the organization of work, labor conditions, and family life during the Jugoplastika years. They highlighted the solidarity existing among workers, their creativity and the dynamics of working tasks, housing fund contributions and opportunities for further education, but also negative aspects, such as being exhausted depending on the work shift, and nepotism.42 Such local commemorations provide spaces for sharing personal and collective memories, whereas the re-use of archival materials in newly produced documentaries and works constitute opportunities for delving into experiences of everyday culture inasmuch as they open up to the regime of affect and politics through the very act of viewing. They constitute acts of remembering.

What’s the use of remembering? According to Svetlana Boym, “fundamentally, both nostalgia and technology are about mediation”.43 It is the cinematic apparatus and technology that allows the preservation of the traces of the Jugoplastika factory, its employees, and its collective memory, all physically vanished from the urban fabric of the post-Socialist city. It is nostalgia that can be a “freedom to remember, to choose the narratives of the past and to remake them”.44 Today, at a time of increased political polarization across Europe and at a time when the shortcomings of the capitalist world system and global inequalities and disparities become more palpable by the day, announcing the looming threat of ecological emergencies to our planet’s ecosystem, we need to engage in decolonial endeavors of our own past narratives more than ever. The Yugoslav Socialist dream, which sought to build and occupy a third space, an in-betweenness of Socialist and capitalist ideologies, came crumbling down along with the disintegration of former Yugoslavia and its whole set of associated values. To remember this alternative political philosophy is to see and critically analyze the surviving work copy of this archival film. To see again how, through the manufacturing of plastic-derived goods that would enhance all aspects of life for Yugoslav citizens, the Jugoplastika kombinat participated in the shaping of everyday life in former Yugoslavia. How this everydayness encompassed life, work and leisure, and notions of both individualism and collectivism that here do not constitute mutually exclusive concepts, but rather, projected desires of a Yugoslav Socialist utopia, something to tend to, to strive to; something to be conceived as a possible future.

References

- 1.“The common cultural heritage […] is now dead, just as its authors are. […] The former Yugoslav cultural centres have sunk into a torpor of cultural autism, the air there is heavy not only with aggressive misery but with stupidity and banality `indestructible as a plastic bottle’ (Kiš)’’ (Ugrešić, Dubravka. 1995. The Culture of Lies. State College: Penn State University Press, 161-162).

- 2.Acland, Charles R. and Wasson, Haidee (eds.). 2011. Useful Cinema. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press.

- 3.Hediger, Vinzenz and Vonderau, Patrick (eds.). 2009. Films that Work: Industrial Film and the Productivity of Media. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 10.

- 4.Hediger, Vonderau 2009, 11.

- 5.Mignolo, Walter, and Vazquez, Rolando. 2013. “Decolonial AestheSis: Colonial Wounds/Decolonial Healings’’. Social Text, 4. Source: https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonial-aesthesis-colonial-woundsdecolonial-healings [accessed on 29 June 2023].

- 6.Mignolo, Vazquez 2013, 4-15.

- 7.The copy of the film conserved at the state archive in Split is a 35 mm positive work print in color with no sound. The film was made by a collective, composed of a university professor and other film professionals, and no one is credited as director, cinematographer, editor, etc. The Marjan film collection conserved at the state film archive in Split has around 500-600 titles, composed of documentary, experimental and promotional experimental films, including 10 feature fiction films.

- 8.I would like to thank the archivists at the State Archives in Split and the Croatian Film Archive in Zagreb, and in particular, my colleagues Vendi Ganza Marušić and Lucija Zore for helping with my requests and for providing access to the collections and films. This research was financially supported by the Faculty of Theatre and Film at Babeș-Bolyai University. I am also grateful for the advice and help provided by colleagues Boris Poljak and Sunčica Fradelić at Cine Club Split.

- 9.Blagaić, Marina and Kirin, Renata Jambrešić. 2013. “Ambivalentno nasljee socijalističkih radnica: slučaj tvornice Jugoplastika’’. Narodna umjetnost – Hrvatski časopis za etnologiju I folkloristiku 1:40-72; Sapunar, Dora. 2013. “Kako se odnositi prema simbolima vremena ili što veže Pruitt-Igoe s Jugoplastikom?’’: http://www.kustoskaplatforma.com/prosla-izdanja-kp/kp-2011-2012/teren/dora-sapunar [accessed on 2 April 2013].

- 10.Hirt, Sonia. 2013. “Whatever Happened to the (post)socialist City?’’ Cities 32, no. S1, S33.

- 11.Hirt 2013, S47.

- 12.Ahmed, Sara. 2019. Whats the Use? On the Uses of Use. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press.

- 13.Steedman, Carolyn. 2001. Dust: The Archive and Cultural History. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 68.

- 14.Genova, Neda. 2018. “A Better Past is Still Possible. Interview with Boris Buden’’. LeftEast, https://lefteast.org/a-better-past-is-still-possible-interview-with-boris-buden/ [accessed on 29 June 2023].

- 15.Kušić Katarina, Lottholz, Philipp, and Manolova, Polina (eds.). 2019. Decolonial Theory and Practice in Southeast Europe. Sofia: dVERSIA, 12.

- 16.Ugrešić 1995, 231.

- 17.Hutcheon, Linda, & Valdés, Mario J. 2012. “Irony, Nostalgia, and the Postmodern: A Dialogue’’. Poligrafías. Revista De Teoría Literaria Y Literatura Comparada, (3). https://www.journals.unam.mx/index.php/poligrafias/article/view/31312 [accessed on 29 June 2023].

- 18.Genova 2018.

- 19.Țichindeleanu, Ovidiu. 2013. “Decolonial AestheSis in Eastern Europe: Potential Paths of Liberation’’. Social Text Online, Retrieved from https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonial-aesthesis-in-easterneurope-potential-paths-of-liberation/ [accessed on 29 June 2023].

- 20.“Use brings things to mind. Perhaps the word use is workmanlike, with its “monosyllabic bluntness,’’ because of how it evokes everyday life.’’ Ahmed 2019, 6.

- 21.Spake, Penny (ed.). 1990. The Plastics Age: From Modernity to Post-Modernity. London: Victoria and Albert Museum.

- 22.Blagaić, Marina and Kirin, Renata Jambrešić. 2013. “Ambivalentno nasljee socijalističkih radnica: slučaj tvornice Jugoplastika’’. Narodna umjetnost – Hrvatski časopis za etnologiju I folkloristiku 1:40-72, 41.

- 23.Penz, François and Koeck, Richard (eds.). 2017. Cinematic Urban Geographies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- 24.Nora, Pierre. 1989. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de mémoire’’. Representations 26, Spring, 7-24.

- 25.Nora 1989, 9.

- 26.Nora 1989, 19.

- 27.Ibid.

- 28.Kušić Katarina, Lottholz, Philipp, and Manolova, Polina (eds.). 2019. Decolonial Theory and Practice in Southeast Europe. Sofia: dVERSIA, 21.

- 29.Hirt, Sonia. 2013. “Whatever Happened to the (post)socialist City?’’ Cities 32, no. S1, S29.

- 30.Szelenyi, Ivan. 1996. “Cities under socialism—and after’’. In Gregory Andrusz, Michael Harloe, and Ivan Szelenyi. Eds. Cities after socialism: Urban and regional change and conflict in post-socialist societies. 286–317. Malden: Blackwell.

- 31.Szelenyi 1996.

- 32.Hirt 2013, S33.

- 33.Kukoč, Višnja. 2010. “Razvoj Splita III od 1968. do 2009. Godine/ Development of Split II from 1968 to 2009’’. Prostor, 18, 166-177.

- 34.Robertson, James. 2021. “Small Socialism: The Scales of Self-Management Culture in Postwar Yugoslavia.’’ Slavic Review 80.3, 563-584.

- 35.Marinović, Hrvoje, Mlinar, Ivan and Tomšić, Ana. 2021. “Split 2 Housing Developments planned from 1957 to 1968’’. Prostor, 29, 75.

- 36.Marinović, Mlinar, Tomšić, 75.

- 37.Kukoč 2010.

- 38.Translated by the author from on the commission’s decision that was quoted. In: Kukoč, Višnja. 2010. “Razvoj Splita III od 1968. do 2009. Godine/ Development of Split II from 1968 to 2009’’. Prostor, 18, 166-177.

- 39.De Certeau, Michel. [1975] 1988. The Writing of History. Translated by Conley Tom. New York: Columbia University Press, 4.

- 40.Hutcheon, Linda, & Valdés, Mario J. 2012. “Irony, Nostalgia, and the Postmodern: A Dialogue’’. Poligrafías. Revista De Teoría Literaria Y Literatura Comparada, 22. https://www.journals.unam.mx/index.php/poligrafias/article/view/31312 [accessed on 29 June 2023].

- 41.Zarko, Jakov. 2022. “Bile smo obične radnice, ali smo se osjećale ka carice! S pismom smoišle na posal. Svi znaju za Escadu, Boss i Adidas, ali malo ko zna da su senjihovi proizvodi stvarali i kod nas, u Jugoplastici’’. Slobodna Dalmacija.

- 42.Zarko 2022.

- 43.Boym, Svetlana. 2001. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books.

- 44.Boym 2001.

Leave a Comment