Confronting Avant-Garde Utopia With Death

Igor and Gleb Aleynikov’s The Cruel Illness of Men (Zhestokaia bolezn’ muzhchin, 1987)

Vol. 109 (November 2020) by Emily Nill

In its extreme depictions of emptiness, alienation and brutal sexual violence, the Aleynikov brothers’ short film The Cruel Illness of Men (1987) can be characterized as an epitome of the Parallel Cinema movement in the late Soviet Union. What I want to discuss here is what lies under the film’s grim surface. The majority of research on Parallel Cinema and the Aleynikovs1 concentrates on their artistic reflection of late Soviet society as “an utter existential senselessness”,2 which is believed to be expressed through their use of explicit, horrifying images of inhumanity. In contrast to this interpretation, I will argue that in The Cruel Illness of Men a subversion of senselessness takes place through its specific combination of form and subject matter. By reflecting on the directors’ use of decidedly Soviet avant-garde aesthetics, methods and philosophy, I open up a new, utopian perspective on the Aleynikovs’ film. Where a lot of previous research sees its potential of subversion in the presentation of “a sick joke”,3 a “juvenile provocation”4 contradicting official media, I want to emphasize the critical potential of the directors’ engagement with the avant-garde.

When referring to the avant-garde in Russia and the early Soviet Union, a broad range of cultural activities striving to be at the forefront of modernity come to mind. Producing films, paintings, magazines, and architectural artifacts, artists were occupied with designing socialist visions which they were eager to put into practice. This art-becoming-life ideology, the utopian dream of changing society via art, and the idea of construction as its principle, links practices as diverse as Kazimir Malevich’s suprematism and Dziga Vertov’s documentarism. In the case of the cinematic avant-garde of the 1920s, this politicized perspective of revolutionary – or at least socially useful – art is characterized by a changing relationship of medium and audience. Filmmakers like Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov or Oleksandr Dovzhenko, however varying their works may be, each “didn’t want to create a distance between the film and the audience but to eliminate it.”5

In works such as Eisenstein’s Strike (1925), Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) or Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930), this idea of the artist as a constructor comes into play through the use of montage – not in the sense of establishing a continuity throughout the film, but by disrupting the viewers’ expectations and urging them to reflect on what they see. In other words, filmmaking here needs to be understood as a dialectical hypothesis in the viewers’ mind; the viewers transform what they see into a synthesis which can be converted into action. An example for this technique is the “collision”6 of seemingly unrelated shots in the final scene of Strike, where the dead bodies of the strikers are intertwined with the butchering of cows. The montage both implicates a visually compelling critique of social conditions as well as a potential trigger to unleash the viewers’ anger and their political will to exact social change. To sum it up in Eisenstein’s words: “We need not contemplation but action.”7 Furthermore, in 1920s avant-garde cinema, classical dramatical structures were suspended. Instead of following the classical curve from exposition over climax to catastrophe, avant-garde cinema is characterized by its affinity to the essay, recognizing the fragmented nature of both social reality and our perception of it.

Combining socialist themes of proletarian uprising, the celebration of progress, scenes of modern urban life as well as agriculture, these films, as Mikhail Epstein puts it, “tried to invent patterns for the future”8 for a conscious audience. According to Epstein, the main difference between Soviet avant-garde cinema with its utopian qualities and Parallel Cinema or Necrorealism is their diverging self-conceptions. Epstein diagnoses a “superiority complex” which fueled avant-garde art practice towards creating a different reality. In contrast, Soviet Parallel Cinema, which Epstein coins “rear-garde art”, had already accepted its own inferiority. This “post-utopian or anti-utopian” art of the 1980s “falls behind deliberately, inventing aesthetic forms of backwardness”.9 This new generation of filmmakers in the late Soviet era, including the Aleynikov brothers, embraced the aesthetics of dark, desolate environments, the hopelessness of social reality and acts of senseless violence instead of proclaiming a bright and utopian future. In The Cruel Illness of Men, this approach can be detected in its dark spin on the proletarian utopia of the avant-garde. The film therefore manages to help understand both Parallel Cinema’s indebtedness to avant-garde aesthetics and its subversive potential.

The Cruel Illness of Men consists of ten minutes of black-and-white montage scenes, without obvious consistency in narration. Accompanied by an ominous vibrating drone sound later recognizable as an oboe, it starts with an anonymous woman typing rapidly on a small machine, introducing one of the film’s main concerns: alienation. Depictions of collective power in early avant-garde as well as Socialist Realist art are replaced with physically separated men and women who follow their rigid work instructions all by themselves. A series of shots of a grey and foggy industrial landscape locates the scene in a post-human, dystopian environment. A single man is walking obliquely towards the camera while the industrial background dissolves into an ornament of tubes. He passes brick walls, a construction crane, and a line of pillars alongside railroad tracks without encountering anyone but a stray dog.

The depiction of architecture represents the motif of repetition in an almost existentialist way, as if there were neither a beginning nor an end to this grim journey. The film cuts to a bandaged person being thrown out of a heavy steel door by a man in a lab coat. The door is shut as the semi-human creature falls to the ground, presumably soon to be found by the dog. Meanwhile the young man is still wandering around. What follows is an uncanny montage of Soviet realia, documentary as well as narrative footage from home videos, movies, and television. The assembled footage presents contrasting concepts of the masculine and the feminine.10 Scenes of Soviet soldiers, sailors and construction workers, marching Nazis, and footage of war and destruction vividly portray the archetype of violent manhood. They alternate with innocent scenes of happy families, a girl in a bikini running into the sea, a wedding ceremony, school kids, or women playing the violin. The metaphors of masculinity can be emphasized as the more interesting side of this duality and clearly predominate the sequence; in fact, the reflection of the feminine just seems plainly stereotypical and dull. As Alaniz rightly notes, there’s “little to embrace”11 in Necrocinema from a feminist perspective. A link between masculine violence and homosexuality is vaguely introduced when scenes of soldiers and bombings are intercut with a shot of men forming a scrum (a rugby formation during which the players’ bodies are tightly interlocked).

Before commenting on the film’s most notorious scene, I want to shift attention to a small, recurring detail. Throughout the found footage sequence, close-up shots of a young man with dark hair appear, who resembles the man we’ve seen in the beginning. The man gazes straight into the camera. This seems kind of odd, given that the rest of the material’s main effect is to create a bleak atmosphere, which results in a generally distanced viewing experience. The young man, on the other hand, becomes recognizable and somehow relatable, introducing a glimpse of psychological undertone, almost empathy, into the work. On the one hand, he is depicted as an individual resisting the anonymity and alienation surrounding him. On the other hand, he represents a generation influenced by these images. Through the montage of the face of the young man and Soviet realia as the visual discourse of a certain time, the viewers are urged to connect both in a meaningful way.

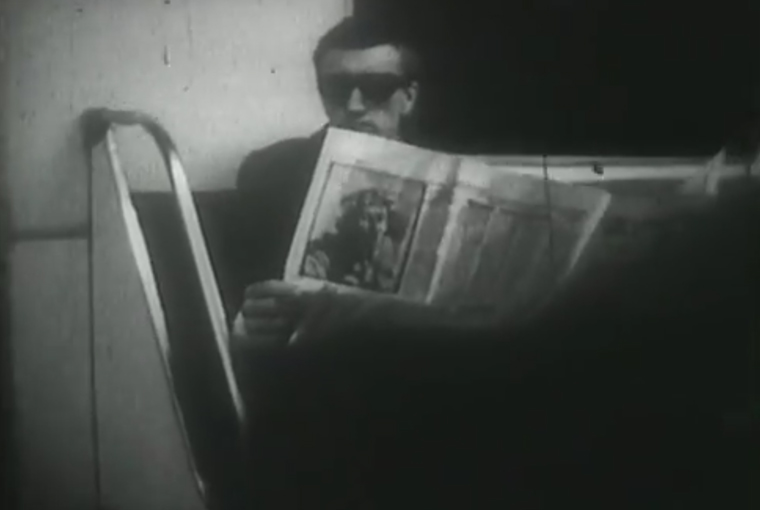

The same young man (or at least a similar looking guy) reappears in the next and final scene which takes place on a subway train. Two men in suits sit to the left, one of them absorbed in a newspaper, the other one facing the young man. After a few uneventful moments, the well-dressed man starts to harass the young guy and prevents him from trying to escape. This results in a disturbing rape scene, happening just seconds later on the floor of the train. At the same time, the other guy witnesses the event in awe while masturbating behind his newspaper which “rattles comically to his movements.”12 His eyes are hidden behind black sunglasses. The rapist puts his clothes back on and turns to the train’s door just like the newspaper guy. Both wait to exit the train at the next stop as if nothing had happened. The protagonist lies on the floor motionless, a tear running down his otherwise frozen expression, looking “almost corpse-like.”13

Particularly notable is the film’s unbalanced structure regarding the cinematic methods of dialectical montage on the one hand, and conventional continuous editing (like in the final scene) on the other. In relation to the whole film, the final scene occupies almost a third of the runtime, undermining what we have seen in the first six minutes. The first part of the film introduces a dystopian take on Eisensteinian montage, which in its very form was occupied with progress, the post-revolutionary future, and a conscious audience. The reference to this type of montage is especially visible in the found footage scene, where association is key to understanding. In the second part, on the other hand, the Aleynikovs take Eisenstein’s notion of attraction literally, albeit in a dark and perverted way.

Based on Hegelian and Marxist materialist theory, Eisenstein created his concept of the “montage of attractions”14 in the early 1920s. Eisenstein defines attraction as follows: “[…] any aggressive movement in theatre, i.e. any element of it that subjects the audience to emotional or psychological influence, verified by experience and mathematically calculated to produce specific emotional shocks in the spectator in their proper order within the whole. These shocks provide the only opportunity of perceiving the ideological aspect of what is being shown, the final ideological conclusion”.15 While Eisenstein had argued that the essential function of filmmaking is to activate a specific audience reaction through montage, the Aleynikovs want their viewers to endure the horror of violence and alienation. Furthermore, the film already anticipates its audience’s reaction: the newspaper voyeur in the subway scene functions as a placeholder for the viewer. He is an observer from the outside, refusing to intervene in the violent act.

The Cruel Illness of Men refers to Eisenstein’s definition of shock in three ways: firstly, through rapidly cut footage that urges us to associate and reflect, secondly, regarding its horrifying content, and finally, by implicating the viewer as a voyeur. Until the rape scene, the nihilism of radical emptiness and hopelessness is only suggested in more or less metaphorical terms. As the film moves on, one can no longer escape the literality of the shock moment. Viewers are forced to reflect on their own position in relation to the victim, the perpetrator as well as the voyeur. It is through this blatantly crass depiction that the audience is either asked to empathize, or confronted with its lack of empathy and therefore with its own perverted perspective. In adapting these avant-garde practices, as well as an iconography of (factory) work, the film reflects on the historical disappointments which led to the pessimistic worldview of Parallel Cinema. More precisely, it presents a link to an unredeemed promise of Socialism – the “stated aim of creating a classless, egalitarian society”16 – which was articulated both in avant-garde cinema and Socialist Realism.

To grasp the cultural situation of the late 1980s, José Alaniz refers to the late Soviet era as a “world of death,” following Ilya Kabakov’s text On Emptiness. Alaniz describes this period as “drained of transcendent meaning, a utopia gone to rot, where all is negative energy, a social living death.”17 The generation of the Aleynikov brothers grew up in this paradoxical situation, where, on the one hand, the Soviet state would still be experienced as “eternal,” and on the other, as Viktor Mazin puts it, “as more dead than alive […] evidenced by the gerontocracy, the death of one general secretary after another, the stagnation in the economic sphere, the negligible number of adherents to the ruling ideology, the absence of any sort of collective enthusiasm, and the demise of the aesthetic principles of Socialist realism.”18

These dogmatic principles of the “ideological transformation and education of workers in the spirit of socialism”19 are clearly negated in The Cruel Illness of Men. There is no euphoric praise of “strength, stability, and contentment”20 in Soviet society, but the opposite. The dissonance between reality and mass media becomes blatantly clear when the grimness of the wasteland is juxtaposed with found footage of happy families, kids and sports, revealing the absurdity and emptiness of the latter. In other words, these images “act as signifiers pointing to no actual referent.”21 The ideological picture of the state as a productive force during the Brezhnev era of stagnation22 is reflected in the factory as an empty and uncanny place, a ruin of a long-gone past. The only work taking place in the Aleynikovs’ factory is some kind of strange human experiment, an absurdist exaggeration which undermines their artistic approach as a nihilistic joke.

At this point, can there be a clear answer to the question whether the film holds a critical, or even utopian, potential? The main concern of this essay is to reflect on the specific form and its effect on the audience. To that end, “certain modes of spectatorship and of viewing” are more important than what is represented in the image. If we shift our attention to the contemporary viewer as the third and main element in montage theory, the shock produced by the “the spectacle of agony and pain” shown in the subway scene has an “affective impact the beholder cannot possibly escape.” Unlike the defeated victim on the subway floor, the viewer gets to experience “the real of our corporeal existence as it comes into view only where it is caught at its limits”.23 For contemporary viewers from a generation that was “ripe for suicide” and characterized by its “aggressiveness, despair, loss of stable moral values, and loss of affect”,24 the confrontation with the brutalized corporeality of the victim holds a distinctive significance. In this context – a reality experienced as an eternal void, a state of constant apathy –, the film extorts a physical and emotional reaction from viewers in order to make them feel alive again.

The film’s potential of transcending the mere surface of representation clearly lies in its radical approach towards depicting emptiness. Through the specific construction of the film, namely the structuring of different montage methods and the (negative) inclusion of spectatorship, another world becomes imaginable. The grotesque abstraction of social reality as a factory wasteland inhabited by undead creatures and antihuman rapists destabilizes the seemingly eternal experience of senselessness – in their alienated state, they become the subject of interpretation, reflection and discussion.25 When thinking about the role of death and violence in The Cruel Illness of Men and its entanglement with montage, Walter Benjamin’s notion of allegory comes to mind. According to Benjamin, “criticism means mortification of the works. […] Mortification of the works: not then – as the romantics have it – awakening of the consciousness in living works, but the settlement of knowledge in dead ones.”26 Here, we find the idea of “a preservation in which destructive and utopian impulses are held in tension.”27 By resorting to formal fragmentation and a brutal subject matter, The Cruel Illness of Men exposes itself to being criticized, becoming more than pure spectacle.

However, as much as violent art films like The Cruel Illness of Men have to be seen in their respective contexts, the discriminating and harming potential of certain depictions should not be overlooked. Basically meant as “a riposte to Soviet archetypes of manhood,” the film nevertheless operates with homophobic stereotypes “of the Russian homosexual as depraved, ‘alien’ and potentially violent”28. The myth of the Soviet hero as the epitome of “hypermasculinity”29 can apparently only be subverted through the brutal violation of a man’s body through homosexual rape in a public space. It speaks volumes that this is presented as the ultimate act of humiliation. More academic works with a focus on the specificity of violence and homoeroticism ever-present in Parallel Cinema and Necrorealism are a necessary addition to the discussion around the legacy of these films today.

References

- 1.See Graham, Seth (2001). Necrorealism: Contexts, History, Interpretations. Pittsburgh: Russian Film Symposium ; Alaniz, Jose (2003). Necrorama: Spectacles of Death and Dying in Late /Post-Soviet Russian culture (Order No. 3121382). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (305339035). Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/docview/305339035?accountid=10957 [Accessed on October 30 2020]; Berry, E., & Miller-Pogacar, A. (1996). A Shock Therapy of the Social Consciousness: The Nature and Cultural Function of Russian Necrorealism. Cultural Critique, (34), 185-203; Mazin, Viktor (1998). Kabinet Nekrorealizma: I͡Ufit i Kabinet. St. Petersburg: INA Press. Often there is no clear distinction between Parallel Cinema and Necrorealism, except for geography, as Necrorealism is associated with Leningrad.

- 2.Alaniz, Graham in: Graham 2001, 8.

- 3.Berry, Miller-Pogacar in: Alaniz 2003, 94.

- 4.Ibid., 87.

- 5.Baumbach, Nico (2016). Act Now! or For an Untimely Eisenstein, In: Kleiman; Somaini. Sergei M. Eisenstein: Notes for a General History of Cinema. Amsterdam: University Press: 209-307, 305.

- 6.Eisenstein in: Ibid, 305.

- 7.Ibid., 299.

- 8.Epstein in Berry, E., & Miller-Pogacar, A. (1996). A Shock Therapy of the Social Consciousness: The Nature and Cultural Function of Russian Necrorealism. Cultural Critique, (34), 185-203, 186.

- 9.Ibid., 186.

- 10.See. Alaniz, Graham in: Graham 2001, 12.

- 11.Alaniz 2003, 143.

- 12.Alaniz 2003, 93.

- 13.Ibid., 93.

- 14.Eisenstein, S., & Gerould, D. (1974). Montage of Attractions: For Enough Stupidity in Every Wiseman. The Drama Review: TDR, 18(1), 77-85.

- 15.Eisenstein, Sergei, Richard Taylor, und Michael Glenny (2010). Sergei Eisenstein, Selected Works. London; New York: I.B. Tauris, 34.

- 16.Drew, Thomas (2017). Necrorealism: Absurdity and the Aesthetics of Social Decay in Late-Soviet Russia. Retrieved from: https://studenttheses.universiteitleiden.nl/handle/1887/52276 [Accessed on October 30 2020].

- 17.Alaniz 2003, 90f.

- 18.Mazin in: Alaniz 2003, 2.

- 19.Tertz, Abram (1960). On Socialist Realism. New York: Pantheon, 24.

- 20.Drew 2017, 26.

- 21.Alaniz 2003, 124.

- 22.Sakwa, Richard (1999). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union 1917 – 1991. Routledge London, New York.

- 23.Buch, Robert (2010). The pathos of the real: on the aesthetics of violence in the twentieth century. Rethinking theory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 16f.

- 24.Dobrotvorskaya in: Berry, Miller-Pogacar 1996, 196.

- 25.In the Brechtian sense of Verfremdung.

- 26.Benjamin, Walter (2003). The Origin of German Tragic Drama. London ; New York: Verso, 182.

- 27.Gelley, A. (1999). Contexts of the Aesthetic in Walter Benjamin. MLN, 114(5), 933-961, 943.

- 28.Alaniz 2003, 94.

- 29.Ibid., 123.

Leave a Comment