Humanism & the Bomb

Ion Popescu-Gopo’s A Bomb Was Stolen (S-a furat o bombă, 1961)

Vol. 24 (December 2012) by Konstanty Kuzma

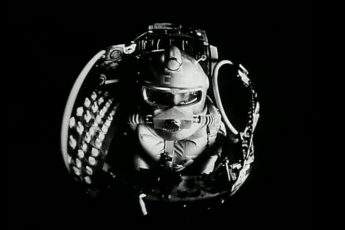

A clueless man walks across a deserted strip of land when a helicopter turns up from nowhere and begins racing him. A few moments later, 3 camouflaged cars appear on the horizon; a dozen soldiers step out, and the man is ceased… No, this scene is not from Hitchcock or a Bond film. It’s the opening sequence of A Bomb Was Stolen, a 1960s Romanian sci-fi spy film by Ion Popescu-Gopo, a Romanian animator who won the Short Film Palme d’Or in 1957. A Bomb Was Stolen – which also visited the Croisette – marks Gopo’s first attempt in live-action film, but with its naive moral, absurd plot, slapstick, and complete lack of dialogue it, too, strongly resembles classical animation.

In Gopo’s film, two criminal gangs fight over the possession of an atomic bomb in a dystopian, futuristic city. As fate wants it, the bomb soon ends up in the hands of a man who wants to know nothing about it (in fact, he doesn’t until the very end), but who finds himself in the middle of the relentless rivalry regardless. Escaping from the police, the robbers leave the dangerous artifact behind; our innocent protagonist (once again, wrong time, wrong place) picks up the bomb and tries giving it back to its supposed owners, an attempt which proves unsuccessful – luckily. Gopo stretches this simple plot over 72 minutes, a running time that seems justified with regard to the requirements for feature length, but not when it comes to the material. The film’s pace jumps back and forth from slapstick mania to romantic drama – a movement that might work if the film was more diversified. But the middle part merely seems like a variation on the same scenes played out over and over, a pattern that grows tiresome after a while. Indeed, A Bomb Was Stolen is a historical curiosity, no cinematic gem, and it is no surprise that recent examinations approached it from a historical perspective rather than a cinematic one.

Interestingly though, Gopo himself is quite explicit about the cinematic tradition in A Bomb Was Stolen. Besides abundant quotes and references (Chaplin, Keaton, Tati, Godzilla etc.), he even lets his protagonist visit a cinema to illustrate its ambiguous powers. Once there, he first studies our nameless hero’s reactions to a horror photo story from fear to ecstasy. Then, the protagonist is mistaken for a cannibal when he tries to help a lost child, and the child’s parents spot them next to the poster of a child-eating monster. Cinema can manipulate, and Gopo does so himself, for instance in his love scenes: whereas the criminals enjoy the striptease of a cowgirl in a dubious establishment, our hero falls in love with a uniformed bus conductor. To draw the viewer to the “good side,” Gopo thus uses music, a Chaplinesque dream sequence and his very best Mise-en-scène to win us over; the criminal on the other hand gets a shot-reverse-shot exchange, with the object of desire (the stripper) carefully concealed from the eyes of the audience.

For a film on “the bomb” from behind the iron curtain, Popescu-Gopo’s film appears strikingly unpolitical. Although there are jabs at American culture here and there, it’s cops and robbers mostly. This may in part be due to the emerging National Communism in Romania: during the 1960s, the Romanian Communist leaders (first Gheorgiu-Dej, later Ceauşescu) sought to de-Stalinize the country, an effort that also allowed artists to deal with political subjects more freely (of course, Ceauşescu himself soon reverted this tendency by reaffirming the role of the party, thus introducing two decades of “neo-Stalinism”). The film has been put in the context of Cold War films, but it’s mainly a yearning for humanism. Gopo’s main goal is not to weigh capitalism against Communism. It’s to show that even in the gloomy setting of his sinister metropole, heroes rest in ordinary men. Gopo’s film teaches us that we should refrain from strippers, deception and violence. That, it seems, is a moral one can attempt to comply with in any system of the world.

Leave a Comment