Causes-turned-reasons

Jan Jakub Kolski’s Pornography (Pornografia, 2003)

Vol. 46 (October 2014) by Konstanty Kuzma

Pornografia is probably not the novel that would first come to mind if one sought literary material fit for a cinematic adaptation. With a perplexing structure, opaque characters and Witold Gombrowicz’s signature inclination to counter our intuitions, it demands care and perseverance in fighting confusion on the one hand, and boredom on the other (at many points, the narrator’s struggles with his own conjectures and desires grow tiresome indeed) – this is not the book you want to buy your mom for Christmas. Both Gombrowicz and Jakub Jan Kolski, the man who accepted the challenge and turned words into images, share such misgivings and have described the novel as being uncinematic1. Whether cinematic or not, Kolski’s adaptation reflects his views of cinema being a medium that, unlike literature, demands reasons for actions. While that is a legitimate approach to cinema shared by myself to some degree, it clearly turns against Kolski in approaching Gombrowicz’s book, which is very much about causes, and not at all about justificatory reasons.

The novel takes place in Poland during WWII, although the historical setting is often on the verge of being forgotten: “Whatever the meaning … of war, of revolution, violence, debauchery, degradation, despair, hope, struggle, fury, screaming, murder, slavery, disgrace, lousy dying, of cursing or blessing… whatever was the meaning, I say, it was too weak to break through the crystal of this idyll, and this little scene, long after its time, remained untouched, it was only a façade…” (p. 17)2. Witold and Fryderyk, roughly midlife artists, seek refuge at Hipolit’s house, a landowner and acquaintance who offers them agreeable shelter outside of Warsaw while the war rages on. This spatial shift away from war to “idyll” is not complete – members of the Polish Underground Army and Nazis will keep reappearing in the story – but it sets the tone of the novel from the very beginning. Witold, who narrates the story, becomes infatuated with Henia and Karol, two adolescents who are at first merely acquainted with one another, but soon turned into companions in intrigues and betrayals orchestrated by Witold and Fryderyk. Their perverse goal is to exploit Henia and Karol first out of sheer curiosity nurtured by erotic undertones, then to reach concrete but equally contemptible goals like killing Siemian, a Polish officer gone mad, or destroying the relationship between Henia and her substantially older fiance Vaclav – to Witold and Fryderyk, the planned marriage between Vaclav and Henia betrays the natural bond between her and Karol and is to be averted at all costs.

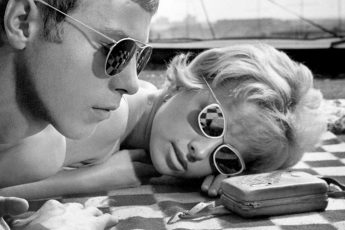

In stark contrast to the novel’s sly build-up, Henia enters Kolski’s film with cinematographic and verbal grandiloquence – a pathetic introduction by her father (“here is Henia, my beautiful girl, the most beautiful in the world!”) is chaperoned by the fixated gaze of Fryderyk, Witold and the camera. No viewer could overlook Kolski’s order to start finding this young woman attractive, and so one has no trouble understanding why Fryderyk and Witold do. Unable to initiate the viewer in the duo’s illicit perversion, Kolski objectifies their desires, thus stripping them of any peculiarity; Henia and Karol are the protagonists of erotic games because the two are already horsing around without external involvement (e.g. when she playfully nudges him in front of Witold and Fryderyk), – they are erotically loaded, raw material waiting to be molded. On the contrary, in Gombrowicz’s Pornografia, Witold, the narrator, is in constant doubt about the objectivity of his erotic fantasies – the first time that he makes a connection between Henia and Karol, it is merely in his imagination:

Fryderyk? Did Fryderyk know about it, or see it, did his eye catch it too? […] Henia walked ahead of me, her back and her little nape still a schoolgirl’s, and this is what came to mind, and when it did, it took hold of me so strongly – it linked up with the other neck so efficiently… that I suddenly understood, easily and without effort: this neck and the other neck. These two necks. The two necks were… (p. 24)

What ensues is an examination of “the awkwardness of these metaphors” (p. 24) and a repeated questioning of the supposed match between the two bodies (p. 25f.). Gombrowicz does not concentrate his efforts on establishing that Henia and Karol are in actuality a good match. Both are described in general, almost clichéd terms – Karol as a brute feeling “”boyish” love in its total degradation” (p. 31), Henia as “nothing but a captivating force” (p. 82); in confidential conversations with Witold, they both reveal having no particular interest in each other. The reason that Witold and Fryderyk are obsessed with the young couple-to-be is perversion, boredom, perhaps a yearning for distraction, not qualities intrinsic to Henia or Karol. In many ways, it is not the desire itself, but the dialectic of Witold’s imaginative “pornography preying on them” (p. 34) vs. the gradual unmasking of Fryderyk as his secret companion that is the leitmotif of the book. Constantly, Witold struggles to overcome epistemic barriers:

I didn’t really know him [Fryderyk], I couldn’t have known him, I didn’t know what and how things had formed him, he was as unfathomable as this landscape – familiar yet unfamiliar […] (p. 67)

Later on, the magical match between Henia and Karol is inverted when they join forces with Fryderyk and Witold to kill the crazy officer Siemian (another abrupt, somewhat intangible twist in the story). Suddenly it is the harmony of young and old that fascinates Witold:

Who knows, perhaps one of mankind’s darkest mysteries – and the most difficult – is actually the one that pertains to this “uniting” of age groups – the manner and course by which youth suddenly becomes accessible to older age and vice versa. (p. 131)

Where throughout the novel it was the single desire of Fryderyk and Witold to avert “betrayal” (p. 56), to realize the imaginative match between Henia and Karol – of “youth” (p. 105) -, Witold suddenly begins to see meaning in a cross-age matchup. This is because Fryderyk’s and Witold’s irrational desires are just as crucial to the novel as the perceptual perspective that generates them. From the beginning, the narrator is obsessed with ordinary situations that seem strangely peculiar to him – is it because of Fryderyk, or the war (p. 14f.)? In the end, such rationalizations and the fact that many of Witold’s imaginative constructions turn out to be justified, are secondary. Gombrowicz is after things “expressing what words did not encompass” (p. 98), “hidden meaning” (p. 77), “”otherness”” (p. 94), “a third presence of an unknown quality, something intangible yet unrelenting” (p. 157). The novel mystifies, whilst Witold and Fryderyk desire – and where there is desire, there is no need for rationality to motivate action.

Kolski disregards this mantra by inventing a moral alibi for the duo as well as a background story for Fryderyk (which both increases his and erodes Witold’s role in the narrative). Since in the film, Henia and the coeval, lascivious servant Weronika make their yearning for sensuality fully explicit vis-à-vis Fryderyk, the male lead duo merely reciprocates independently existing desires – in full accordance with the cliché of a Polish gentleman, Fryderyk even refuses an open invitation to sex. Kolski’s Fryderyk is also a former jail mate at Auschwitz and troubled by the tragic fate of his daughter, while Witold refrains from blowing the cover of Jews hiding at Hipolit’s house. Can we be angry at Fryderyk and Witold for wanting to screw around a bit? That Kolski raises this question shows how poorly he understood Gombrowicz, who stresses in an introductory statement published together with Borchardt’s translation that he never experienced wartime Poland, or how he did not intend to be critical of the Underground Army – the question of guilt simply does not apply. Pornografia is not about the Second World War, and neither is it about objective desires. It is about a historically contingent time when everything was allowed and much of the worst was brought out in humans (yes, even in Poland). A time that fits the kind of mindset revealed by the novel’s narrator: one driven by desires to see and experience more than is feasible or permissible. Ironically, Kolski approached the novel with this very mindset. Guess what happened.

Leave a Comment