Melodies of Town and City

Otar Iosseliani’s Pastorale (Pastorali, 1975)

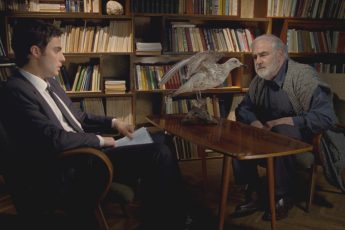

Vol. 57 (September 2015) by Konstanty Kuzma

In an early scene of Otar Iosseliani’s Pastorale, which takes place in a remote Georgian village, a group of local children flock to a rehearsal of a quartet of musicians who’ve travelled to the countryside to practice. The cheerful scene, which has curious and loud children turn inquisitively silent at the sound of music, is a rare instance in Iosseliani’s work in which urban and rural life appear reconciled, mutually appealing even, and in which the Soviet myth of the USSR as a state which can bridge seemingly unbridgeable divisions appears vindicated. It’s a set-up which also recalls the famous German legend of the ratcatcher, Pied Piper of Hamelin, who is said to have stolen 130 children from a town which refused him pay for ridding it of a rat plague. According to the myth as documented by the Brothers Grimm, the ratcatcher’s only weapon was a flute, with which he was able to entice both the animals that plagued the city, and the children which gave sense to it (a narrative which inspired frequent comparisons to Hitler).

Of course, the lead quartet in Pastorale pursues no such evil motives. Both their strict rehearsal routines and their interest in local songs suggest a genuine interest in music, and they make repeated attempts to bond with the locals. Yet rural life follows its own logic which is seemingly impossible for strangers to penetrate – quarrel, alcohol and boredom fill the space in between tough routines that seem eternally more taxing than the musicians’ leisurely practice sessions. Even Gela, who’s half-host and half-guest at the village, struggles to shake off the alien air that surrounds him and his friends. When his companions leave early from a local feast, he loses his temper and accuses them of rudeness in an apparent attempt to mimic the edgy ways of the locals. In this clever dramatic set-up, music plays a symbolical role which points to the stark differences which divide city and town, adumbrating scenarios that are not all that remote from the one recounted about the Pied Piper of Hamelin.

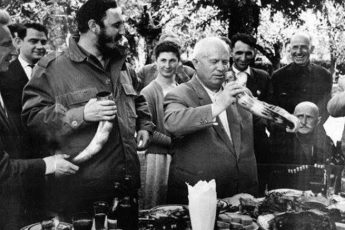

Typically for Iosseliani, the film’s opening forms a biting contrast to what shall follow. Set in a nameless office building whose acoustical backdrop is one of buzzes, clickers, footsteps and paper-rustling, the sequence briefly depicts a grumpy and taciturn boss’s lunch break. No harmony or melody is emitted during this 2-minute scene which forms a succinct reminder of the pitfalls of urban life, most notably its super-individualism, which may be a principal reason for the scene’s lack of music. Against this opening, the travelling quartet is not a group of anti-heroes who are waiting to be moralized, but friends who themselves appear to share a minimum of the communitarian spirit that seems necessary to form a quartet. What they embrace while travelling to the countryside is not just the right setting to work in, but likewise the very collectivism whose powers Iosseliani is seeking to unveil. Undoubtedly, it is here that Iosseliani sees the hidden powers (and symbolism) of music. In Georgia in particular, where folk music is infamously polyphonic and thus inherently super-individual, music is a social phenomenon that is often performed ritually at the table when people meet to drink and feast.

Thus in Pastorale we find villagers playing and listening to music while sharing a drink, or when gathering to meet their guests. The visitors, on the other hand, tend to practice in isolation, and listen to LPs – of local folk songs or the Foxtrot, – whenever they feel like it. Still the latter not only form a quartet, i.e. a mini-collective, but often seem like the more civilized lot, like when their hosts start a fight after their neighbors start building a house without prior notice, or when the local drunkards brawl in the town center. Interestingly, state officials here act as mediators who are able to reconcile quarrelling parties, suggesting that Iosseliani’s stance, notably his collectivism, may be compatible with Soviet ideology, but pro-party nods are clearly overshadowed by criticism, albeit cautious, of collectivization; industrial machines (for crop dusting, plowing and transport) are ultimately the biggest hazards to peace in the village and lead to notable tensions. If the villagers are reasonably close to genuine communitarianism and the musicians are close to adopting it, bureaucrats seem to have no more than a nominal proximity to Iosseliani’s ideals. After all, aren’t productivity demands the root cause of tensions among the villagers?

Pastorale, perhaps like rural life itself, seems non-linear and eternal, and it is easy to get lost in the loose dramaturgy of the plot. Most of the scenes have an illustrative rather than a narrative function and lack a clear positioning on the topics raised. After the main dynamics of the film have been established – there is e.g. the suspense between ex-local Gela and his former village, or between the neighbors who are quarreling over the newly built house -, the film contrasts the tough routines of the village with the superficial self-entertainment attempts of its visitors. It is here that Iosseliani cleverly establishes a motif that resembles that of the Pied Piper of Hamlin. Towards the film’s end, the musicians include a local girl in their routines, and even make her join some of their musical habits. She learns to sing a simple song on the piano and shares her LP collection with a young, attractive musician from the group. When the quartet leaves, she is given a flute and asked not to forget about the time they spent together. Finally, in the very last sequence, Iosseliani juxtaposes her wandering through the empty rooms where the guests were staying (while she listens to an LP) with the homecoming of one of the girls from the quartet. The latter scene is shown from the perspective of the musician’s father, who returns home to the sounds of the cello, asks his wife “has she arrived?”, and sits down wordlessly – without greeting or even seeing her daughter -, in an adjacent room to listen to her play. Such isolation may be the fate of the village girl if she lets herself be enticed by the promise of city life…

Leave a Comment