Down the Rabbit Hole

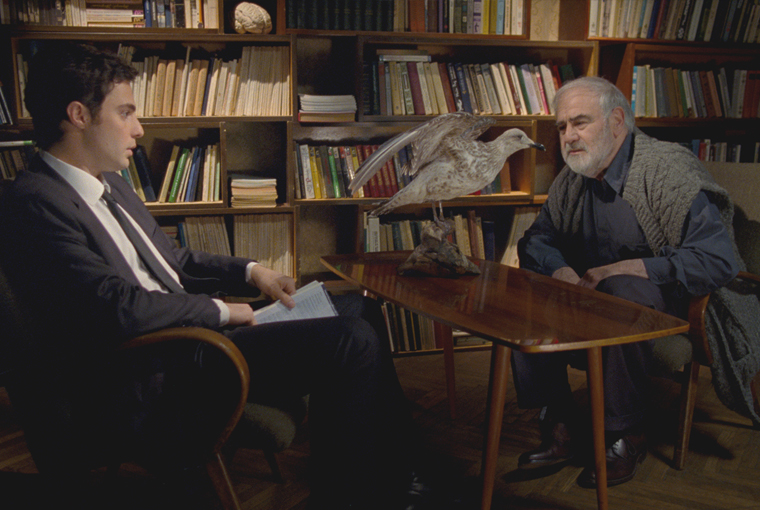

Zaza Rusadze’s A Fold in My Blanket (Chemi sabnis naketsi, 2013)

Vol. 26 (February 2013) by Konstanty Kuzma

A Fold in My Blanket, one out of two Georgian films selected for this year’s Berlinale, sets out far off from reality. The protagonist of the film Dimitrij (Tornike Bziava) enters a cave, and, accompanied by odd sounds matching the magical situation, is seen opening a door. Cut to an office building where Dimitrij hopes to find a job, and we’re in modern-day Georgia. Zaza Rusadze takes us down the rabbit hole, which is just as much the setting of his film as reality is. The first-time director adopts the “reality vs. illusion” approach, arguing (in a rather conventional manner) that the boundaries between reality and fantasy are porous. The scarce plot revolves around Dimitrij’s struggles to deal with a reality he can’t identify with, and, late into the film, around his attempt to free his childhood friend Andrej (Tornike Gogrichiani) of his legal troubles. In between, Dimitrij visits nature (the only sane place on earth, we are told, and the one where phantasy is within reach), meanwhile meeting an array of characters in the “real world”: relatives, friends, neighbors, and co-workers; roles that feature some established Georgian actors who are unable to help the generally mediocre acting.

Politically and socially speaking (we are at the Berlinale after all), Rusadze is ambiguous. Clearly, the film is set in a Georgia at crossroads, as public buildings around Dimitrij’s anonymous hometown are gradually covered with political flags and banners, while the many scenes acted out in Russian refer to post-Soviet times (due to the difficult diplomatic ties between Georgia and Russia – the low-point was a war in 2008 -, the Russian language’s popularity among Georgians is in fact rapidly decreasing). But the film doesn’t develop any of these references, and so its political and social ambitions remain as blurry and vague as the homoerotic tension between Dimitrij and Andrej. While we learn quickly that there is something bugging our protagonist, none of the problems Dimitrij faces are dramatically unsettling: there is a drunkard beating up an old man (which, on the terms of Rusadze’s realist/surreal universe, may not even have happened), mean employers, and a crazy aunt. Throughout the film, Rusadze fails to develop a setting into a stance, and hence Dimitrij’s fantastic excursions do not translate into a proper message. The film is a hike in the forest, not a trip to Georgian reality.

Dimitrij’s odd encounters keep accumulating, and yet attempts to grasp a discernible plot line are in vain. The short spanning time (70 minutes) was wisely chosen, as Rusadze’s fondness for spacious locations and well-framed landscape shots creates a ghostly atmosphere that is enjoyable, but devoid of magic powers: unfortunately, the lack of an emotional or narrative tension remains too great a challenge to tackle with visuals alone. There is a scene in the middle of the film when Dimitrij asks Andrej to pull himself together: “Haven’t you looked at yourself?” Unlike Andrej, Dimitrij is vigilant. He acknowledges that the corrupt and monotonous reality he is facing should unsettle him. But like Andrej, he, too, is unable to come up with a satisfying solution, and so he seeks refuge in nature and fantasy, incapable of helping Andrej to tackle his problems. Rusadze, then, seems to face the same dilemma as Dimitrij: he rejects the reality he is confronted with, but is unable to provide us with an alternative one that is appealing enough to enchant us. Here is a young director who knows what he wants, but doesn’t seem to have figured out how to get it yet.

Leave a Comment