Adventures in Time and Space

Bobo Jelčić’s A Stranger (Obrana i zaštita, 2013)

Vol. 26 (February 2013) by Colette de Castro

Like many a theater director before him, Bobo Jelčić is breaking into film. A Stranger, a film about being foreign to your own city, is the result of this gamble. After the death of a close Muslim friend, Slavko is plunged into a heated debate about whether or not to attend the funeral. As a Croat, he would usually not venture into the Muslim part of the city, let alone to attend their ceremonies. But his wife and friends want him to go, and he finds himself faced with a moral and spiritual dilemma which threatens to cause political problems as well as problems on the home-front.

As in Children of Sarajevo (2012), this film portrays the lives of everyday people in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Like Aida Begic, Bobo Jelčić chose to film in his hometown, here the city of Mostar, one of the largest in Herzegovina. In both films, there is a proliferation of over-the-shoulder shots. Perhaps they serve to remind us of the division between groups of people which is so pronounced in these war-torn cities. The importance of point of view is pivotal, even twenty years after the war.

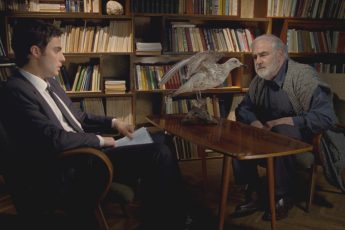

“I make movies to demonstrate a story in time, because I think theater is a story in space,” the sometime theater-director stated in an interview. We can easily imagine what Jelčić means by ‘a story in space’, 3D cinema is no match for an actor who can approach, touch and physically play with the spectator. We only have to look to theater traditions such as Antonin Artaud’s theater of cruelty to remember that real-life performances can reach us in ways that a cinema screen can (probably) never recreate.

But what exactly does Jelčić mean by ‘a story in time’?

It could mean that the story takes place over a long period: in the film, we see Slavko’s friend dying in the first scene, then his family is preparing for the funeral in the next. Surely there were days and hours between these two events? But this perception of the passage of time can be created almost equally well in the theater, calling for cleverly placed lines about time passing, rather than spectacular sunsets.

Maybe a story in time is more about settings. We contemplate the permanence of the old brick walls in the home of Slavko and his wife. Those walls have surely seen things that no theater set has expressed. The glimpses of the city, the cemetery and the houses all give us a sense of time that isn’t so easily created in the theater. The camera follows Slavko down the long streets of his town, so we feel a strong sense of history. Is this the ‘time’ of which Jelčić speaks?

It’s most likely that Jelčić is talking about the kind of time that we all need and don’t have, time to correct imperfections. In cinema this is possible: in live performances it is not. It seems as though some of the most honest moments in cinema are born from acting that has built up momentum through continuous filming; the kind when camera battery is running out and every second is crucial, rather than stale acting. Of course, we can’t know what exactly goes on in editing departments, but why is it that long scenes or monologues often seem so much more natural than short conversations between characters?

Among others, this is something that disturbs me about recent Woody Allen films. It’s as if the character’s lines have been learned so well, and then unlearned so carefully that we don’t know who is saying them. In these high-budget films, the conversations are forced, even though they have been carefully worked on so that they seem natural. The echo of the director’s voice yelling ‘cut’ over and over again can almost be heard through the celluloid. The strain of a thousand takes can be seen on the actors faces (despite the make-up). Low budget films on the other hand, in which the producer can’t afford to be too picky, seem so much more real. The urgency of getting a good shot makes for convincing rhythms. An Episode in the Life of an Iron Picker, that was also screened at the Berlinale this year, is a good example of this. A biographical story, filmed with non-actors who really lived the events, it’s very easy to get caught up in their story. In A Stranger, while the film is not perfect, there are also many moments of believable exchanges.

This film is therefore successful in terms of acting, which is not to say it is successful in other ways. There is an overabundance of friends names – often characters who we never meet. While this flow of character references may be effective in Chekhov, it seems unnecessary here. The plot is rather clunky and the alternation between comic and tragic themes don’t work. The scenes where Slavko is struggling with petty administrative secretaries would have probably been quite amusing if we felt any affinity for him. In fact, Slavko, who has constant mood swings and suicidal tendencies, is too indecisive and weak for us to feel any real sympathy for him. His principal motives for being indecisive about the funeral seem to involve saving his own skin, and he seems to have no thought for other people.

That’s the problem with believable conversation: it’s fantastic to believe in an actor’s sincerity, but if the message isn’t coming across clearly, the point is missed. So we must look for the balance between belief and comprehension. If cinema is a ‘story in time’, then Jelčić should really use that time to elaborate a story and characters that are convincing.

Leave a Comment