The opening shot in Roman Balaian’s Flights in Dreams and Reality (Polety v sne i naiavu 1982), a film lauded as a “manifesto” of late Soviet culture, presents an upside-down view of its protagonist, Sergei Makarov, a chronic insomniac played by Oleg Iankovskii.1 The coding function of this inverted image is to, from the outset, locate Balaian’s narrative in a half-asleep, half-awake state. The scene’s dreamlike quality is underscored by Vadim Khrapachyov’s ethereal electronic music, which channels the dissonant synth soundscapes of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972) and Stalker (1979). The beginning of Balaian’s film, then, reenacts its title onscreen: Flights in Dreams and Reality. The viewer is unsure of Makarov’s metaphysical whereabouts. Trying to sleep, Makarov yearns to “deterritorialize” his subjectivity out of—vnye—his provincial apartment.2

Yet the pressures of ordinary life wrest him back into reality. The rumble of an oncoming train (another nod to Stalker) blaring state propaganda invades Makarov’s space. The industrial echo of state power intrudes on an otherwise private dwelling, impeding any possibility of imaginative escape. Makarov then rolls out of bed and heads to his desk. His workspace is littered with blueprints and protractors. The viewer infers that Makarov is an architect. He ignores his floorplans, however, to begin writing a letter to his mother. Yet he quickly abandons this idea for drawing a peculiar doodle only to crumple up the sheet of paper and toss it aside. Khrapachyov’s eerie music returns as the camera, handled by the well-known Ukrainian cinematographer Vilen Kalyuta, lingers on the wrinkled stationary, dwelling on its creased, distorted texture. This close-up of rumpled paper then suddenly repeats itself, whereupon its crinkly surface fills the entire screen. What to make of these intimate close-ups of paper discarded by a disaffected Soviet architect struggling to separate reality from fantasy in the twilight years of Soviet power?

The answer to that question begins several decades earlier in Soviet history, specifically in the years after Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953, which triggered a relatively brief period of sociopolitical liberalization popularly known as the Thaw (1956-65). Despite the optimism those years drew from events like the Cuban Revolution, Soviet space exploration, and greater artistic freedom, the Thaw eventually gave way to a conservative backslide in the late 1960s, a cultural refreeze, led by disgruntled Party apparatchiks. With Leonid Brezhnev at the helm, Soviet officialdom initiated a campaign of “de-de-Stalinization,” that is, a resumption of show trials, increased censorship, tedious state rituals, and a restored personality cult, all of which conspired to fuel what Mikhail Gorbachev famously called an “era of Stagnation” (1966-85), a period of cultural and economic stasis, morass. The canonical “start” of this era, if one were to pinpoint it, was the Soviet Union’s invasion of Prague in 1968 that stamped out, literally by way of tanks and artillery, a whole generation of utopic Eastern European visionaries who, emboldened by Stalin’s death, still genuinely held out hope for communism’s promise.

A consequence of this conservative backlash in Soviet society was the marginalization of architectural specialists, whose bold ideas had been shaped by the dynamism of the sixties and could no longer be accommodated by the state. Late Soviet construction, even more so than it already had, became a direct extension of the Party’s hidebound commitment to output and standardization. The legacy of Brezhnev-era architecture is defined by the monochrome, hypertrophied, and shoddy apartment complexes still dotting present-day Russia. The architectural profession, in turn, became a profoundly unappealing career choice for young talent starting in the late 1960s. Hence, by 1987, given the widespread abandonment of architecture by educated professionals in the 1970s, only 350 of the 500 chief architects in Russian cities had professional degrees, while over five-hundred Russian towns had no lead architect at all.3 Otherwise promising designers, in what one critic calls an “escape to design,” turned elsewhere to pursue their creative endeavors.4

These underground architects began exploring an alternative mode of spatial production,5 “an architecture of the catacombs,” whose projects were conceived as utopias unconcerned with their own materialization in the “stagnated” above-ground world.6 Their imaginative drawings mined the grammar of urban planning for the assemblage of wishful spaces hovering somewhere between imagination, history, and the dilapidated reality of late Soviet life. They rejected the gray, prefabricated models of the Soviet mainstream and projected a desire for alternative building materials: marble, sand, crystal, air, water, and glass—elemental, earthly, and everlasting materials, which could, they believed, facilitate experiences of metaphysical transcendence.

Whimsical and intentionally unbuildable edifices, such as City No. 2 (1981), Self-Erecting Prefabricated Playhouse (1983), Bulwark of Resistance (1985), performed an impermissible critical function in late Soviet society, a (meta-)architectural discourse that afforded designers an experience of psychic deterritorialization out of the stifling cultural atmosphere of late Soviet society.7 Such sketches became the ultimate form of artistic erring for disenfranchised design specialists like Yuri Avvakumov and Evgenii Ass and lent this quixotic architectural movement its nickname: “Paper Architecture,” a pejorative term originally deployed by Stalinist designers to denigrate the Constructivist experiments of the 1920s Soviet avant-garde.8 Their designs were just as impractical and fanciful—and crumpled just as quickly against the forces of politics and power.

The fantasies of the Paper Architecture movement, I want to suggest, also took hold in Stagnation-era film. The visual culture of underground Soviet design migrated onscreen. The motion picture emerged as a dynamic site of architectonics in the 1970s-80s, an elastic space on which to experiment with new spatial possibilities that afforded similar experiences of psychological escapism. The connection between moving images and architecture in late Soviet culture is not incidental. Theorizing cinema’s relationship to urban modernity in the early twentieth-century, Giuliana Bruno writes: “Moving along with the history of space, cinema defines itself as an architectural practice. It is an art form of the street, an agent in the building of city views. The landscape of the city ends up interacting closely with filmic representations […].”9 Cinema, a spatial art, is inscribed with an “architectural unconscious” that interfaces with whatever spatial milieu in which it is embedded. Late Soviet filmmakers similarly registered the dissatisfaction with the Brezhnev era’s built environment and articulated it via fantastical designs.

Let’s return, then, to Balian’s Flights in Dreams and Reality, a work with close-ups of literal paper that depicts a disenchanted architect fleeing into the recesses of his own mental fantasyland. When Makarov is kicked out of his apartment by his aggrieved wife, he wanders around his provincial city of Vladimir, a suburban topography that, as Balian’s film unfolds, slips ever further into the realm of surreality. After first staging his death with a melon, Makarov finds himself on a film set, arguing with Nikita Mikhalkov, a meta-filmic episode that draws attention to Flights in Dreams and Reality’s own fictitious construction. Makarov then wakes up with a black eye in a hay bale only to later spy on a teenager strangely dancing to electronic space disco. Balian’s film maps a chimerical geography in which Makarov struggles to distinguish fantasy from actuality. It is fitting that the longest take of Flights in Dreams and Reality is an image of Makarov dreaming aboard a train before he is escorted back home by a woman in a rickety tramcar, a contraption that recalls the handcar of Tarkovsky’s Stalker, another cinematic “flight” into surreal lands.

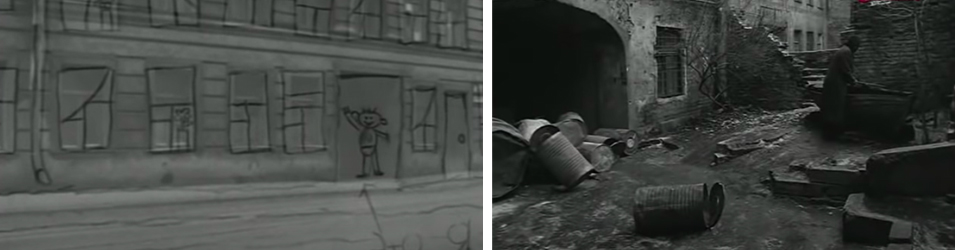

Makarov’s eccentric voyage concludes at his fortieth birthday party, where, after losing an arm-wrestling match, he again stages his own death. Shunned after he owns up to his stunt, Makarov pointlessly chases several young boys into an open field, where the bale of hay he encountered earlier reappears in duplicate and triplicate. This scenic enlargement is highlighted by the gradual amplification of the ugly doodle Makarov sketched in the film’s opening sequence. First seen in ink on the upper right-hand corner of a letter, then in graffiti on a brick wall, then in paint on a white tarp, Makarov’s doodle (self-portrait?), by the end of Flights in Dreams and Reality, acquires grotesque proportions like the gargantuan hay bales (Fig. 1, 2). The fantastical designs of Makarov’s mind, like those of the Paper Architecture movement, materialize on various surfaces in Balian’s film.

The haunting landscape of the film’s conclusion, underscored simultaneously by unsettling merry-go-round music and Khrapachyov’s dark electronic synths, becomes a psychic space, an imaginary topos in which Makarov, like other disaffected late Soviet architects, takes refuge. Makarov literally plunges into a pile of hay and covers himself with straw in an act of self-exile. The final shot of Flights in Dreams and Reality reads as a metaphor for the Soviet architect’s complete withdrawal into the imagination, for his psychic alienation from the realities of daily life. Indeed, Makarov’s self-erasure charts his own maturational devolution. On his fortieth birthday, arm-wrestling and pulling pranks, he regresses from a middle-aged man to a teenager, whereupon, chasing boys on bicycles through a field, he degenerates into a boy. Then enveloping himself in wet straw, he becomes a newborn. This forty-year-old reenacts a return to the womb, a withdrawal to the security afforded by maternal gestation. It is no wonder that Balian begins Flights in Dreams and Reality with Makarov writing a letter to his estranged mother. Makarov’s hay bale is as much of a birthplace as it is a gravesite, a topographical marker of this Soviet architect’s non-existence.

The association between death and sleep that Balian’s film consistently draws cannot help but recall that famous passage from Don Quixote uttered by Sancho Panza, which is read aloud in Tarkovsky’s Solaris. “All I know is that so long as I am asleep, I have neither fear nor hope nor trouble or joy. God bless the man that invented sleep […] the universal coin with which everything is bought […] Sleep, I have heard say, has only one fault, it is like death.”10 The state of being asleep is comparable to death. The confusion and harshness of reality disappears when we lose the capacity to experience time: to sleep is to die. The somnambulant protagonist of Flights of Dreams and Reality thus forwards a very different, darker fantasy of escape than the happy-go-lucky escapist entertainment that cinema has long afforded its viewers, whether it be Disney cartoons or Stalinist musicals. Indeed, the very first film—the Louis Lumière’s Workers Leaving the Factory (1895)11—associates film with an idea of escape. The short actuality shows a multitude of laborers exiting a factory’s gates. Cinema itself begins as the workday ends, at the fulcrum point between labor and leisure. The new medium allies itself with the moment of escape from the measured time of the workplace. These newly liberated workers can now enter the spellbinding world of entertainment. Lumière is not filming “workers” so much as he is filmgoers, that is, a crowd headed to the movie theater. The line of escape in Flights in Dreams and Reality,however, does not point to recreation. That film figures an escape into sleep, nonexistence—a world without labor or leisure. The stagnated conditions that Balian is responding to Flights in Dreams and Reality is, in fact, reproduced in his languorous onscreen world, offering neither his characters nor viewers respite.

The part of a disillusioned, womanizing artist, who succumbs to a world that can no longer accommodate his talents in Flights in Dreams and Reality,prepared Iankovskii for his follow-up role in Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983), a similar “flight” hovering somewhere between fantasy and reality. Shot during the early days of Tarkovsky’s self-imposed exile from the Soviet Union in Italy, Nostalghia is the product of a displaced subjectivity, an unmoored imagination cycling through the same questions of psychic, geographic, and cultural dislocation fueling the creative energies of the Paper Architects. The film likewise registers its existential crisis architecturally.

Nostalghia erratically cycles between the Italian present of Tarkovsky’s protagonist, Andrei Gorchakov, and his daydreams and hallucinations of his Russian past. The former is typically shot in interior settings and in color, but in muted and sickly shades of brown, green, and grey, while the latter with lush black-and-white film stock in outdoor settings. Counterintuitively, Tarkovsky’s black-and-white palette, which he long maintained could more effectively convey the “truth” of any given scene than could flashy technicolor, is brighter than all the colors in Nostalghia put together. The alternations between these differently illuminated topographies are triggered unexpectedly by glances and shifts in atmosphere, thus capturing the fractured state of Gorchakov’s inner-world. Visual and audio motifs—dripping water, barking dogs, wind chimes—carry seamlessly over from Russia to Rome, and vice-versa. Tarkovsky unmoors his narrative from any fixed spatial coordinates; his viewers get lost in a thick web of spatial associations and details. Like Makarov, Gorchakov is shot sleeping for extended periods of time. Tarkovsky presents us with a kind of death-in-life, a character who, even in Rome, cannot shake his existential ennui.

Tellingly, the film’s other protagonist, Domenico, an Italian madman living on the outskirts of Rome and heralding the end of the world, dwells in a crumbling house overlaid in vines that is exposed to the elements. Noisy rainfall intermittently penetrates his abode, signaling Domenico’s liminal position in the contemporary world; he is neither inside nor outside, neither here nor there. “Society must become united again,” Domenico says later before lighting himself on fire. Death is a realm devoid of binaries. If Makarov’s “death” recalled the words of Sancho Panzo, Domenico’s does those of Jacques Lacan: “I think where I am not, therefore I am where I do not think.”12 Domenico enters a “society” that has never experienced the sort of disunion that he laments: the world of the dead. He, too, elects for a more extreme version of what it is to escape.

Domenico’s open-ended domicile, moreover, channels the incorporation of the organic in the designs of the Paper Architecture movement, which freely laced the natural elements into metal, stone, and plastic, the conventional substances used for making buildings. The elemental world exerted a restorative effect on the hyper-rationalist layout of modernist Soviet architecture, which organized greenery only insofar as it “maximized” livability and a neighborhood’s scenic qualities. Domenico’s house in Nostalghia, by contrast, exhibits a nature before its taming. It even houses inside of itself a model replica of the Italian countryside that blurs together with Tarkovsky’s landscape shots. This space within a space—also seen in Tarkovsky’s next film, The Sacrifice (Ofret, 1986)—rhymes with the disorienting, Möbius strip-like edifices of Paper Architecture.

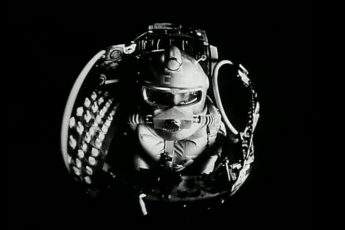

But it is Nostalghia’sfinal shot, an arresting imagescape of a Russian cottage, a dacha, ensconced in an Italian abbey, the Abbey of San Galgano in Tuscany, that presents the clearest example of Paper Architecture’s influence on late Soviet cinema, an architectural connection that has escaped the attention of scholars despite the film’s exhaustive critical attention.13 This (meta-)physically disjointed structure enacts a transcendental longing, a nostalgia, for a world without division, for a prelapsarian time before the Tower of Babel’s fall (thus foreshadowing the cultural and linguistic strife that would engulf Eastern Europe after the Soviet Union’s collapse several years later). This image remarkably resembles the heavenly but hazy towers committed to canvas by Yuri Avvakumov,14 Paper Architecture’s most prominent practitioner and theorist, who drew on the phantasmagorical work of the eighteenth-century Italian designer Giovanni Piranesi.

The haunting beauty of Tarkovsky’s tower resists the standardized conventions of the postwar built environment that put a primacy on efficiency and modesty (Fig. 3). Gorchakov’s (and Tarkovsky’s) longing for psychic creative freedom takes on material form here in Nostalghia in the shape of stone, grass, wood, and sky. Tarkovsky uses the elements as his building blocks to “construct” Gorchakov’s mind onscreen. The architectural impulse of Tarkovsky’s visual language is hinted at by the title of his book on film theory, a kind of cinematic manifesto, Zapechatlennoe vremia, or, in English, Sculpting in Time.

Yet Nostalghia’s architecturally impressive final image is but a visual trick, a blueprint cleverly making use of cinema’s ability (here via a slow zoom-out shot reminiscent of Kubrick) to disrupt our perceptual coordinates of time and space. As in the Paper Architects’ fantastical plans, Tarkovsky’s ensemble is unbuildable by design. It revels in its own whimsy before it dissolves into nothingness as Nostalghia cuts to black. Despite being made of stone, air, and earth, this Russo-Roman tower acknowledges its own ephemerality, its quality of make-believe. It monumentalizes that which is absent from the architectural regime of the modern world: eccentricity and fantasy. It is no wonder that Sartre once called Tarkovsky’s art an exercise in Socialist sur-Realism.15 Impracticality is the point. Mixed up with its longing for everlastingness, Tarkovsky’s tower, much like the flimsiness of paper, is highly fragile. It is the untouchable ether of one’s imagination, an escapist edifice straddling the divide separating the immaterial from the material. This image lays bare cinema’s ambivalent relationship to reality. It entices us with alternative time-spaces but cannot provide access. The fantasies teased by the cinema exist where we are not and are available, perhaps, only when we are not. The darkened, dreamlike state of a movie theater, in its own way, impels viewers to undergo the same process of self-dissolution experienced by Makarov and Gorchakov before a movie cuts-to-black, jolting us “awake,” back to when we are.

The phantasmagoric designs that Nostalghia shares with the Paper Architecture movement only intensified in the cinema of the late Soviet underground as Gorbachev’s reformist agenda (which framed itself architecturally, perestroika) pushed the Soviet Union to the brink of collapse. Ruinous, illusory topographies full of mayhem and drifters floating in between a kind of waking state and dreamscape define the canonical underground works of pre-fall Soviet cinema, such as Kira Muratova’s Asthenic Syndrome (Astenicheskii sindrom, 1988), Aleksei Gherman’s My Friend Ivan Lapshin (Moi drug Ivan Lapshin, 1984), and Aleksei Balabanov’s Happy Days (Schastlivye dni, 1991), which, in particular, cycles through the twilight streets of Leningrad, a city on the verge of implosion, through a focus on abandoned buildings, decaying imperial facades, paper and cardboard, a rogue hedgehog, and aimless—and nameless—psychiatric patients (Fig. 4, 5). This urban topography bleeds into a kind of impressionistic nightmare that puts a sinister twist on the whimsical designs of Paper Architecture. As Nancy Condee writes: “Balabanov’s city is the metal id, amoral, primal, compelled toward acquisition and gratification […] The nameless, transient hero of Happy Days shuttles between the prostitute’s house-cum-brothel and the cemetery.”16 Balabanov’s whole film is a kind of funhouse mirror of illusionary spaces that transports viewers to another (nether)world that acts as a potent metaphor of its uncertain times.

To conclude, then, the cinema of the late Soviet underground borrowed much of its aesthetic from an alternative, subterranean branch of Soviet design that flourished in a period of cultural and architectural stagnation, Paper Architecture. The blueprints of this movement communicated through the grammar of urban planning a longing for psychic escape, a kind of metaphysical transcendence, that the built environment of the late Soviet era, with its commitment to rationalization and its monochrome look, could not accommodate. These designs replaced the building materials of the above-ground with elemental, fanciful materials, such as diamond, sand, air, shadows, and wood, which built up a fantasy world unconcerned about its own materialization, a world as fragile as papier-mâché.

Similarly, several leading lights of late Soviet film, through the spatial tools of cinema, constructed onscreen equally fragile and fantastical structures that proceeded out of the Paper Architecture movement. These cinematic sites likewise yearned for an experience of psychic deterritorialization, perhaps best articulated by the landscape shot of a room full of sand dunes guarded over by a disappearing white bird in Tarkovsky’s Stalker. Yet these images, and architectural blueprints, were not one’s usual escapist fantasies. This imagery is all closely related to death and self-dissolution. These are not merely counter images to reality but ones advocating for reality’s negation. These dreams of eternity and oneness, momentarily consoling artists and characters, only compound one’s pre-existing disaffection, reminding viewers of the taboo aspiration that has preoccupied philosophers since antiquity: the human’s subterranean desire for death. As long we are subjected to time, and this subjection reveals itself most forcefully in the certainty that we must die, we cannot be at peace, and peace wants ever-lastingness, which only nonexistence can provide.

The longings for timelessness and wholeness promised by the spatial and cinematic texts of the late Soviet underground are only realizable where and when we are not: in sleep, in clouds, in movies, and, darkly, in death. The screen became a dynamic site of architectonics, a space of escape, on which new spatial imaginaries found a home, a home distinctly not of this life world.

References

- 1.Taras Sass, “Polety vo sne i naiavu,’’ 25-i-kadr: nezavisimyi zhurnal o kino (August 22, 2009): http://www.25-k.com/page-id-158.html [Accessed on April 1st 2021].

- 2.For a theoretical discussion of the idea of thereness and outside-ness (vnye) in late Soviet culture, see Alexei Yurchak, Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 205): 126-157.

- 3.Catherine Cooke, “`A Picnic by the Roadside or Work in Hand for the Future?’’’ AA Files no.18 (1989): 15-16.

- 4.Constantin Boym, “Notes from Underground,’’ ID, Magazine of International Design 36, no. 3: 28-41.

- 5.http://artoblaka.ru/blog/bumazhnaya-arhitektura-utopichnyie-fantazii-n/ [Accessed on April 20 2021].

- 6.Fabien Ballet, “À fleurets mouchetés: L’architecture soviétique sous le glacis brejnévien,’’ Cahiers du monde russe 54, no.1-2 (2016): 16.

- 7.Jamey Gambrell, “Brodsky & Utkin: Architects of the Imagination,’’ The Print Collector’s Newsletter 21, no.4 (Sept.-Oct. 1990): 125.

- 8.https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-11-11-ca-974-story.html [Accessed on April 20 2021].

- 9.Giuliana Bruno, Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film (London: Verso, 2002), 27.

- 10.M. de Cervantès, Don Quixote, trans. John Ormsby (New York: Norton, 1981), 801.

- 11.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DEQeIRLxaM4 [Accessed on April 20 2021].

- 12.Lacan, Écris: A Selection, trans. Alan Sheridan (Routledge: London: 2001), 166.

- 13.Stefan Schmidt W., “Somatography and Film: Nostalgia as Haunting Memory Shown in Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia,’’ Journal of Aesthetics and Phenomenology 3.1 (2016): 27-41; Christy L. Burns, “Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia: Refusing Modernity, Re-Envisioning Beauty,’’ Cinema Journal 50.2 (2011): 104-22.

- 14.https://snob.ru/entry/174903/ [Accessed on April 20 2021].

- 15.Jean Paul Sartre, “Discussion on the criticism of Ivan’s Childhood,’’ trans. Madan Gopal Singh, originally published 1962, nostalghia: http://www.nostalghia.com/TheTopics/Sartre.html [Accessed on April 1st 2021].

- 16.Nancy Condee, The Imperial Russian Trace: Recent Russian Cinema (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 222; 226.

Leave a Comment