Between the Fragment and the Ruin

Socialism in the Films of Kira Muratova

Vol. 98 (October 2019) by Masha Shpolberg

Early on in Kira Muratova’s Getting to Know the Big, Wide World (1979), the three central characters visit a potter’s studio. They watch in silence as a pot grows up out of the potter’s hands. On their way out, one of them steps up on the fender of a truck and proclaims: “For the modern man, a plane flying in the sky or a rocket tearing itself away from the Earth on the television screen is a common sight. But how many people in our time have seen how a potter works?”1

This scene sets up an antinomy between the industrial and the manmade, the modern and the traditional, which will become one of Getting to Know the Big, Wide World’s central structural devices. Misha visits the potter regularly, bringing him clay from the construction site at which all three characters work. “Try this clay, Father. I’ll bring you some more from the fourth quarry.”2 Hearing this, Liuba asks: “Is he your son?” and the potter answers, “it’s just a form of expression.” This scene is redolent with the nostalgia one finds more commonly and fully expressed in Tarkovsky’s films—nostalgia for a world where people exist in organic connection to one another and the natural environment. It is a world the Soviet Union actively sought to transform and set itself against. When Misha asks Liuba to marry him in the film’s concluding scene, he offers her a pot with the words: “Here, I made it myself. He says it’s crooked, no good.” There is a slight frisson of subversion as Liuba accepts the gift. Her simple phrase, “I like it,” affirms both her love for Misha and their shared Romantic, individualist ethos.3

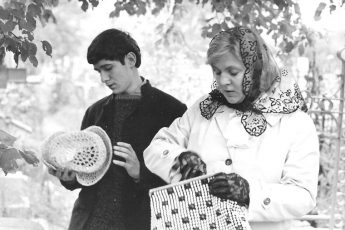

Getting to Know the Big, Wide World was Muratova’s third film. Her first two, Brief Encounters (1967) and The Long Farewell (1971) focused on women’s affective experience and were condemned by the Soviet authorities for their “unsocialist, bourgeois realism.”4 As a result, Muratova was unable to direct for eight years. It was only thanks to persistent lobbying on behalf of friends and admirers (including fellow filmmaker Aleksei German), that she was given an opportunity to shoot again, this time not at the Odessa Film Studio but at Lenfilm in St. Petersburg.5 The script, based on a short story by Grigori Baklanov, promised to be anodyne: a love story set against the background of a construction site that sees the characters grow up in tandem with the factory and city they are building. While the plot recalled the first socialist realist classic—Fyodor Gladkov’s Cement (1925)-, Muratova’s interpretation has more in common with the first satire of the genre, Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit (1930).6

The film is set in an unnamed location, somewhere in the provinces. Young people have come from all over the USSR, in Liuba’s words, “to build… a big city, a big factory.” Liuba reveals at one point that she is originally from a small town outside of Nizhny Novgorod, in Russia; Misha is from Zhitomyr, in Ukraine. Yet other characters are clearly marked by their speech and reveal themselves to be Belarussian. The construction site—like all Soviet construction sites—is to be a melting pot, a crucible of the new, Soviet people.

De juris, everything goes according to script: like Cement, the film includes a celebratory scene toward the end in which various officials congratulate the workers on the completion of the factory. Moreover, the very last scene shows the workers massed before a new apartment complex, about to move in. De facto, the view on the ground looks very different. The film opens with the car carrying Liuba and Kolia, her first companion, stuck in the mud. Their workplace appears to be in a permanent state of incompletion, none of the workers particularly preoccupied with its progress. Even in the film’s final moments, as Liuba and her friends make their way from the trailers in which they had been living to the finished apartment complex, they traverse a landscape of mud, steel frames, and exposed concrete blocks—fragments of unfinished buildings. As in The Foundation Pit, the socialist project appears stillborn, a literal and metaphorical quagmire. Echoing the Old Testament, the film ends with the wanderers poised to enter the Promised Land—but we never quite see them get there.

The built environment of Getting to Know the Big Wide World is all the more striking as it differs so strongly from Muratova’s two earlier films. The female protagonists of Brief Encounters and The Long Farewell are both shown living in pre-revolutionary buildings. Much of Brief Encounters, in particular, is set inside the heroine’s apartment, which is filled to the brim with antiques, historical wallpaper, and china. The core conflict the film explores is between the settled life of Valentina and the willful vagabondism of her beloved, a geologist named Maxim. Valentina’s “old” apartment is thus meant to reinforce the viewer’s understanding of her as someone deeply rooted.

There is one brief scene, however, already in this film, that speaks to Muratova’s growing fascination with the khrushchyovka as an emblem of late socialism. First erected en masse under Khrushchev (1953-1964), these apartment complexes were to provide a temporary solution to the Soviet Union’s dramatic housing shortage. Khrushchev famously predicted the “achievement” of communism in twenty years’ time—that is by the 1980s. The low-cost buildings erected under his reign were granted a twenty-five year life span, the idea being that within that time they would be replaced by more high-quality housing stock.

In Brief Encounters, Valentina (played by Muratova herself) is an official of the city’s housing authority. At one point, she visits a new residential construction whose builders, either through avarice or neglect, have failed to provide running water. Both the builders and the residents are clamoring for her to declare the building completed. The builders want it off their hands, and the residents are desperate to move in. Valentina, ever strong, refuses to do so until the problem has been fixed. There is a sense that Valentina’s character is intimately connected with that of her own apartment. Comfortable in that pre-revolutionary refuge, Valentina is not beholden to the same rules and stresses as the rest of Soviet society and seems to float above it.

Getting to Know the Big Wide World features no such safe havens. Its interiors are without exception makeshift and temporary: the construction site, the trailer Liuba shares with a number of other female workers, and the cabin of Misha’s truck. Again, the film hints at an isomorphism between the shoddy, standard-issue structures and the personalities that inhabit them. Liuba, Misha, Kolia, and their colleagues all strike the viewer as somehow blank. Liuba, in particular, experiments with wigs and make-up, invents stories and repeats clichéd, pre-fabricated phrases, as if an actress in search of a persona or—in film scholar Mikhail Iampolski’s recasting of Musil, “a [wo]man without qualities.”7

Her pronouncements about love and happiness (“they don’t make it in factories, even on the best conveyor belts”) sound hollow at first, but slowly gain meaning with every repetition. The speech of Kolia, Liuba’s first partner, is equally stitched together from common phrases. Misha distinguishes himself in this context by his relative silence and, when he does speak, by the unusually literal nature of his expressions. (When he says he is “missing a foot” he means it.) In this way, the film thematizes homo sovieticus’ search for authenticity and individuality in the face of material poverty and cultural uniformity.8

Muratova was not the only one to recognize the dramatic potential of juxtaposing idiosyncratic characters with the dullness of official language and, above all, official architecture. In the late 1970s, the khrushchyovka would have something of a cinematic moment, becoming a topos of interest to both popular and high-brow filmmakers. Eldar Riazanov’s hugely successful Soviet comedy The Irony of Fate, or Have a Nice Bath! (1976) was the first to capitalize on the buildings’ ubiquity and to explore their cinematic possibilities. An animated prologue illustrates the mass proliferation of this type of apartment block. The romantic comedy that then follows is predicated on the idea that even within this uniform world there may be room for play and chance: its protagonists meet as a result of a misunderstanding, because they live in identical apartments on identically named streets—albeit in two different cities.

Riazanov’s light, humorous vision would be countered by a darker one at the Soviet bloc’s Western extremity. In 1979, one year after Getting to Know the Big, Wide World, Czech filmmaker Věra Chytilová (whose biography and sensibility bear striking resemblances to Muratova’s) would produce Panelstory, a grotesque comedy about people occupying a similar, unfinished apartment complex. In the end, however, there would be nothing to laugh at in Hungarian director Béla Tarr’s The Prefab People (1982), a Cassavetes-style portrait of a young marriage on the brink of disintegration—set, once again, against the backdrop of a communist apartment complex.

Though all these films are committed to discreetly (or not so discreetly) undoing socialist realist tropes, Muratova’s Getting to Know the Big, Wide World stands apart due to its paradoxical combination of self-consciousness and sincerity. Muratova scholar Jane Taubman sees the film as a pivotal moment in the director’s career, away from the “the verisimilitude of the two black-and-white ‘melodramas’ to a new phase she herself described as ‘ornamentalism’ (dekorativnost’).”9 This shift was marked by a change in Muratova’s team, from cinematographer Gennadi Karyuk to Yuri Klimenko (who would later go on to work with Sergei Paradjanov). Klimenko’s mobile, searching camera creates a sense of surfeit movement that parallels other forms of excess in the film: the narrative excess of the love triangle at its center and the verbal excess of Liuba’s and Kolia’s speech.10

The ‘ornamental,’ even baroque style of the film—its camerawork, dialogues, and narrative structure—thus stands at odds with the brute, utilitarian nature of its setting. The factory and apartment complex in-the-making become stumbling stones rather than stages on the road to socialism. The incomplete, abandoned buildings that dominate the landscape become allegories of the socialist project: fragments of what it could have been, ruins of what it aspired to be, but never was.

Though the film’s initial distribution was severely limited, Russian critics have since picked up on its strange temporality, the sense that the action plays out in some kind of endgame, with everything already past, and nothing new in sight. Film critic Andrei Plakhov sees in the film a transition from “the modernism of the 1960s to that, which we now call postmodernism.”11 Zara Abdullayeva, in turn, described it as a “post-avant-garde film, as if someone had crossed Pasternak and Shukshin.”12

In the mind of any reader familiar with Eastern European Studies, Getting to Know the Big, Wide World also calls to mind the late Svetlana Boym’s writings on ruinophilia and nostalgia. “‘Ruin’ literally means ‘collapse,’” Boym wrote, “but actually, ruins are more about remainders and reminder. A tour of ‘ruin’ leads you into a labyrinth of ambivalent temporal adverbs—‘no longer’ and ‘not yet,’ ‘nevertheless’ and ‘albeit’—that play tricks with causality. Ruins makes us think of the past that could have been and the future that never took place, tantalizing us with utopian dreams of escaping the irreversibility of time.” Nearly a decade before the “Soviet experiment” was over, Muratova’s film dared to wrench it from its own promise of immortality. In her deft hands, the long-promised communist ‘forever’ turned into ‘for now,’ its ‘glorious tomorrows’ into a more or less abject series of ‘todays.’

References

-

1.Original Russian: “Для современного человека, летящий в небе самолёт или отрывающаяся от земли ракета на экранах телевизора, всё это привычное глазу зрелище. Но сколько людей в наше время видели как работает гончар?”

-

2.Original Russian: “Попробуйте эту глину отец. Я тебе ещё из четвёртого карьера привезу.” “Он что, ваш сын?” and “Это так, форма обращения.”

-

3.Original Russian: “Вот, сам сделал. Он говорит кривой, бракованный.” “Мне нравиться.”

-

4.S.D. Bezklubenko, minister of culture of the Ukraine after a screening of “The Long Farewell”, as quoted in Jane Taubman, The Cinema of Kira Muratova, The Russian Review 52:3 (July 1993), 373.

-

5.Jane Taubman, Kira Muratova: Kinofile Filmmakers’ Companion 4 (New York and London: I.B. Tauris, 2005), 27.

-

6.Although completed in 1930, Platonov’s novel would not be published in the Soviet Union until 1987. It was published abroad in English translation in 1973, however, and circulated widely for many years before that within the Soviet Union through the practice of “samizdat”: the copying and distribution of illegal literature through clandestine networks. Muratova would certainly have been familiar with, or at the very least aware of the work, given its cult underground status.

-

7.Mikhail Iampolski, “Muratova: tri filma o liubvi’ [“Muratova: Three Films About Love”], Kinovedcheskie zapiski 82 (2007), http://www.kinozapiski.ru/data/home/articles/attache/90_115_1.pdf.

-

8.Again, one can trace Muratova’s concern with idiomatic clichés, and her playful attempts to subvert them, back to Nadia’s initial monologue, “to wash or not to wash,” in “Brief Encounters”.

-

9.Taubman, op.cit., 27.

-

10.This structure parallels that of “Brief Encounters”: both involve a love triangle with a woman at its center. In “Brief Encounters”, it is a matter of two women interested in the same man; in “Getting to Know the Great, Wide World”—of a woman torn between two men. The ‘indecency’ of these plot lines served as an excuse for Party officials to severely limit the films’ distribution. It is important to note in this context that a contemporary film about a love triangle, “The Autumn Marathon” (1979) was widely distributed. One cannot help but wonder if that was because the love triangle there had a man at its center, unable to decide between two women.

-

11.Original Russian: “от модернизма 60-х годов к тому, что мы сейчас называем постмодернизмом”.

-

12.Original Russian: “«Познавая белый свет» — поставангардный фильм, как если б породнили Пастернака с Шукшиным, — прошел мимо, как косой дождь.”

Leave a Comment