Adorable Cog

The Ideological Fashioning of Femininity in Soviet-Era Cinema

Vol. 146 (Summer 2024) by Nora Furlong

In Grigori Aleksandrov’s 1936 Circus, there is a scene wherein the ferocity of a raised eyebrow leaves the audience stamping their feet in approval, persuaded of a triumph that is a bit more ideologically abyssal than meets the eye. An interior is barely lit by a sallow Moscow sky, and a door opened to the left doesn’t add much illumination to the room. A man enters, a jump cut occurs, the chandelier combusts, and an apartment worthy of Dominique Francon appears. But the woman who follows the first besuited and sleek-almost-slimy figure moves like no Francon; Marion Dixon, Circus’ heroine – an American woman in need of a good dose of Soviet ideology – advances as if led to the gallows, her shoulders slightly forward, her gaze upon the floor. We’ve seen this before; a walloped woman walks to her domestic death, her husband sheds his snakeskin as he hangs up his coat. And then we are walloped; we are privy to Dixon’s face in the next shot, a mid-frame divided between Dixon, who faces us, and Franz von Kneishitz, her keeper, as he sidles up to her right shoulder. She is completely composed; something around her eyes and mouth, an obdurate nerve, girds our loins for her resolve as an undistressed damsel, a resolve that nears execution as von Kneishitz nears what he thought was his prey. There is a cut to his line of vision, which Dixon turns to meet, and as she raises her eyes, it’s decided; Dixon glares and glowers with such savagery that the crackle of Circus’ old footage seems intentional, a way to display the daggers generated by her look. The next three shot reverse shots exhibit the effect of Dixon’s intensity on von Kneishitz; his eyes widen in alarm, her eyes narrow in cheek-sucking spite, his form sinks off screen as he lowers himself to his knees, and their roles – established by the manner with which they entered and the preconceptions regarding gender – are reversed.

The wide shot that follows shows Dixon turning to face us while von Kneishitz grovels against her gown, accessing his former aggression only when she rips her skirt from him; he lunges at the table and asks her what she wants. “To stay in Moscow,” is hissed with the same vehemence that twisted her stare. At this, von Kneishitz becomes hysterical; he wrenches open a suitcase, then a closet, pulling clothes off their hangers and tossing them at Dixon. A striking series takes place here; in between shots of furs, bejeweled garments, and other luxuries dragged and jerked from their inertia, Dixon is displayed in the middle of the living room, standing stoic and ignorant of von Kneishitz’s commodified bitching. In the first of two shots, she faces the left of the screen, draped only in her original gown. The latter visual, following another mink made animate as it is whipped out of sight, shows Dixon now facing right, almost enveloped in the silk and lace which von Kneishitz has thrown at her. She is an entirely detached statue, a transformation fortified by the about-face of her position. A viewer might feel uneasy here, concerned whether Dixon’s ferocity has been drowned in velvet, whether the fineries of von Kneishitz’s violence have overwhelmed her resolve. Be at ease, audience; the next mid shot of Dixon’s face demonstrates her continued defiance, and the lace kerchief haloing half of her head only affirms the air of Dixon’s “renunciatory virtue.”1 Von Kneishitz, repeating a part-admonition-part-plea over all the clothes he has purchased and flung at her, is met with Dixon’s steely declaration of her material and spiritual transformation: “The Mary you bought these [clothes] for is no more.”

Marion Dixon, played by the “prima donna of the Soviet Screen,” Lyubov Orlova, is a circus performer forced to flee her native United States for birthing a mixed-race child. She stumbles into a train car in the first few minutes of the film, is recognized and arrogated by Franz von Kneishitz, and travels to Moscow to eke out a living, miserable beneath the weight of her past and this German jerk. Finding work in a Russian circus, Dixon slowly sheds the shame of her banishment, falls in love with Ivan Petrovich Martynov, the incarnation of the “perfect Stalinist character,”2 and begins to align her femininity with the New Soviet Woman, an idea first proffered by the Bolshevik party.3 The scene described above is the genesis of her transformation; although slightly kitschy in its representation of metamorphosis by way of conquering clothes and some crass chap, the episode succeeds in instilling a sense of joyful and resilient evolution. We feel spurred into action, and if the action is only to applaud Dixon’s rebirth as a figure not in need of drapery – provided either by lavish fabric or a possessive partner – so be it, hurrah! This reaction, however, this shout of approval, requires examination; the silk shan’t be pulled over our eyes by a film so bolstered by ideology that it is “propaganda-poster worthy.”4

Most Stalin-era Soviet films acted as victorious vehicles of persuasion, presenting the country-then-the-world Stalin hoped to build as a utopia populated by laughing laborers. They generally succeeded; take, for example the frenzied fraternity one feels after watching Battleship Potemkin, or the provincial pride induced by Trubyshkin’s triumph in Volga-Volga. The ubiquitous equality of Soviet society is Circus’ métier, and is orchestrated in material and abstract terms; Dixon is presented as a wretched woman from the West, who, through an assumption of Soviet ideals, accesses a truer, purer version of herself. This purity is contingent on the adoption and performance of ideology; the film goes to glittering lengths to prove the superiority of Soviet customs – regarding one’s appearance, comportment, and interpersonal relationships – over inadequate Western mores, demonstrating that in the Soviet Union it matters not whether one is white, black, female, male, stupid, or smart.

This seductive promise, the acceptance of any and all into the Soviet Union, is reflected in the atmosphere of the circus; the freewheeling freakshow seems the ideal landscape in which to demonstrate revolutionary terms of embrace. It appears almost as a Bakhtinian carnival; past identities are abandoned, new roles are assumed, and love between the unlikely blooms in the twinkling, topsy-turvy panorama of the Soviet circus. It is not altogether nuts, not altogether an endorsement of social deviance and rejection of norms; every aberration functions for the purpose of High Stalinism, demonstrating how this structure, in defiance of the past and the West, will be a utopia for all. Thus, Dixon and her bastard son are welcomed with open arms into the Great Family, and her assumption of mother/lover within the new environment is not exactly a carnivalesque antithetical; it is, rather, a rebirth.

Circus is principally a pageant of ideology, and as is typical in pageantry, the costumes count; Dixon’s renaissance is aided by and explicitly exhibited in the restyling of her wardrobe throughout the film. At first, when performing in Busby Berkeley-esque productions or backstage pantomimes of flirting and learning Russian, Dixon materializes as the buxom, glitzy heroine one would expect. When she accepts love (Communism) into her heart, the emphasis on her femininity is reduced through a stripping of sequins, through a simplification of her outfits. Dixon begins to engage with her acts in a sportswoman-like manner, with body-smoothing leotards and an attitude of performing for the people. Her identity as a woman is still essential in regard to her romantic relationships, but the priority is placed on Dixon’s capacity as a worker, as a member of the masses. Dixon wears her many hats well; she is a mother, a wife, and a patriotic performer for Russia, an exemplary “femina sovietica.”5

The concept of the New Soviet Woman was defined in concert with the expectation of all Soviet citizens; in order to create and serve the promised Elysium, each citizen must abandon this “each,” and prioritize that which they can offer in a communal capacity. Women were encouraged to refuse their conventional placement in the domestic sphere, although not to the extent that they “jeopardise their roles as mothers and child-bearers.”6 They were instead prompted to include their potential as workers in addendum to this role. The New Soviet Woman was she who does it all; the birthing and rearing of children, the housekeeping and cooking, as well as a ten-hour shift at the factory. In order to accomplish this, the previously important elements of femininity – the upkeep of one’s appearance so as to attract a husband – kind of, sort of, fell by the wayside. The value assigned to women’s physicality began to alter; it became a case of competence rather than attractiveness.

This is all well and good, until one recalls the bridge between ideology and reality; socialist realist films generally depicted “one-dimensional archetypes […] who [embody] the socialist ethos of struggle for the common good,”7 and ended up ignoring the nuances of what was actually expected of women. Dixon is a perfect example of the well and good; her trajectory in the Soviet environment is completely “morally affirming and nationally redemptive,”8 and she ends up fulfilling all positions envisioned for the New Soviet Woman perfectly. Her motherhood is affirmed, since Soviets are able to accept a black child without qualms, she attracts and is attracted by Martynov, and she finds joy in her labor, in serving the community, realizing true “happ[iness] in the USSR.” Beneath the radiant lights of the big top, Dixon seems shiny and new, cleansed of capitalism, and reborn as a sanctified Soviet.

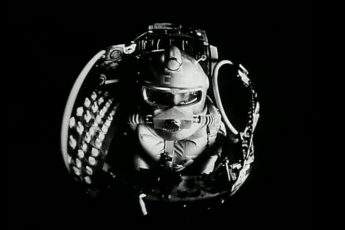

Defeminization by way of communist ideology is especially conspicuous in the scenes where we see Dixon prepping herself for and carrying out a stunt. We anticipate, in accordance with other cinematic renditions of the female performer, the squeezing of hips and breasts into a scintillating little number. We expect the film, like any proper musical, to spotlight the talent as well as the body of the protagonist. But Dixon’s take on stardom is far more focused on professionalism. The film emphasizes her ability to serve through entertainment; before a dangerous tap dance atop a cannon, we are privy to Dixon’s preparation, and see her steeling herself to face the crowd rather than priming and primping. Her costume avoids an unnecessary exposure of skin, negating the typical supposition of how a woman should be presented, and indicates Dixon’s liberation from sexualizing capitalism; the attention instead is on Dixon’s “highly regimented perfor[mance], stylized marionettish movements, and cheery, professional manner.”9 Circus’ socio-cinematic aim is explicitly realized in Dixon’s stunt scenes, as they carefully neutralize the visual and material lure of a woman performing.

The enactment of ideology on femininity is better illustrated in conjunction with another cinematic representation of such. The 1939 film Ninotchka, which some consider to be MGM’s response to Circus, had as its star the enigmatic Greta Garbo, the “Swedish Sphinx” of Hollywood’s Silent Era. The movie is a talkie, though, directed by Ernst Lubitsch, and was incentivized by a pitch for a comedy about a “Russian girl saturated with Bolshevist ideals [who] goes to fearful, Capitalistic, monopolistic Paris. She meets romance and has an uproarious good time. Capitalism not so bad after all.”10 Nice. It is a film in keeping with its period, with the “bright and eyebrow lifting dialogue” popularized by screenwriters and directors such as Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett. What makes Ninotchka an anomaly is its parody of the extant political landscape; the film references Stalin’s Great Purge and his five-year plans, using them as fodder, a terrific risk in light of how many Soviet citizens were “disappeared” for jokes and anecdotes. A moment in the film that exemplifies Hollywood’s nerve-wracking gumption; Nina Ivanovna Yakushova arrives in Paris, and after a grim handshake with each of her three comrades, she tells them that things back home are “very good. The last mass trials were a great success. There are going to be fewer but better Russians.” Good moment to gulp. As expected, it was banned in the Soviet Union upon release, seeing to fruition the first line from The New York Times’ review of the film, which simply said “Stalin won’t like it.”11

Putting Ninotchka’s intrepid approach to still recent atrocities aside for a moment, a relevant element of the film – its depiction of the feminine identity as demarcated by a socio-economic ideology – begs a comparison to Circus. Both films fall within the capitalist v. Communist romance genre popularized before and during the Cold War,12 and each attempt to demonstrate the liberative nature of their respective credos through disparate expressions of femininity. Each paints the other as an environment of despotic evil, a nation and national idea that represses not only political freedom, but the freedom of true expression. Both protagonists are displaced women; Marion is an American fleeing to Moscow from the big old bigot that is Western society, and Nina is a Russian sent to Paris to oversee the sale of jewels seized during the Russian Revolution of 1917. Amidst an unfamiliar environment, the women are at once adapting to the culture-specific mores of the landscape and still in possession of their past selves, setting up an inevitable expectation and enactment of transformation. The cardinal narrative of each film is the metamorphosis of the heroine; her new surroundings stand in stark contrast to her old identity, forcing a shedding of the characteristics that do not fit, after which she emerges, newer, better, purer. This last adjective is significant; the women who appear from their cocoons are presented as themselves in their most natural, intrinsic form, as if the transformation was a purification.

Fashion is utilized in Ninotchka just as in Circus to convey the heroine’s development from oppressed to liberated, although the former proposes an acceptance, rather than a rejection, of material goods. The feminine act of consumption is used to distinguish between the repressive Soviet structure and the pretty liberty of the West; while Circus offers freedom in the neutralization of gender, Ninotchka advocates for a manifest performance of femininity – or at least the finery/flirtation associated with it – as true emancipation. Early on in the film, Yakushova passes a shop window displaying a rather whimsical hat. She pauses to remark upon the ridiculousness of a civilization which “permits their women to put things like that on their heads.” It is an objectively foolish little fedora, but Yakushova’s snubbing is more so meant to indicate her ascendancy over consumerist creed; the statement distances and distinguishes Yakushova as a woman not like the others, a superior Soviet, not a mall rat. Later on, after cupid shoots his fatal arrow, we see Yakushova pulling this same inessential from a bottom drawer, pulling it over her severe hairdo, and perhaps not admiring, but taking in the effect in front of a mirror. She still looks rather forlorn and uninterested when faced with her reflection, but it is a significant stage in her evolution; Yakushova is acquiescing to the feminine-associated urge to assign importance to her image, taking steps to improve or accessorize.

The next scene is between her beau, the Count Léon d’Algout, and his butler, engaging in a perfunctory, meta-conversation about the equality of labor and wages. The doorbell rings, and d’Algout rushes to welcome in a behatted Yakushova, looking embarrassed but enamored. She has apparently realized the attraction of material goods, especially when they induce such attractive compliments from a man, compliments which she receives with only a slight attempt at self-effacement: “I don’t look too foolish?”

Yakushova – severe and seemingly staunch in her severity – is poised for the foible of her Communist character upon arriving in Paris; in conjunction with the allure of accessories, the seduction narrative in Ninotchka furthers the idea of freedom through conventional femininity. Yakushova may interact with the city of love and luxury with a turned-up nose, but due to a fateful encounter while waiting between taxi whistles with d’Algout, it becomes more and more difficult to buttress herself against the amorous nature to which all seem inclined. They begin a game of cat and mouse, the latter more stone cold than small and skittish, and an exchange of dialog in d’Algout’s apartment offers a telling representation of the Communist feminine identity: d’Algout, in fits, asks Yakushova “what kind of girl [she is] anyway?” Her response would make Stalin proud: “Just what you see. A tiny cog in the great wheel of evolution.” His response would make Bacall smitten: “You’re the most adorable cog I’ve ever seen.” Despite the glib quality, this banter is important; Yakushova understands herself, her role and purpose, in accordance with Soviet ideology, and seems to allocate any human potential to the service of the state. If she was to blush at d’Algout, then reproduction, not romance, would be deemed an appropriate course of action. Thus, Ninotchka’s romantic narrative is used to further delineate the Soviet Union as a dour, repressive place. The depiction of love between a Soviet woman and a Western man gives the audience a way to culturally understand and differentiate between capitalism and Communism,13 the latter condemned as inherently inhuman.

But this is reductive; the Soviet Union, despite the chasm between ideology and reality, did try to put in place legal measures to recognize the equality of all citizens; in theory, and at first, it was the most progressive place on earth.14 The basic tenets of communist ideology emphasize that, among other harmful hierarchies, the oppressive relationship between women and men must be eradicated for liberation to be truly attained; the removal of legal restrictions and the establishment of certain socio-economic rights not only aimed at placing men and women on equal footing (if such equality was only aimed at and never reached), but detached them from the potentially regressive professional/domestic spheres through equal expectations of labor. Gaining value through work rather than gendered conduct was an orientation that sought to negate obstructive body politics and emphasize the communal worth of the individual and the importance of becoming a part of a whole. To be “a tiny cog” was a point of pride, as it linked one to a greater system of social development, and offered a kind of relief in regard to the inherent human anxieties over one’s merit, anxieties which were framed as romantic hindrances to national progress.

By reacting to Yakushova’s recitation of communist dogma with such a word as “adorable,” d’Algout quickly and succinctly disregards her learned ideology, preferring a more sentimental interaction with the world. The adjective, since it is related to appearance, also aids in the feminization of Yakushova, as it allocates value to that which was previously insignificant: her looks and desirability as attested by the male sex. Because d’Algout finds Yakushova attractive, her role as one among many is invalidated; when her face is differentiated by the estimation of a man, she emerges from the masses, seemingly free. Yet the simplicity of this liberation should be questioned as much as Circus’; the reductive binary of “USA/good and USSR/bad” diminishes the fact that Yakushova unfetters herself only to classify her femininity by another set of physical and behavioral expectations. Instead of a cog, she is now a coquette, and will be treated as such. Any tenderness between this Soviet woman and Western man is lost as they are transfigured into a trope. Ninotchka applies an individual narrative of romance to an international sphere to achieve a serviceable contrast between ideologies; instead of lending nuance to Yakushova’s potential sexual liberation, her response to d’Algout’s seduction is staged as a victory of Western ideals over Soviet inhibition.

Romance in Circus also serves to promote a national and ideological belief system; love and attraction are as simplified as Dixon’s appearance, and function as the confirmation of her rebirth. The trajectory from Dixon’s sexualized self to a purer expression of identity is most manifest in the simplification of her garments, but her relationship with Martynov is also a refashioning of bygone corruption into safe bliss; Dixon assumes a somewhat sterile style of femininity, nullifying her promiscuous past as she is surrounded by a new, familial type of love. Because partnership is still necessary, Dixon finds a mate, but the love she develops for Martynov is a more sentimental expression of female desire, and the safe coupledom she enters into with him seems wholeheartedly warranted. Abandoning von Kneishitz and his tangible statements of affection, Dixon rejects the capitalist control of feminine sexuality and undresses her exploitation. Her transformation is cinched when declaring her love for Martynov; Dixon writes him a letter in the elementary Russian he’s taught her thus far, crossing out her signature of “Marion” and replacing it with “Masha”. And thus, the revolutionary romanticism of and within Russia transforms Dixon into her true self – a Soviet.

The scene which ends Circus, the final and most triumphant of the film, shows a mass in march, all in white, with Dixon and Martynov at the front. As angelic as they appear, both characters seem glossed over, disappeared in a homogenous bleached blob. The march follows an intensely tender demonstration of Soviet acceptance; von Kneishitz, fascist villain extraordinaire, decides to reveal Dixon’s secret and stomps around the circus sawdust with her kid, a crying Jimmy, in his arms. He throws a tantrum about gasp – a black child! – while Dixon flees, until an audience member asks, in admirable Russian fashion, “nu chto?”15 A group of Red Army soldiers wrestles von Kneishitz out of the ring and Jimmy is whisked into the embrace of the friendly Soviet people. The kumbaya is unnecessary to get into, but the culmination is remarkably sweet; Jimmy is cradled in various babyshkas’ bosoms as they sing a lullaby composed of lyrics in Russian, Ukrainian, Yiddish, Uzbek, and Georgian. It is an internationally, but particularly Soviet, manifestation of integration.

An exhibition of a May Day parade is next; Aleksandrov intercuts the fictional orchestration of Dixon and Martynov leading a mass of circus performers and other Soviet citizens with actual footage of the 1935 event. The shots of the couple among the cohort are divided by Lenin- and Stalin-adorned flags, crowds moving in sync, and close-ups of understanding as it dawns on Dixon’s face, all while the “Song of the Motherland” is belted out in the background. If one can get past the overtly propagandistic euphoria, Dixon’s complete coalescence into the herd is striking. In line with the power of unity in communist ideology, Dixon’s femininity is rearranged to fit in with the New Soviet Woman; her gender is neutralized, her body is liberated, and her purpose is clear. The identical costumes are the most demonstrative aspect of this rearrangement; when one squints, the white tunics are all that remains conspicuous. Picking out Dixon from this herd is to pick out merely another “unisexed woman.” The typically erotic nature assigned to femininity is “sublimated into love of country,”16 and Dixon is flattened and fit into a one-among-many role.

The rebirth of Dixon into an integrated, Sovietized citizen is contingent on her affirmation of socialist ideology, an ideology that promoted a sublimation of the material and more overtly sexual aspects of femininity. Her defeminization is staged more broadly in the circus – an environment of performance and camouflage through costuming – and more specifically in the transformation of her appearance. One of the most pivotal scenes in Circus shows a weeping Dixon, just walloped by von Kneischitz, pulling her disguise, a black wig, halfway off to reveal her natural blonde hair. She gazes at a photo of a strong, stable, also blonde Martynov, who suddenly enters, asking about a suitcase – sweet Martynov is a character “somewhat perplexed by the machinations of the plot”17 – and she smiles at him, her familiar, her love, her comrade. Dixon is blonde from then on, having far more fun, and she is liberated from the oppression of her capitalist past as a New Soviet Woman.

Yakushova ends up similarly content, although as a result of a completely disparate enactment of ideology. Her clinical attitude and “stifled sexuality” is offered as a result of political repression, and Ninotchka demonstrates that “only when [Yakushova] sheds her Communist role can she fulfil herself.”18 The shedding of this role generally occurs overtly, but it mimics Circus in its specifics; the characters’ clothing and appearance are the most altered by ideology, as if their metamorphosis depends on a material acquisition or rejection of fashion and feminine conduct. Both films maneuver femininity with an emphasis on appearance and convention; while Circus makes use of preconceived gender roles in order to define them as Western and ultimately defy them, Ninotchka condemns the unnatural nature of Communism, promising that “in the tussle between Marx and marriage, marriage always wins out.”19

Issues arise in any comparison of Communist and capitalist mores, especially in their artistic renditions; it is necessary to avoid solutions that are as quick as a jump cut, as serendipitous as falling in love in Paris, and as persuasive as a parade. The function of ideology in cinema is ever important, and its analysis reveals the latent phenomena at work when a screen is lit up, deciphering why an audience laughs and if they sing along at the end. There is more to explore apropos Circus and Ninotchka; the films are significant individually, in conversation with each other, and when contextualized in an international cultural archive. Instead of beginning this essay with a question, I’d like to end it with inquiries; was the ideologically motivated defeminization of women in the Soviet Union an aspiration or a practice, more so aligned with legal fact or dogmatic fiction? Does a presentation of one’s femininity rely on the beliefs of the system to which one belongs? As a woman, is one more content when abdicated of gender, or endowed with the accessories and taught the behavior befitting an expectation of the feminine? And, finally, where can I get a hat like Ninotchka’s?

- Holmgren, Beth. ““The Blue Angel” and Blackface: Redeeming Entertainment in Aleksandrov’s “Circus”.” The Russian Review, 66(1), 2007; 4. ↩︎

- Salys, Rimgaila. The Musical Comedy Films of Grigorii Aleksandrov: Laughing Matters. Intellect Books, 2009; 147. ↩︎

- Kollontai, Aleksandra. Woman and Family in the Communist State. Komunistka, No. 2, 1920, The Worker, 1920, Selected Writings of Alexandra Kollontai, Allison & Busby, 1977; 17. ↩︎

- Holmgren, Beth. ““The Blue Angel” and Blackface: Redeeming Entertainment in Aleksandrov’s “Circus”.” The Russian Review, 66(1), 2007; 12. ↩︎

- Nikolaevich, Sergei. “Poslednii seans, ili Sud’ba beloi zhenshchiny v SSSR”, Ogonek, 1992; 22. ↩︎

- Schuster, Alice. “Women’s Role in the Soviet Union: Ideology and Reality.” The Russian Review 30(3), 1971; 263. ↩︎

- Taylor, Richard. “The Illusion of Happiness and the Happiness of Illusion: Grigorii Aleksandrov’s ‘The Circus’.” The Slavonic and East European Review 74(4), 1996; 607. ↩︎

- Ibid.; 611. ↩︎

- Holmgren, Beth. ““The Blue Angel” and Blackface: Redeeming Entertainment in Aleksandrov’s “Circus”.” The Russian Review, 66(1), 2007; 18. ↩︎

- Eggert, Brian. ““Ninotchka”.” Deep Focus Review, Deep Focus Review, Oct. 1939; 3. ↩︎

- Nugent, Frank S. “THE SCREEN IN REVIEW; ‘Ninotchka,’ an Impious Soviet Satire Directed by Lubitsch, Opens at the Music Hall–New Films Are Shown at Capitol and Palace.” The New York Times, November, 1939. ↩︎

- Heller, Dana. “A Passion for Extremes: Hollywood’s Cold War Romance with Russia,” Comparative American History 3(1), March 2005; 89. ↩︎

- Laville, Helen. “‘Our Country Endangered by Underwear’: Fashion, Femininity, and the Seduction Narrative in ‘Ninotchka’ and ‘Silk Stockings.'” Diplomatic History, vol. 30(4), 2006; 631. ↩︎

- “The Revolution of 1917 […] promised to provide women with economic employment on an equal basis with men. The first Soviet Constitution of 1918 proclaimed in Article 22 the equality of all citizens in the Soviet Republic – regardless of sex, race, nationality – and established in Article 64 the right of women to elect or be elected to the Soviets on an equal footing with men. These changes were spelled out again in Article 122 of the Constitution of 1936, which accorded women equal rights and an equal footing with men in all spheres of political, economic, social, and cultural activity.” Schuster, Alice. “Women’s Role in the Soviet Union: Ideology and Reality.” The Russian Review 30(3), 1971; 263. ↩︎

- Along the lines of “so what?” ↩︎

- Schuster, Alice. “Women’s Role in the Soviet Union: Ideology and Reality.” The Russian Review 30(3), 1971; 268. ↩︎

- Taylor, Richard. “The Illusion of Happiness and the Happiness of Illusion: Grigorii Aleksandrov’s ‘The Circus’.” The Slavonic and East European Review 74(4), 1996; 605. ↩︎

- Salys, Rimgaila. The Musical Comedy Films of Grigorii Aleksandrov: Laughing Matters. Intellect Books, 2009; 147. ↩︎

- Strada, Michael J. and Troper, Harold R. “Friend or Foe? Russians in American film and foreign policy, 1933-1991” Lanham, MD and London, The Scarecrow Press, 1997; 254. ↩︎

Leave a Comment