The Politics of Recognition: Jews in Czech and Polish Post-Communist Cinema

Vol. 28 (April 2013) by Ewa Mazierska

Ewa Mazierska (University of Central Lancashire) discusses the representations of Jews in Polish and Czech films in postwar cinema, focusing on the last twenty years, against the background of the political and cinematic histories of the respective countries. She reflects on the construction of characters and narratives in the films at hand, seeking to tease out whether they offer us a vision of the Jew as culturally different from the society in which he operates. The article’s principal conceptual framework is the ‘politics of recognition’, as discussed by Charles Taylor.

The (In)visibility of Jews on Screen

Representation of Jews in Polish and Czechoslovak (and successive Czech and Slovak) cinemas after the Second World War was affected by many factors. Firstly, the fact that the majority of Jews living in these two, and later three countries, were assimilated into the indigenous populations makes it difficult to establish whether a specific person is Jewish. And yet, without agreeing whom we regard as a Jew, it will be difficult to discuss how Jews are represented in cinema. Hence, for the purpose of simplicity I will consider characters to be ‘Jewish’ when they are identified as such in the film either through dialogue or overt visual/cultural characteristics. Secondly, Poland and Czechoslovakia had different war histories. Although in both countries Jews were persecuted during the war, it was Poland rather than Czechoslovakia where the ‘Final Solution’ took place. Auschwitz, a physical place that became a symbol of the genocide of Jews, was located in Poland. The third factor is the anti-Semitic practices of the political authorities of the respective countries and the actions of ordinary people. One such example were the Stalinist purges and show trials in Czechoslovakia in the early 1950s, when the Secretary General of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, Rudolf Slánský, as well as fourteen other leading Communists, of whom eleven were Jews, were arrested and accused of treason. Another was the Soviet withdrawal of diplomatic relations with Israel after the Six Day War in 1967, which was used to launch an anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic campaign in Poland. It led to the expulsion from that country of thousands of individuals of Jewish ancestry, including professionals, Party officials, and functionaries of the secret police. There are also many shameful moments in Czech-, Slovak-, and Polish-Jewish history, such as the massacre of around 300 Jews by their Polish neighbors in Jedwabne village in 1941, and of around 40 in Kielce in 1946. Events such as these result in a trauma on both sides of the crime, which, as many authors maintain, leads to repression, denial and silence – behavior which nevertheless can and should be deciphered as re-presenting the original event. Both the ‘spontaneous’ acts of anti-Semitism and those encouraged from the top affected the representation of Jews in the respective cinemas, including whether any ‘direct’ representation of Jews was allowed to be produced and to circulate. Iwona Kurz argues that the Kielce pogrom and the events of 1967-8 affected the distribution and official reactions to two Polish films featuring the Jewish subject – Border Street (1948) by Aleksander Ford and The Long Night (1967) by Janusz Nasfeter. The latter film was shelved and only had its premiere in 1992.1 We can also conjecture that the conviction that making films about Jews is particularly risky put some directors off from tackling the subject.

Accordingly, in order to draw any conclusions about the representation of Jews in Polish, Czech, and Slovak cinema, we should also consider films that only allude to Jews, in which Jews are invisible, yet present, or are given smaller roles than one might have expected. One such example is arguably the best Polish film about the camps, Andrzej Munk’s Passenger (1963). Munk’s film does not present any Jewish characters in active roles – we only see masses of Jews led to the gas chambers and learn about the rescued Jewish or Roma child. The film’s protagonist, Marta, and her fiancé, are both Polish, although being Polish does not matter much in the film, because they are positioned as anti-Nazi. I must admit that for a long time I did not give much thought to the fact that the Jews are practically excluded from Munk’s narrative. Only when I started to research this film did it dawn on me that this is a ‘Jewish film without Jews’, so to speak. I was not alone in having this impression. Someone asked me about the Jewish absence when I was presenting this film some years ago at the Imperial War Museum. Some of the viewers who engaged in discussion after the film ascribed a Jewish identity to the film’s protagonist, Marta. The question of the absent Jew in Passenger gains particular poignancy in the light of Andrzej Munk being rather secretive of his own Jewish background and his position as a leading Polish director, rather than a Polish Jewish director. One wonders whether Munk’s decision to emphasize Polish martyrdom and heroism in Passenger was a consequence of his genuinely Polish identity or rather a sign of the suppression of his ‘true’ Jewish identity. A similar question can be posed in relation to another of Munk’s films, Bad Luck (1960). The main character, Piszczyk, is a Pole, but is taken for a Jew due to having a typically Semitic physique. He continuously suffers from bad luck and a lack of a genuine identity – he is like a chameleon trying to adjust to constantly changing circumstances, once becoming a socialist, another time an anti-Semitic nationalist. Bad Luck is one of the most popular films in Polish history, with ‘Piszczyk’ being a byword for an ordinary, non-heroic Pole. But he can be regarded as the epitome of a Polish Jew who has to conceal his Jewishness, even playing an anti-Semite in order to survive.

Another example of films without Jews, but possibly about Jews, are Roman Polanski’s early films, such as Two Men and a Wardrobe (1958) and Mammals (1962). The cruel and spiritually impoverished world their characters inhabit bring to mind l’univers concentrationnaire, where human life is reduced to ‘bare life’. Again, such an interpretation is encouraged by our knowledge that Polanski came from a Jewish family and his mother perished in the gas chambers. In this context it is also worth placing The Dark House (2009) by Wojciech Smarzowski, which, as I argued elsewhere, entreats itself to be considered in the context of the recent discussions about the Jedwabne massacre.2 The Dark House is set in the Polish province during the period of martial law (introduced in 1981) and shows how seemingly friendly and decent people (friends and members of the same family) start to be violent towards one another. Although all characters in the film are Polish, the director refers to various types of otherness that pertain to Jewishness; a connection encouraged by the mise-en-scène whose elements, such as pitchforks and burning barns, were used to describe the pogrom in Jedwabne. Of course, the absence of Jews in Passenger has a different meaning than in the context of The Dark House; in the first case we can talk about an ‘accented absence’; in the second, about a metaphorical presence.

All these examples testify to the influence of the extra-diegetic context on the way a film at hand is interpreted, such as the director’s background, as we tend to look for ‘absent Jews’ in films made by Jewish rather than non-Jewish directors. We also inscribe Jewish motifs more easily into films made in countries ‘intimately’ linked to the Holocaust, such as Germany, Israel, or Poland, rather than those literally and metaphorically distant from the death camps. Authors who experienced over-average exposure to the Holocaust, a category which includes a large number of Jewish researchers, for example Omer Bartov,3 as well as myself (although I am not aware of having Jewish ancestors), tend to write Jewish motifs into the films, or express surprise about their absence more readily than those who have seen fewer films of this kind.

A similar set of problems were encountered by authors examining the representation of Jews in German cinema. Thomas Elsaesser, in an article meaningfully entitled ‘Absence as Presence, Presence as Parapraxis: On Some Problems of Representing “Jews” in the New German Cinema’, discusses some of Alexander Kluge’s films, especially Abschied von gestern – (Anita G.)/Yesterday’s Girl (1966) in the context of the Holocaust, although the films he considers were set in the present.4 Justin Vicari examines possible traces of anti-Semitism in Fassbinder’s films states: “Fassbinder depicts the Holocaust as a kind of negative presence, a shadow on the present, the return of the repressed through moments in which violently disturbing unconscious material breaks through the deceptively calm surface of consciousness”.5 Vicari claims that those metaphorical renderings of the Holocaust, which he finds, for example, in Fassbinder’s Katzelmacher (1969), affect him more strongly than the Holocaust films ‘proper’. This is also the case for me. Yet, to move on to a safer territory, from now on I will focus on the films with more ‘visible’ Jews.

I would like to discuss them in the light of what Charles Taylor describes as the ‘politics of recognition’. He puts forward the following claim:

A number of strands in contemporary politics turn on the need, sometimes the demand, for recognition. The need, it can be argued, is one of the driving forces behind nationalist movements in politics. And the demand comes to the fore in a number of ways in today’s politics, on behalf of minority of ‘subaltern’ groups, in some forms of feminism, and in what is today called the politics of ‘multiculturalism’… The thesis is that our identity is partly shaped by its recognition or its absence, often by the misrecognition of others, and so a person or group of people can suffer real damage, real distortion, if the people or society around them mirror back to them a confining or demeaning or contemptible picture of themselves. Nonrecognition or misrecognition can inflict harm, can be a form of oppression, imprisoning someone in a false, distorted, and reduced mode of being.6

Taylor proceeds by arguing that such politics are based on two assumptions: first, on the equal dignity of all individuals and social groups and, secondly, on their distinctness and, hence, the right to preserve their language and other cultural particularities. He also points to a possible tension between these two aspects of ‘recognition’. A person’s right to dignity might be granted, but not his/her special rights as a member of a given group. This tension is thrown into relief in a situation when a minority group, such as that of Jews living in a diaspora, is pulled in two directions: on the one hand, assimilation with the majority population and culture, on the other, asserting its specific identity. This might also lead to the conflict between various minority and oppressed groups, for example, women and ethnic minorities, each demanding a special treatment as a way of compensating them for previous injustices, thereby giving rise to a ‘politics of difference’.7 The choice depends on internal and external factors, and most importantly, on the perceived advantages of following one of these routes.

I would like to find out whether specific films reflect the domination of one or the other way of recognizing Jews – as members of a larger group (for example Polish or Czech citizens or Europeans, or even humans) or as members of the distinct group of Jews. Of course, the Nazis in their dealings with Jews rejected their right of recognition, either as human beings, citizens of a specific country, or as Jews. Their attitude towards Jews was based on what Taylor describes as misrecognition – labeling a person ‘Jewish’ meant depriving him or her a right to dignity and, indeed, basic humanity.

Jewish Characters in Polish and Czechoslovak Cinema after the Second World War, till the End of Communism

Despite the fact that the relationship between Jews and the non-Jewish population was not an easy subject in the respective countries, Jewish motifs persist in Polish and Czechoslovak postwar cinemas. There was practically no decade without some films presenting Jewish characters, and the vast majority of them are concerned with the Holocaust. The remaining films usually represented pre-Holocaust periods, such as Jealousy and Medicine (1973), directed by Janusz Majewski, and The Hourglass Sanatorium (1973), directed by Wojciech Jerzy Has. By contrast, there were hardly any films showing Jews living in postwar Poland or Czechoslovakia. This can be regarded as a testimony to the decimation of the Jewish population during the Second World War and the filmmakers’ unwillingness to engage in a debate about the position of Jews in the respective countries post-WWII.

Peter Hames attributes the persistence of Jewish motifs in Czechoslovak cinema to the strong Jewish representation within the Czechoslovak intelligentsia, which includes writers such as Jiří Weil, Arnošt Lustig, Norbert Frýd, and Ladislav Fuks, and directors such as Alfred Radok, Jan Kadár, and Miloš Forman. Furthermore, there was a strong Jewish element within the postwar leadership of the Communist Party itself.8 In Czechoslovakia the vast majority of films representing Jews were made by Jewish directors that often cast Jewish actors, based on books written by Jewish authors. This might also be a reason that they typically put the plight of the Jewish character at the center of the discourse, apply his/her point of view, or balance the perspective of Jewish and non-Jewish characters. Examples are The Long Journey (1950), directed by Alfréd Radok, Romeo, Juliet and Darkness (1960), directed by Jiří Weiss, Transport from Paradise (1962), directed by Zbyněk Brynych, Diamonds of the Night (1964), directed by Jan Němec, The Shop on the High Street (1965), directed by Ján Kadár and Elmar Klos, and Juraj Herz’s The Cremator (1968).

The international recognition of some of these films, including an Oscar which was awarded to The Shop on the High Street, acted as an incentive for Czechoslovak directors to continue exploring this subject. In the aforementioned films, we observe a balance of male and female characters, but Jewish women are more memorable than their male counterparts. I refer especially to Hana in Romeo, Juliet and Darkness, Mrs. Lautmannová in The Shop on the High Street, and Kopfrkingl’s daughter in The Cremator. The focus on women results from the conviction that the harm inflicted on women, especially those who were very young or old, as is the case in the films at hand, was especially vicious, rendering the Nazi policy of ethnic cleansing as cruel in the extreme and, at the same time, universalizing the suffering of Jews. Mrs. Lautmannová suffers not as a Jewish woman, but rather as an old woman; it is her deafness and fragility which makes the film’s Slovak protagonist identify with her plight, provoking his willingness to help her. Equally, she does not see in him a representative of a different ethnic or cultural group, but somebody belonging to her family.

Poland also had its fair share of directors of Jewish origin. Of the five or six most acclaimed Polish postwar directors, three are of Jewish ancestry: Aleksander Ford, Andrzej Munk, and Roman Polanski, as well as the leading female Polish director, Agnieszka Holland. Yet, unlike Radok or Weiss in Czechoslovakia, they have not been perceived in Poland as directors of ‘Jewish-centered films’, perhaps with the exception of Holland, especially since her recent film In Darkness (2011). Ford is remembered predominantly as the director of The Teutonic Knights (1960), which is the greatest box office success in Polish history, Munk as the author of Bad Luck, a film about ‘Polish fate’, and Polanski as the father of the Polish New Wave thanks to his debut Knife in the Water (1962). With the exception of Aleksander Ford, who made Border Street, Munk, Holland, and Polanski preferred not to make films with Jews in the main roles during their respective periods of working in Poland. Such a choice can be seen as a sign of their assimilation into Polish culture, or else as their reaction to Polish anti-Semitism; anxiety that tackling Polish-Jewish affairs might jeopardize their careers. During the period in question Jews were recognized as members of a Polish nation rather than a minority group of Jews. The second hypothesis is supported by the fact that after leaving Poland, Ford, Polanski, and Holland all made films about Jews. The minority presence of Jewish filmmakers was exacerbated by Munk’s death in a car crash in 1961 during the shooting of Passenger.

Consequently, in Poland the vast majority of films concerning Jews and the Holocaust were made by Polish directors, most notably by Andrzej Wajda, the ‘ultimate’ Polish film auteur, who directed Samson (1961), Landscape after the Battle (1970), The Promised Land (1975), Korczak (1990), and, after the fall of communism, Holy Week (1995). Predictably, they offered a Polish perspective on Jews. The central characters in them are Poles, and they confirm Iwona Irwin-Zarecka’s claim that “for the majority of Poles, it is their own victimization during the Nazi occupation that represented a formative trauma”.9 Jewish characters typically serve only as a litmus test to check Polish martyrdom or, more rarely, anti-Semitism, cowardice, greed and malice. In Wajda’s films, a class affects the distribution of these features, with positive attitudes towards Jews being attributed to the Polish intelligentsia, and anti-Semitism to the working class.10

In Polish cinema, as in its Czechoslovak counterpart, Jewish women are more prominent than Jewish men. Examples include Nina in Landscape after the Battle, Lucy Zucker in The Promised Land, and Irena in Holy Week. The prevalence and distinctiveness of female Jewish characters is reflected in the fact that the only two articles known to me that discuss the representation of Jews in Polish cinema from a gender perspective, written by Elżbieta Ostrowska’s and Joanna Preizner, are about Jewish women.11 Both authors argue that Jewish women are so visible in Polish films because they provide a clear contrast to idealized Polish women who are used as a metaphor for Polishness. Thus, unlike Polish females, who are blond, meek, desexualized, and reconciled with their fate, Jewish women in these films are dark, hysterical, over-sexualized, demanding, and ungrateful for the help they receive. They often prefer to die than live in hiding. Preizner goes as far as suggesting that the Jewish women in Polish films are often represented as dangerous, even witch-like.12 Juxtaposing a Polish woman with a Jewish woman thus enables edifying the former, thus condoning Polish reluctance to offer help to the latter.

The majority of male Jews presented in Czechoslovak and Polish films conform to the type I described elsewhere, borrowing from Isaac Deutscher “as non-Jewish Jews”: Jews assimilated into the host society,13 respectively Czech, Slovak, or Polish. Such are Jewish men in Radok’s The Long Journey, Samson, Korczak, Wajda’s The Promised Land, and in Postcard from a Journey (1984) by Waldemar Dziki. Additionally, some Jewish men in Polish films come across as weak, emasculated, or homosexual. Unlike Jewish women, they tend to accept their fate. The most extreme example is Jakub Rosenberg in Postcard from a Journey, who prepares himself for the journey to the death camp, rather than engaging in resistance, which will be the standard attitude of Poles faced with extermination by the Nazis, as represented in films about the Second World War. Such a representation also conforms to the stereotype of a diaspora Jew as passive and weak; a stereotype which was strongly opposed in Zionist discourses dominating Israeli culture in the first decades of its existence.14

The second group, which is much more prominent in Polish cinema, is comprised of religious Jews, demanding recognition as non-Poles. We find them in Austeria (1983), directed by Jerzy Kawalerowicz, Majewski’s Jealousy and Medicine, and Tadeusz Konwicki’s Jump (1965). They usually remain impenetrable to Poles. They are looked at from the outside and exoticized. We get the impression that they cannot be helped because tragedy is inscribed in their fate, perhaps they even yearn for it.

Jews in Polish Post-Communist Films

To demonstrate how Jews are represented in Polish postcommunist films, I chose three films, The Pianist (2002) by Roman Polanski, Weiser (2001) by Wojciech Marczewski, and In Darkness (2011) by Agnieszka Holland. This is a small sample out of tens of films devoted to the topic, especially in the context of the Second World War, made in Poland after the fall of communism. This in itself can be seen as an indication for the (for many, belated) recognition of Jews in Polish culture. There is no ambiguity about their identity; they are depicted as Jews, which might be seen as a sign that Jews are nowadays recognized as members of a minority group rather than of a larger group, such as Polish victims of the Nazi extermination policies. However, in the films I chose for my discussion, the question of how Jews should be recognized is posed within the narrative, and each film suggests a different answer to it. Due to space constraints, I will focus on the films’ narratives and construction of the main characters, leaving aside their visual style.

All three films refer to the Holocaust, but the first and third can both be described as ‘literal’ Holocaust narratives, while the second offers its metaphorical rendition. The first was made by an ‘insider’, Roman Polanski, a Jewish artist who shared similar experiences to that of his main character, whose viewpoint the film adopts. While I cannot comment on the family history or identity of the director of the second film, Wojciech Marczewski, there is no doubt that he is ‘recognized’ as a non-Jewish Pole and artist, and I will argue that his film is made from a distinctly Polish perspective. Finally, the third one is made by Agnieszka Holland, a director of Jewish origin and, as I previously mentioned, one with specific interests in Jewish history and identity. However, Holland plays down her Jewishness and positions herself as a ‘transnational subject’. I will suggest that such an identity is reflected in the way she depicts her characters. Notably, all three films are not entirely Polish, but international productions with funding also coming from Germany, Denmark, and Switzerland.

The Pianist’s protagonist is Władysław Szpilman, composer and pianist, who is also a Holocaust survivor. During the war, Szpilman, together with his parents and siblings, was taken to the Warsaw ghetto. Unlike the rest of his family, he didn’t perish in Auschwitz, but stayed in Warsaw and managed to survive there during the war. After the war, he became one of the most successful authors of popular songs in Poland. Szpilman, as much in real life as in Polanski’s film, fits very well the stereotype of an assimilated Jew who sacrifices his distinctiveness for the benefits of the first type of recognition, as identified by Taylor. Indeed he can be regarded as an apogee of the type of a ‘non-Jewish Jew’ in Polish culture. Michael Oren confirms such a description, labeling Polanski’s Szpilman as a stereotypical European Jew: ‘cosmopolitan, artistic, godless, rootless, utterly unprepared for history, and averse to power’.15 Oren also notes that those same adjectives also describe a certain European ideal.

The immediate sign of such identity is the title of the film – The Pianist, which refers to Szpilman’s profession rather than other aspects of his identity, including his ethnicity or religion. Indeed, Władysław devotes himself to music with such ardour that he barely notices the bombs falling on Warsaw. Even when moved to the ghetto, his hands remain his main preoccupation. He makes sure they are in good condition, which would allow him to resume his career of a concert pianist when the war is over; a preoccupation emphasized by frequent close-ups of his hands. Moreover, Szpilman remains remarkably distanced from the reality of war. He sympathises with ordinary Jews suffering from hunger, but does not consider himself as one of them. Not in the least thanks to his talent, he belongs to the privileged strata of the ghetto population, playing in a restaurant visited by the richest Jews. But, equally, he distances himself from these war profiteers, represented according to anti-Semitic stereotypes, looking with disgust as they listen to the sound produced by golden coins. Szpilman does not join the resistance either, unlike his brother, instead regarding plotting against the Nazis as hopeless utopianism. Polanski shows that history proved Szpilman right – both war profiteers and the freedom fighters perished, while Szpilman saved his life.

In the film, Szpilman survives the war essentially because he is helped by people who do not see a Jew, but only a pianist in him. First he is plucked out by a Jewish policeman from the crowd of people who prepare themselves for what would be their journey to the death camp. The policeman places him in a special unit which remains in Warsaw. There he has a number of jobs, such as working on a construction site and in a storeroom. After that he is helped by his Polish friend Dorota. Finally, he is saved by the German officer, Wilm Hosenfeld, who upon hearing Szpilman playing Chopin not only spares the pianist’s life, but also brings him food and his own coat which allows him to survive the severe Polish winter. Szpilman is closest to death when the Soviet troops liberate Warsaw and see him in a German uniform. It is only when he begs, ‘Don’t shoot, I am a Pole’, that they spare his life.

Szpilman’s survival is facilitated, on the one hand, by the fact that he is a non-Jewish Jew and, on the other, by the good will and generosity of representatives of two nations which are implicated in the destruction of European Jewry: a Polish woman and a German man. Szpilman turns out to be even luckier than the main German character in the film, as he survives the war and resumes a successful career, while Wilm Hosenfeld is taken to a P.O.W. camp and perishes there. By conflating Jewish identity with European identity, and focusing on the sacrifice of ‘good’ Poles and Germans to help Jews, Polanski opts for recognition based on equal dignity of all individuals and social groups, rather than on the distinctiveness of some of them. He also works towards absolving Europe of guilt resulting from its role in the ‘Final Solution’. It can be suggested that through such representations of his Jewish protagonist and those around him, the director expressed his gratitude to Europe for saving him many times, including from a barbaric America, and conversely, Europe expressed gratitude to him for such a flattering portrayal by rewarding him with many awards, including the Palme d’Or in Cannes.

Despite Szpilman’s perceived closeness to Poles, he does not come ‘too close’ by engaging in sex with Polish women. Dorota, in whom he appears to be sexually interested, marries another man, and when Władysław meets her during the war, she is pregnant, removing any danger of her Jewish friend courting her. This lack of erotic connection between the characters can be seen as a means of accentuating Dorota’s noble intentions by portraying her as somebody following her heart rather than her flesh. At the same time, it can be regarded as a reflection of Polanski’s acceptance of the view that such relationships are improper: Poles and Jews should not mix. Thus, it is Szpilman’s Polish (as well as class) identity which bestows him with privileges, but he cannot enjoy all the privileges Poles take for granted because ultimately he is not quite a Pole.

While Polanski placed a Polonised Jew at the centre of his film, whose story allows him to provide a rather flattering portrayal of Poles, or at least of the Polish intelligentsia, Marczewski in Weiser chooses a Pole as his main protagonist. This man, Paweł, investigates a Jew that perished many years previously, not in the Holocaust, but in an event that bears important similarities to it. The narrative unfolds when Paweł, a sound engineer, returns to Wrocław in his native Poland after eleven years spent in Hamburg. Ostensibly he returns to live in a newly liberated, postcommunist Poland, but in reality he is prompted by a desire to find out what happened one momentous day in the 1960s, when he was thirteen years old. On that day, he was playing with a group of four friends near a disused railway tunnel. Among them was a young Jew, David Weiser, who previously proposed to blow up the tunnel. The children were meant to wait outside with the explosive device, but Weiser and the only girl in the gang, Elka, entered the tunnel anyway. Weiser was never found, dead or alive; and Elka was subsequently discovered near the tunnel, unconscious and lacking any memory of what happened. The school headmaster, the local priest, and the local representative of the secret services all tried to force the children to admit that they killed Weiser, but failed. In order to establish the facts, the adult Paweł approaches the three remaining witnesses of Weiser’s vanishing to find out who the real Weiser was.

I find the very narrative device used in the film meaningful, as it is predicated on the idea that Jews are different from Poles, either due to their identity or because of how they are recognized by Poles. To learn about his Jewish friends and neighbors, a Pole has to undertake an investigation, embark on a real and metaphorical journey to different places and times which might contain signs of his presence. To a Pole, knowing a Jew does not come easily. Why is that so? The answer suggested is that this is because the traces of their presence were purposefully erased – from the physical world, and from memory. Paweł learns that the house where Weiser once lived does not exist anymore, and his name is not included in the housing register office. One can conjecture that this comprehensive erasure of Jews from Polish cultural space reflects the view that there is, or at least was, no place for unassimilated Jews in Polish society. The only way for a Jew to be recognized was to be recognized as a Pole. Paweł’s journey is meant to test this hypothesis.

We see Weiser for the first time when he is harassed by a group of Polish children. The assault takes place after the last lesson of Catechism before the summer holiday. The fact that Weiser does not attend religious education is perceived by Polish children as a sufficient reason to bully him. Symbolically, this can be viewed as an indictment of the Catholic Church in the history of Polish anti-Semitism, as argued by Jan Gross.16 Weiser is rescued by Elka, who forces the children to leave the boy alone. This incident is observed by Paweł, who neither takes part in the harassment, nor defends the boy. This passivity, in turn, can be regarded as emblematic of the position taken by the majority of Poles in response to the killing of Jews by Germans and fellow Poles, a position discussed in a famous essay by Jan Błoński, “The Poor Poles Look at the Ghetto”, published in 1987 in the Catholic weekly Tygodnik Powszechny.17 This essay pointed at the different situations of Poles and Jews during the Second World War, with Jews being the principal victims of the Nazis, thus demanding recognition as a separate, minority group.

After Elka rescues Weiser, Paweł and his two classmates befriend him, most likely regarding it as an acceptable price for being close to the charismatic and pretty girl. Yet, Elka remains the only person in the neighborhood who is emotionally close to Weiser. To her, Weiser is not inferior to the Polish boys, but superior, as demonstrated by her observing his levitating with awe. She also participates in his dangerous experiments, lying next to Weiser on the airport runway, at the very place where a plane is about to land. Weiser is not the only Polish film from the postcommunist era in which Jews are represented as possessing supernatural powers. This motif is also prominent in films by Jan Jakub Kolski, the descendant of a Jewish Holocaust survivor, who in his films also takes issue with Polish-Jewish relations during and beyond the Second World War.18

In Kolski’s films, for example Miraculous Place (1994), and in Weiser, the miracles that occur in the presence of the Jewish characters, and which contribute to the films’ surrealistic style, are a measure of an almost impossible task the Jews had to undertake to survive in adverse circumstances. In Weiser, magic is the only way to make the situation of Weiser and the Polish children equitable. At the same time, his magical qualities are a marker of the boy’s otherness and of the Jews’ difference from the Polish mainstream, and by the same token, of a need to recognize them as a separate group. David himself does not strive to be assimilated into Polish culture; he wants to be accepted on his own terms. He succeeds, at least partially, as Elka and her friends accept him, but his eventual disappearance, most likely caused by suicide, suggests that he saw no place for himself in postwar Poland. We can also draw such a conclusion from Weiser’s talk with his grandfather or religious mentor, as recollected or imagined by Paweł. It transpires that he is an orphan, and being a twelve or thirteen-year old boy, he cannot be a child of the Holocaust victims. Their conversation suggests that Weiser’s parents died because they were not fit to survive in adverse circumstances. Weiser’s mentor does not want David to repeat his parents’ mistakes and the boy promises to follow his request. In light of this conversation, Weiser’s probable death in the blown-up tunnel can be interpreted as a kind of repetition of his parents’ death, but also that Weiser learnt from their mistakes and avoided their fate by masterminding his own death, rather than allowing others to kill him. The second interpretation is supported by scenes of Weiser constantly working on his physical and mental powers. He learns to endure pain, levitate and, ultimately, disappear.

Unlike Szpilman in Polanski’s film, which encapsulates reconciliation between Jews and Poles thanks to the assimilation of Jews into Polish and European culture, for which Szpilman is rewarded in the narrative, Weiser is a symbol of an unassimilated Jew, who carries within himself the pain of many generations of Jews oppressed by Poles and Europeans at large, and whom even the well-meaning Poles, such as Elka, cannot save from the weight of the history of accumulated prejudices.

When Elka meets Paweł in the contemporary part of the film, she confesses that she was in love with both Weiser and Paweł. Ultimately, however, she did not choose either of them. We can regard Elka’s naming her daughter ‘Rachela’ as a sign of her continuing sentimental attachment to Weiser because in Poland this name is regarded as typically Jewish, and rarely given to Polish children. Thus Elka, like Dorota in The Pianist, stands for the part of Polish culture which was open to Jewish influences. Yet, the fact that her passion for Weiser was never consummated points to the barrier between Poles and Jews which neither side is able to cross, of Jews ultimately being seen as different and as a consequence, feeling different.

The time Paweł returns to Poland is loaded with symbolism – 1989, the end of communism in his country and Eastern Europe at large. No doubt, for many people, and especially Polish Jews, this date brought hope of unearthing many painful incidents from the past. This hope was largely fulfilled, as signified by bringing into the public domain information of such events as the previously mentioned massacre in Jedwabne, postwar acts of ethnic hatred, and the plethora of artistic texts concerning the Holocaust.19 Inevitably, the process of unearthing these events pointed to the different fate and culture of (ethnic) Poles and Jews and, consequently, the need to recognize Jews as a separate group.

Although Weiser lends itself to a discussion of the context of the relationship between Polish, Jewish, and German histories and their identities, this aspect of the film was remarkably absent in its reviews. For example, the renowned Polish critic and film historian Tadeusz Lubelski regarded Weiser solely as a meditation on people of different generations, not on representatives of different ethnicities living in Poland. Furthermore, he argued that in contrast to the literary source of the film, a novel by Paweł Huelle, which encourages a political reading, Marczewski’s Weiser is a ‘personal’ film, which purposefully sheds the political baggage of its original, to indulge in nostalgia.20 The lack of references to the Jewish motifs of Weiser, observed in this and other reviews, testifies to Polish mainstream culture subsuming the past of Polish Jews for many decades , making Jewish experiences practically indistinguishable from Polish ones. Although Marczewski’s Weiser (as well as the previously mentioned films by Jan Jakub Kolski) testify to changes in the way the Jewish past is represented in Polish cinema, film criticism in Poland appears to lag behind these changes.21

Agnieszka Holland, who made In Darkness almost a decade after The Pianist and Weiser, and the publication of Jan Gross’s books which rendered Poles no less guilty of anti-Semitism than the Germans,22 inevitably was aware of the different ways Jews were portrayed in these films. Equally, she understood the dilemma: whether to present Jews in the Holocaust narrative as a minority group deserving a special attention, or as a part of a larger group suffering from Nazi/totalitarian oppression, which might include also Poles and some Germans.

The narrative of In Darkness has much in common with The Pianist, as well as other films about rescuing Jews, most importantly Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993). It concerns Leopold (Poldek) Socha, a sewer inspector and small-time crook who decides to help a group of Jews, following the liquidation of the ghetto by hiding them in Lviv’s sewers. Socha does it for the money, but in the course of the action he experiences a moral transformation, marked by his decision to continue helping the Jews even when they run out of money and take care of a baby born in their hiding place. Similarly, his wife is reluctant at first, but later accepts her ‘saintly’ role out of moral conviction.

There is no doubt that the Jews as presented by Holland are the main victims of the Nazi oppression. For this reason they deserve recognition and special treatment. At the same time, the director plays up the victimhood of Poles. Its special character consists in having to choose all the time between saving themselves and others. On one occasion the result is truly tragic, as when many Poles are hanged as a punishment for Poldek and his Jewish companion’s killing of a German soldier. We learn that Poldek did not enjoy the liberation from the Nazi regime for long, as he was killed by a Soviet military truck – ultimately he was thus a victim of totalitarian oppression in a way similar to the ‘good German’ in Polanski’s story. As Ostrowska argues, the film does not privilege either the Polish or Jewish perspective. The director mobilizes various cinematic devices, such as camerawork and the structuring of space, to accord Poles and Jews similar importance within the narrative.23 More importantly, from my perspective, Holland complicates the question of Jewish and Polish identity and, by the same token, the question of their recognition as separate cultural communities. The most important means of that is the use of language, typically regarded as a privileged marker of identity and hence a special right for recognition. As Ostrowska argues:

Capitalizing on the multivalent linguistic politics of pre-war Poland, Holland uses different languages to destabilize and re-define the relationship between Poles and Jews. The linguistic diversity represented by the Jewish group is also of special importance here. As they speak Polish, Yiddish, Hebrew, and German, they epitomize different models of Jewish diaspora that stretch out between two poles: assimilation and isolation. Thus, it is the choice of which language to speak that determines one’s Jewish identity. In one scene Chiger is attacked by his fellows for his knowledge of German as being a symbolic act of annihilation of his Jewishness. He retorts that for him this is the language of Heine, not only of Nazi perpetrators. Thus, his act of speaking German during the Holocaust serve as a symbolic act of reclaiming this language from the Nazi discourse. Moreover, different registers of Polish language, as used by both Polish and Jewish characters, as well as the problem of assimilation, in which language plays an important role, trigger off the constant tension between sameness and difference as permeating the Polish-Jewish relationship. (Ostrowska 2013)24

If In Darkness demands recognition for Jews as a special category, it equally demands recognition of various sub- and cross-cultural communities, such as German, Hebrew, Yiddish, and Polish speaking Jews, as well as minority groups within Polish community, such as Poles from Lviv. By extension it shows that the politics of recognition based on recognizing ethnic and cultural difference is both arbitrary (as one has to decide which differences are more important than others) and, therefore, impossible to implement in a just way, as ultimately each person is culturally different from another person, as Taylor observed. To recognize a specific group by granting it privileges is to deny privileges to another group. From this perspective the only rational and morally acceptable position is a politics based on recognizing the equal dignity of each individual and, by the same token, removing privileges from any group. Or at least this should be an ultimate goal, which, however, might be achieved only by temporarily granting privileges to previously misrecognized groups, such as Jews.

Jews in Postcommunist Czech Films

As comparators to The Pianist, Weiser and In Darkness, I chose three Czech films: Divided We Fall (2000), directed by Jan Hřebejk, Spring of Life (2000), directed by Milan Cieslar and Martha and I (1991), directed by Jiří Weiss. I describe them as ‘Czech’, due to their textual characteristics rather than the source of their funding. Martha and I is a German-French co-production and the director had lived in the USA for 20 years when the film was shot.

As with the films discussed previously, I divide them into films made by non-Jewish and Jewish directors. In the first category are Divided We Fall and Spring of Life; in the second Martha and I. Predictably, the films in the first category apply a perspective of non-Jewish characters and privilege their predicament. In this sense, they serve as Czech counterparts to Weiser. Martha and I, by contrast, employs a Jewish perspective, placing Jewish characters in the center of the narrative; hence, it can be compared to Polanski’s The Pianist. However, all three films are close to The Pianist because they render the Jewish characters as assimilated, cosmopolitan, refined and well-educated – as ‘non-Jewish Jews’, as defined by Isaac Deutscher, or as model diaspora Jews that do not need and should not be recognized as a minority group, to return to Taylor’s categories. They are also affluent, or rather they were affluent before they lost everything in the war. Leo in Spring of Life is the son of an ex-chief doctor of a sanatorium, which was subsequently changed into the ‘incubation center’ for the superior race. David in Divided We Fall is the son of a rich industrialist. Ernst in Martha and I is an affluent gynaecologist. Their class background adds to their identity and external perception as ‘non-Jewish Jews’. This is also strengthened by the fact that in the lives of all of them, Slavs and Germans play positive roles.

Yet, unlike Polanski’s film, where there is a clear division of roles, with Jews being cast as victims, and Poles and a good German as rescuers, in Czech films these roles are blurred. In Divided We Fall, the Jewish character, David, is first rescued by a Czech couple, Josef and Marie Čížek, but later he is required to help them by impregnating Marie. He is also helped by (Sudeten) German Prohaska, who knows about his hiding, but does not turn him in to the authorities. In exchange, after the war he saves Prohaska by admitting that the German man helped him. The twists of the narrative – which put one character after another in precarious situations and force the members of different ethnic groups to exchange favors – strip the Jewish character of his exclusive suffering and, consequently, his right to recognition as a Jew and a privileged victim of the Holocaust.

This idea is conveyed most effectively in the symbolic final scene of Divided We Fall. In a dreamy vision, Josef shows his newborn son (born on the day of liberation and virtually a product of collaboration, brought to this world by the mutual efforts of Josef, Prohaska and David) to a group of Germans and Jewish ghosts sitting together at a table. Petra Hanáková argues:

The final reconciliation – both of the living and the dead – is achieved through the valorization of the stereotype as a mask, a strategy, or a façade that only hides the generally good nature of the ‘normal people’. Ethnicity or even politics in this configuration virtually loses all importance, and although the film valorizes the (typically negative) stereotypes, they are replaced by another schematism that allows for the absolution of any guilt and also for the eradication of historical memory itself. Symbolically, the film thus ends with a vision of the continuation of the Czech nation as a product of the ethnic mixing of Germans, Czechs and Jews.25

We shall also add that this mixed Czech nation is rendered as Christian, or at least informed by Christian values, as suggested by the names Josef and Marie, given to the parents of the boy, who is, again, a product of the collaboration of representatives of different ethnic groups. Such representation, while acknowledging that Jews have a role to play in Czech society and culture, denies them autonomy, recognizing them (in the sense proposed by Taylor) only as members of a larger group: Czechs, Europeans or human beings. Such an idea is strengthened by the fact that David is depicted as entirely passive, almost devoid of subjectivity. He does not rebel against his fate of being locked up, and when given the task of impregnating Marie, he does not attempt to seduce her, but only does what is expected of him. This renders him different from Josef and Prohaska, who are full of energy, loud, and who do whatever they do their own way. One gets the impression that David and, by extension, Jews, have to be assimilated into a larger community to gain any identity, to find ‘a voice’. But, as Taylor points out, such lack of ‘voice’ might be a consequence of a previous misrecognition, resulting from colonialism or patriarchal oppression.

Spring of Life centers on Gretka, a young Slovak girl who is chosen to give birth to an Aryan child due to having been impregnated by a German man, this being a part of a Nazi experiment in eugenics coded ‘Lebensborn’, the purpose of which was to breed perfect children, able to carry on the Nazi project well into the future. ‘Lebensborn’ is an extreme example of what Michel Foucault and Giorgio Agamben term biopolitics – politics whose objective is deciding which life is worth living and which should be eliminated.26 Nazi biopolitics, as I already indicated, was an opposite of the modern idea of recognition, by being extremely hierarchical, pronouncing that those at the bottom of their hierarchy are not worth living.

However, due to a series of coincidences, Gretka isn’t impregnated by a Nazi soldier, but a young Jewish man called Leo, who works in a special camp where the experiment in creating an Arian Übermensch is carried out. The result, as in Divided We Fall, would be a hybrid – a Jewish-Slovak child, signifying an impure character of Slovak, Czechoslovak, or maybe European culture, in need of being recognized as members of a larger community.

Leo is shown as having more agency than Hřebejk offers to David. For example, he attempts to sabotage German plans by trying to cause the death of Gretka when she arrives at the camp, by directing her to the wrong path through a frozen lake. Nevertheless, it is Gretka rather than Leo who is the active party in their romance – Gretka visits Leo in his home to have sex with him, and brings him medicine when he falls ill. Her relationship with Leo, especially when he is ill and bed-ridden, is more similar to that of a parent and a child. She can even be compared to Mary, tending to Jesus; an impression strengthened by stylizing the image of Gretka and Leo on Pieta, which is also an image of two Jewish people who are, however, recognized predominantly as ‘universal people’, devoid of any national or cultural particularities.

Both David and Leo are very young, on the verge on adulthood. This fits the narratives, which focus on the plight of the Slavic characters faced with difficult choices. However, it might also be regarded as emblematic of the perception of a Jew during the war: as someone immature, in need of guidance and help from the ‘locals’, and who, if deprived of their assistance, would perish. Moreover, on each occasion the Jewish youngster is played by a foreign actor, Hungarian Csongor Kassai in Divided We Fall and Polish Michał Sieczkowski in Spring of Life. This fact gives the impression that the Jewish character is somewhat foreign to the native Czechs or Slovaks. That said, in Spring of Life Leo identifies himself as a Pole rather than as a Jew – hence the need to use a Polish actor who speaks Polish. Both Kassai and Sieczkowski are of slight build, conforming to the stereotype of a ‘refined’ or ‘feminized’ diaspora Jew. This differentiates them from non-Jewish males, who come across as taller and bulkier. We often see them bent over, which in the case of Leo results from him pulling or pushing heavy objects; this being a sign of his subaltern status within Nazi society.

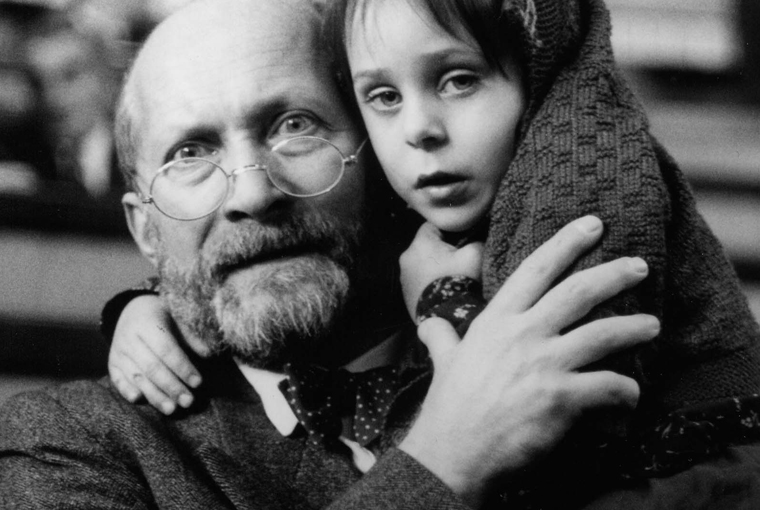

Unlike the two films discussed earlier, Marta and I was directed by a Jewish filmmaker. It contains two male Jewish characters: the fourteen-year-old Emil, who at the beginning of the film lives in Prague, and his much older uncle, Ernst, who lives in Germany. Emil is given the role of a narrator whose attention is focused on Ernst. The uncle attracts and fascinates the teenager, largely because, unlike Emil’s intolerant and authoritarian parents, he treats Emil with a sympathy and understanding afforded to adults. He introduces the boy to the secrets of male-female relations, allows him to drink alcohol, and is sincere in his relations with him.

Ernst comes across as a cosmopolitan bon-vivant, a model European. He enjoys good wine and good food, has a large collection of books, including albums with reproductions of masterpieces of European art, and plays classics of Baroque and Romantic music on a small organ. Despite his advanced age (Michel Piccoli, who played Ernst, was in mid-60s at the time),he is still charismatic and virile, as testified by having a young and beautiful wife and by practicing his profession – gynaecology, even being regarded as a master in his profession. However, when he catches his wife with a young lover, he gets rid of both the lover and the wife, and marries his maid, the eponymous Martha, who is German. Ernst’s cosmopolitan taste epitomizes the multiethnic and multicultural Habsburg Empire, whose political structure and culture were destroyed in the two World Wars. Weiss reconstructs the culture of the Empire with great tenderness – everything that surrounds Ernst is rendered beautiful, yet healthy, like the vegetables Martha collects in the doctor’s garden. This way, Weiss counteracts many stereotypes of (diaspora) Jews as being weak, passive, puny, and emasculated, yet lecherous and decadent.

Ernst’s relationship with Martha is a testimony to his lack of ethnic and class prejudices, confirmed also by the fact that his previous wife was Hungarian. Their relationship can be seen as a symbolic reversing of the typical relation between a Jew and a (non-Jewish) European, where the Jew has to conform to the existing culture – gain dignity and recognition by renouncing difference. Ernst is the Pygmalion to Martha’s Galatea, who meekly accepts whatever changes Ernst imposes on her – dental treatment or buying new lingerie and hats. Of course, in this sense Weiss breaks a taboo, tacitly accepted by Polanski, that Jews should not disturb the existing social order. At the same time, by making the provincial Martha comply with his tastes, Ernst metaphorically takes ownership and leadership over the Habsburg culture.27

When the war breaks out, Ernst leaves Germany for Prague, taking his bride with him. There Ernst and Martha find that their respective families are prejudiced against them. Emil’s mother and her sisters find Martha too simple to fit their middle class milieu, and Martha’s family despise Ernst for being a Jew. Yet the bigotry of their families does not jeopardize the couple’s happiness, only Hitler’s annexation of Czechoslovakia does. Then we witness a similar situation as in Spring of Life and Divided We Fall – a Jewish man becomes endangered, and his survival depends on the help of the non-Jewish community. However, Ernst does not accept the role of victim that history has prescribed to him. He overcomes his circumstances by focusing on rescuing Martha rather than himself. At his instigation, Martha is kidnapped, which saves her from death in the concentration camp. In this way he behaves as a hero. Martha, however, does not accept his sacrifice and most likely commits suicide. In this way Weiss, like Polanski, presents a Jew and a German as equal victims of Nazism, in this way tacitly denying the former a right to be recognized as a privileged victim of a Holocaust.

As in Divided We Fall and Spring of Life, the Jewish character is played by a non-Czech actor, Michel Piccoli. The reason is not to convey his foreignness, but rather charisma and cosmopolitanism – Piccoli epitomizes virility and Europe. Moreover, Piccoli’s foreignness is neutralized by the fact that his partner is played by a German actress, Marianne Sägebrecht, yet with a distinctively international profile. Together they do not represent different nationalities but rather specific attitudes – virility and strength of character on the side of Ernst, warmth on the side of Martha, in a way circumventing national stereotypes.

The fact that Ernst exceeds in stature the Jewish characters in all of the films discussed in this essay might be attributed to the fact that its director was both Jewish and himself represented the cosmopolitan culture associated with the Habsburg Empire. In what was his last film, made at the age of almost ninety, he clearly wanted to create a paean to the Empire, whose cultural richness resulted from embracing people of different ethnicities, who culturally and literally mixed and hybridized, creating its rich culture. The Habsburg Empire stands for the old Europe, which the two World Wars destroyed, but can be viewed as a model for the new, post-Berlin Wall Europe, which Poland and the Czech Republic were eager to join, with its somewhat contradictory – and hardly devoid unproblematic – program of embracing both unity and diversity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I would like to point out the main similarities and differences in the representation of Jews in Polish and Czech post-communist cinemas. The similarity pertains to a preponderance of depicting “non-Jewish Jews” that gain recognition from the ‘natives’ thanks to being like them, even exceeding them in approximating a European ideal due to their being well educated, non-religious, non-nationalistic, non-political, and gentle. Consequently, the films at hand, with the possible exception of Weiser, advocate recognizing Jews as members of a larger community of Poles, Czechs, Europeans or even humanity at large, rather than as belonging to an ethnically and culturally distinct group of Jews.

Yet, the level of assimilation into non-Jewish culture is higher in Czech and Slovak than in Polish films, as demonstrated by the fact that in Polish films there are no sexual relationships between Jewish men and non-Jewish women, which happens in all Czech and Slovak films considered here. This might be seen as an indication of the difference of the actual assimilation of Jews into the respective cultures, with Czechoslovakia, the Czech Republic and Slovakia being more influenced by the multicultural ethos of the Habsburg Monarchy than Poland. Equally, this difference can be seen as a measure of a different approach to the issue of recognizing the Jews in Poland and the Czech Republic. In the first country we observe a shift towards recognising the Jews as a minority group, deserving special privileges; in the Czech Republic, this appears to be less the case.

Author’s note: I would like to thank Elżbieta Ostrowska for her helpful comments and suggestions

Leave a Comment