Identity politics take up a prominent role in the Caucasus, where national and ethnic boundaries have forever been in flux. Though the definition wars which they entail are most commonly associated with nationalist politics, they also take place in scholarly debates, where the claim to a cultural, ethnic and national identity is often perceived as a universal value, if not a human right. Film reviewers thus often describe characters and social groups from movies who lack a pronounced identity as suffering from an inherent detriment which they consciously or subconsciously seek to annul or compensate for. This tendency accords more importance to homogeneous identities than is necessary, suggesting that one cannot be happy without having an abstract, super-individual personality to refer to.

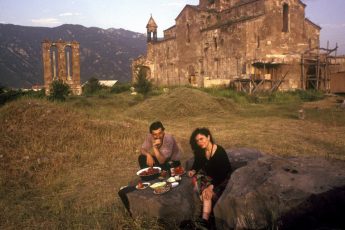

This has been the fate of Atom Egoyan’s Calendar (1993), a film about a Canadian-Armenian photographer whose marriage disintegrates when he travels to Armenia with his wife, and there are other cases in which characters’ personal and interpersonal conflicts are reinterpreted so as to match theories of identity trouble, even though their struggle may predominantly lie somewhere else. Recently, the editors of this journal have stumbled upon an article reading Man of Marble in a perspective of identity politics, though the protagonist of Wajda’s classic appears to struggle with about everything – censorship, propaganda and political corruption – but her national identity. To top it all, another scholar recently framed Corneliu Porumboiu’s Police, Adjective (2009) in terms of identity politics, the conflict of the main character apparently being one of not being being able to identify with democratic Romania (really).

While nationalism and nationhood are certainly a recurring theme in many Central and Eastern European films, they regretably have turned into a sort of default explanation for all kinds of catastrophic experiences. Not all sectors of life – love (Calendar), political oppression (Man of Marble) or moral doubts (Police, Adjective) -, however, are likely to conflict with one’s national identity. The obvious risk of claiming that they do is the suggestion that people with different nationalities wouldn’t have these conflicts. It also seems to imply that the solution to such conflicts could be provided by some alternative identification or the abandonment of one’s identificatory problems (hail transnationalism!). Many conflicts in cinema have personal explanations, some have communal explanations, and only very few have national ones. But all of them have universal implications. Readymade theories about national identity rid cinema of its universal appeal.

***

Moritz Pfeifer critically examines the aspects of identity politics in Atom Egoyan’s Calendar, advocating an existential reading of the film’s main conflict. Konstanty Kuzma tries to explain the appeal of Temur Babluani’s forgotten The Sun of the Sleepless, a seamless 1990s Georgian classic, while Anna Batori saw Levan Koguashvili’s contemporary Street Days, another Georgian film indirectly dealing with that difficult time in the country’s history. Moritz Pfeifer also lauds the dream sequences in Ilgar Safat’s The Precinct, though he ultimately criticizes the film for resorting to tried and tested neorealist techniques which seem to dominate today’s landscape of Azerbaijani cinema. Meanwhile, Colette de Castro completes our coverage of the Karlovy Vary IFF with a review of Gyula Nemes’ Zero (2015), a controversial film about ecology.

Konstanty Kuzma & Moritz Pfeifer

Editors

Leave a Comment