Paradjanov’s Interrupted Project

Sergei Paradjanov’s Kiev Frescoes (Kievski Freski, 1966)

Vol. 103 (March 2020) by Anna Doyle

During the period known as the Thaw in the Soviet Union, and into the Brezhnev era, many films were either banned outright or purposefully under-distributed. At the time, it was easier to get around the Soviet censorship system if a film had a nationalistic theme or subject, thus those who wanted to experiment formally often used the ruse of associating nationalist themes with their poetic experiments. This was not only in the way they brought together folk costumes, archaic myths and national rites. It was also necessary to show recent events that foregrounded Soviet greatness, such as the Great Patriotic War. This was the case for Sergei Paradjanov’s film Kiev Frescoes (Dovzhenko Film Studio, 1965-1966).

The film was commissioned by the Soviet Ukrainian government, who wanted Paradjanov to make a nationalist film to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Great Patriotic War – as the conflict between the USSR and Nazi Germany is still known in Russia today -, that had ended on May 9, 1945 with the liberation of Kiev from the Germans. Commemorating the Great Patriotic War was a way for official ideology to celebrate Ukrainian nationalism within Soviet internationalism, as it was understood at the time; in line with what Stalin called “nationalist in form and socialist in content”, namely that Ukrainian nationalism could only exist within a socialist Soviet empire (and not as a “bourgeois” liberal nationalism that had emerged in the liberal countries of the West). Stalin claimed that “proletarian culture does not abolish national culture, it gives it content, and conversely national culture gives form to proletarian culture”, adding, “our goal is to bring all the peoples of the Soviet Union together in communist unity, Soviet unity, in order to forge a Soviet man enriched by his popular culture but delivered from that nationalism which is only the manifestation of bourgeois interests”. The promotion of this ethnic nationalism in line with socialism thus became the rule of socialist realism for the Goskino censorship system, active during Paradjanov’s film career. The Great Patriotic War was part of the ideological discourse of the time, as historian Yuri Slezkin writes, “The Great Patriotic War was followed by an ex cathedra explanation that class issues were secondary to ethnic issues, and that the promotion of nationalism in general should be a sacred principle of Leninism Marxism”.1

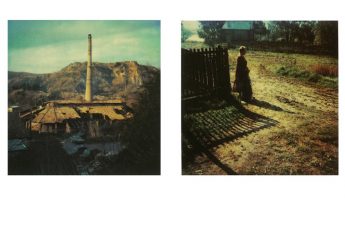

The censorship of the film Kiev Frescoes by the Russian Goskino marks the beginning of Paradjanov’s notorious oppression. In 1965 he was forced to abort his feature that he had planned to make 80 minutes long, and to reset the remains of the project into a short 13 minute film completed in 1966.2 This film, done in a totally new style from his preceding feature, The Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, plays on discontinuous editing and disruptive themes, asserting a kind of impossibility of creating narrative links. Paradjanov’s first idea was to make a film that examined contemporary life in Kiev, like a Ukrainian version of Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera. He opened his first script with the legend “I have conceived the film as Cinefrescoes/kinofreski”3.

In an issue of the journal Iskusstovo kino, film critic E. Levin describes the original scenario as “outwardly chaotic, incoherent, rhythmic, film-imagistic prose, more precisely, a romantic ballad for the screen, set forth in metaphors that are subtle, whimsical, often difficult to catch or, better to say, a lyrical wistful film-poem suffused with light”4. In the original screenplay, Paradjanov uses characters from the Patriotic War: soldiers and a war widow. It was supposed to be set on the day of Kiev’s liberation around a museum, where a portrait of the Infanta Marguerita by Velasquez was to be exhibited. The administration of the USSR’s Goskino bureau wrote a letter in June 1965 to the Goskino of Ukraine about the film, praising its pictorial and symbolic aspects, but stating that the film does not celebrate the heroism of the Great Patriotic War soldiers. The letter states:

Touching upon such a crucial theme as that of the Great Patriotic War, and this is determined by the choice of characters (the general, soldiers, a woman who lost her husband in the war) and the time of the action (the anniversary of the liberation of Kiev), the author should have introduced, albeit in an associative form, episodes that would speak about the heroism of the Soviet people, about the great feat accomplished by them. Unfortunately, this is not in the script so far. To not talk about it means to say nothing about the Great Patriotic War.5

The letter also criticizes the absence of human speech in the script, as well as the hermetic symbolism that makes the film inaccessible to the general viewer, “the excessive encodedness of a number of episodes”6. Thus, if the Ukrainian Goskino authorized the film to be made, the Moscow Goskino, as we can see, was more reserved and critical toward the film. Ivan Drach, a poet, founder of the “new wave” of Ukrainian poetry, and a friend of Paradjanov, helped the director to rewrite his screenplay by adding poetic images that would have a direct link with the Second World War. Nevertheless, the script was not retained.

In the thirteen-minute film, Paradjanov left his first script aside to create an innovative film that has even less to do with the Great Patriotic War than the project that was to be aborted. It comes across as a romantic and poetic exploration of Ukrainian ethnicity in the surrealistic form of a pantomime, without dialogue and sometimes employing hermetic symbolism. Paradjanov, speaking of his film, once made, described it as follows: “When the romantic fuses with the everyday, the everyday with the private, the epic with the details, the sum total amounts to film-poetry”7.

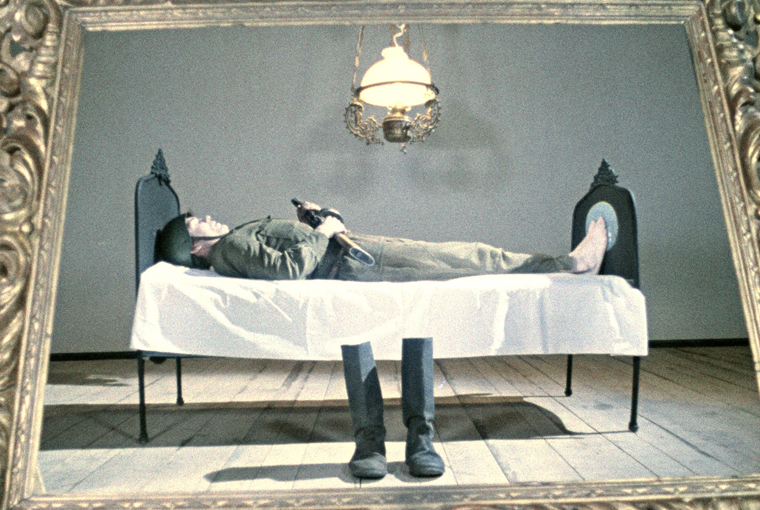

In this version of the film, silent objects, like an iron or a Singer sewing machine, reinforce the reification of human figures that appear as pantomime characters. Paradjanov’s models are often pantomimic – icons, religious frescoes, and miniature paintings. Three soldiers symmetrically situated on the screen take their boots off and clean the floor somewhat like in a Caillebotte painting. One of the soldiers is then shown dreaming of female hair. A naked woman appears, full-frontal nudity which was very scandalous in the Soviet Union at the time, indeed Tarkovski’s Andrei Rublev had been shelved until the early 1970’s for this specific reason.8 One can see a decomposed piano that is accompanied by non-diegetic out of tune traditional music mixed with a tune by Charles Aznavour, the famous Armenian pop singer. A shell appears, probably symbolizing the feminine sexual organ and foreshadowing the presence of the shell in The Color of Pomegranates. A young child plays with the golden frame of a painting: Paradjanov always compares his own vision to that of a child.

An ashugh9 with his instrument appears in the film, a self-reflexive figure, who functions as a metanarrative sign of the presence of the filmmaker as poet. Paradjanov’s theme of eroticism in the absence of contact is also present in the film. Not only is love a fantasy for the soldier (as he is dreaming of a woman’s hair), it is aborted love that seems to be central, fitting with the theme of discontinuity. This is shown by the presence of the engagement ring held by a man and his ex-wife, followed by a shot of an empty cradle, around which the couple is dancing, suggesting that no child has come out of this marriage. The cradle is an object Paradjanov will use a lot in The Color of Pomegranate, in the dream sequence especially, simultaneously symbolizing lost childhood and aborted love.

Consequently, the nationalist and positivist vision of history that was to be commemorated here is abandoned for an experimental vision of Ukrainian identity that tends to lose the viewer in formal experimentation rather than give them historical landmarks. The absence of narrative continuity appears to be the only way to account for the real-life discontinuity in the history of non-Russian republics and thus to break down the legendary fabric of Soviet myths of origin. Paradjanov’s project goes much further than a simple commemoration of the war. It shows, almost in the manner of Fellini in 8 ½, the imaginary and inner vision of contemporary life in Kiev. In Kiev Frescoes, movement is static and works through cine-tableau, it creates still lives where objects are exchanged and circulate. The work becomes a form of anti-narrative cinema using paratactic editing.

Paradjanov thus builds a self-sufficient space marked by the absence of off-screen shots, where spatial and temporal categories that have been considered heterogeneous since the invention of perspective in the Renaissance, here intertwine: the inside and the outside (we see the inside and outside of a palace, the visible and invisible face of it), or, the past, present and future (events of successive times are present synchronically). In Paradjanov’s work, it is striking to systematically find these elements within the perspectivist space inherited by cinema, as if to make a connection between post-Soviet and pre-Albertian space. Paradjanov’s double refusal is that of narrative continuity as well as of accuracy in historical reconstruction.10 In addition to national history, the heritage of the Caucasian arts is at the center of Paradjanov’s political and aesthetic questioning. All his subjects, his music, the aesthetics of his frames, even the objects and architecture of his sets are borrowed from the culture and traditional arts of the Caucasus. Nevertheless, Paradjanov claims to be, not so much an heir to tradition, or an agent of mimesis, as an artist fighting for the survival of folklore and of objects outside of the museum gaze. Paradjanov claims in his essay “Perpetual Motion”: “I wanted to convey a ‘folk vision’ without museum greasepaint – to return all these stunning embroideries, reliefs, tiles, to their creative source, to combine them in a single spiritual act’’.

References

References

- 1Yuri Slezkine, The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism Slavic Review, Vol. 53, No. 2 (Summer, 1994), pp. 414-452.

- 2James Steffen, The Cinema of Sergei Paradjanov, The University of Wisconsin Press, 2013, p.88.

- 3James Steffen, The Cinema of Sergei Paradjanov, The University of Wisconsin Press, 2013, p.90.

- 4Ibid.

- 5James Steffen, The Cinema of Sergei Paradjanov, The University of Wisconsin Press, 2013, p.101.

- 6Ibid.

- 7James Steffen, The Cinema of Sergei Paradjanov, The University of Wisconsin Press, 2013, p.89.

- 8James Steffen, The Cinema of Sergei Paradjanov, The University of Wisconsin Press, 2013, p.108.

- 9A medieval Caucasian bard.

- 10Sylvie Rollet « Paradjanov : ‘Caucase, mon beau souci’ : continuité et fragmentation », in Le Septième art , dir. J. Aumont, Paris, Léo Scheer, 2003, pp. 213-225.

Leave a Comment