Together but Apart

Family Dynamics in Cristi Puiu’s Sieranevada (2016)

Vol. 127 (September 2022) by Ioana Tarbu

Sieranevada (2016) is the third installment of Cristi Puiu’s Six Tales from the Outskirts of Bucharest series, in which the filmmaker retraces Romania’s moral crisis as the country struggles to escape the grip of Communism. Starting from Puiu’s statement that Sieranevada was made having in mind a Romanian-language public,1 this essay looks at how the film achieves a sense of cultural intimacy and connivance with the public. It does so by exposing aspects of embarrassment and vulnerability that the viewers can recognize and identify with, thus reactivating their sense of community and cultural belonging that is otherwise shattered in post-Communist Romania.

The First Two Scenes – Preamble to the Story

A medium shot of a narrow, crowded, noisy street corner in downtown Bucharest: trolleys, taxis and courier cars pass alongside passengers; a man is trying to park his BMW and, for lack of space, he leaves it in the middle of the street; a DHL truck soon finds itself caught behind the BMW, and the driver starts laying on the horn; random graffiti scribblings cover the building on the street corner, and a construction tape around the adjacent sidewalk warns the passers-by of a “Danger of explosion” (Figures 1&2). This first scene of the film is made up of a single long take that lasts for almost seven minutes. The camera is situated at eye-level, and the medium shot ensures that there is a sufficient distance from the actors so as to prevent us from making out what they are saying given the abundant background noise. Things have been happening for a while before we can get a surreptitious glimpse of the universe the individual characters inhabit.

Aesthetically, this style of filming is important for two reasons. Firstly, it positions the film in the realistic tradition of observational cinema used preponderantly by Cristi Puiu, Cristian Mungiu and Corneliu Porumboiu. The long takes and the relative lack of editing and close-ups help outline an aesthetic which does not highlight the action of the story, but instead frames the action as an excerpt from an uninterrupted flow of everyday life. If not immaterial, the action of the story is at least secondary to the feeling that is conveyed as the viewers watch this slice of life and gain access to its immediate texture. Secondly, Puiu’s cold open narrative technique, which throws viewers directly into the flow of the action, suggests an exemplary story, not an exceptional one – we are presented with a story of the ordinary rather than the extraordinary, both in terms of characters and of circumstance. The technique is quite typical of the New Romanian Cinema, whose narratives capture everyman and everywoman in situations that have been unfolding for a while. This particular scene, which precedes the opening credits, also anticipates the main themes of the film. The chaos of the street with its disorderly traffic and the construction work all around defines a world whose main mode of existence seems to heavily rely on sensorial overload and makeshift solutions, a world where people do what they can to get by. Puiu nevertheless stays away from the miserabilist view of the Communist dilapidated apartment buildings that have become a house brand not only of Romanian cinema after ’89, but also a fetishized image of post-Communist Eastern European cinema in international film festivals. In fact, little of the city comes center-stage in Sieranevada – certainly less than in his previous Aurora (2010), for example, whose stores, kiosks and railway tracks, all of which the protagonist frequents, are urban landmarks of the downtown and of the outskirts of Bucharest.

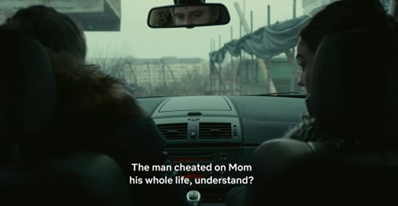

The hostile environment from the street is translated to the inside of the car in the next shot. This is the second scene that prepares the ground for the rest of the film. In watching the heated discussion between Laura (Cătălina Moga) and Lary (Mimi Brănescu), we plunge into a world of conflict and prejudice, self-seeking interests and little dramas consumed within the enclosed space of the car and set against an equally agitated outside. The traffic jams, the rows of apartment buildings, together with the series of excavator tractors that succeed one another in front of the dimmed windscreen of Lary’s car, complete the picture of the city. Puiu adopts a rather horizontal perspective on Bucharest, one that perceives it as an entity fleeting by the window and thus adding a dynamic quality to the otherwise heavy, old, and oppressive space of the neighborhoods. This perception of the city as a mobile itinerary, frequently met in the films of the New Romanian Cinema, turns it into a part of the flow of experience, of some situations that have been unfolding before the film even begins. This horizontality and the agglomeration of details further translates into the enclosed space of an apartment through the camera panning left and right, as Laura and Lary arrive at their destination, and we are made privy to a family reunion.

The Gaze of the Camera and Competing Subjectivities

The main event around which the film is structured is a family gathering intended as a commemorative dinner. The event includes a memorial service to be officiated, following the Eastern Orthodox tradition, by a priest. Most of the film shows the characters shuffling from one room to another during a little less than three hours of tireless conversations that sometimes degenerate into conflicts and almost always betray muffled tensions. Due to the film’s centering on an act of waiting and an indefinitely delayed feast – only after the priest arrives, can the family gather around the table to eat – critics have likened its plot to Samuel Becket’s Waiting for Godot and Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie.2 The camera is often placed in the central hallway of the apartment, a quasi-dark and narrow space that is situated at the intersection of a few rooms and their closed doors. From this position, it can watch stealthily whatever comes before its eye-level lens, whether it’s a silhouette or someone’s legs, like a secret guest who can only have limited access to the apartment. Due to its position in a space of transition, sometimes the camera is a prisoner of its own intermedial condition, waiting for a character to give it access to one of the private spaces of the apartment. This style of filming that foregrounds partial access ceases to be voyeuristic and invisible. The viewer is constantly aware of there being a camera recording the action on screen. This awareness prevents identification with the characters, since oftentimes the viewers can only see image fragments instead of the entire picture, and are thus never completely drawn in the space of the apartment. The de-voyeuristic gaze allows us to recognize both our worries and our idiosyncrasies in those of the characters, and to perceive them as amusingly familiar, just as the man in whose memory the feast is held might view them.

In Puiu’s aesthetics, the camera is not only not omniscient, it is literally anthropomorphic. In an interview published on MUBI, Puiu said that he decided to use and build on the technique developed in Aurora, which involved putting the camera on a tripod and moving it as far as a human head can move, without any tele-objective, zooming or change in the focal length. The camera in Sieranevada uses “the same eyes as the eyes we are born with”3, a statement that should obviously not be taken literally, but rather as referring to the camera’s lack of omniscience, limited as it is to human-like observational abilities. It lingers in the hallway and in various corners of the apartment, going back and forth like an uncomfortable bystander, sometimes lingering in doorways, at other times inside the rooms. Through the camera movement and the angles from which he shoots the scenery, director of photography Barbu Bălășoiu tries to mimic the gaze of the departed paterfamilias contemplating the lives of his family members from an intermedial position. To this effect, the characters are sometimes filmed contre-jour, like shadowy silhouettes, each inhabiting their own little bubble of tenuous convictions and certainties (Figures 3&4). Their occasional appearance as spectral silhouettes highlights the vulnerability and ephemerality of their position in this world – as seen from the dead man’s perspective – as well as the solipsism of their views and beliefs.

Truth rarely lies in people’s utterances, but rather in-between the lines, in their behavior and reactions, and in the tension that is created in the small spaces they inhabit. The filming technique helps convey this idea. The panning movement of the camera, which follows the back and forth of the characters, creates a sense of horizontality, which László Strausz identifies as a fundamental perceptual trope of the film, “illustrating how the bewildered camera barely scratches the surface of the recounted events while it attempts to locate their significance”.4 This horizontal movement reflects the choreography of the characters’ movements and the various stories they tell to make sense of the world around them, which oftentimes contradict one another. The impression given by the panning camera is different from the horizontality of the fleeting urban landscape as recorded from inside the car in the opening scene, but it is still a movement that hovers on a flat plane, suggesting the leveling of historical accounts and personal opinions, and the elusiveness of truth.

The conversations on politics and the events of the day gradually outline the diverse points of view on history and suggest that people’s own stories and interpretations, the versions loaded with their personal beliefs and perceptions of an event, are what creates history. The men that discuss the involvement of governments in supposed put-up jobs like 9/11, the Charlie Hebdo attacks – which happened three days before this family reunion – and the fall of Communism, are all part of a generation that was in their early or mid-teens during the ’89 Romanian Revolution. In school and during the two hours of daily television broadcast before 1989, they were told they were living in a Golden Age, the age of a New Man and a New World. After the fall of the Communist regime, that same view was repudiated and exposed as an appalling and intolerable lie on the same television channel and in the very same schools. Overnight, history was fundamentally rewritten. Sebi’s (Marin Grigore) paranoid scenarios, Gabi’s (Rolando Matsangos) insistence on his eyewitness testimony, or the fear that prevents one from taking action, which Relu (Lary’s younger brother, played by Bogdan Dumitrache) articulates with the assurance of a military man, are all expressions of attitudes and mindsets that derive from this brutally schizoid making and unmaking of history.

When the camera pans towards the kitchen, a different exchange of opinions is foregrounded. After the more or less casual dialogues carried out in the dining room, we plunge right into a bitter discussion about the Communist era between Sandra – Lary’s younger sister, a woman in her thirties – and Evelina, an elderly woman who seems to be a long-time friend of the family. Here, two opposite views of what Communism meant for the country collide. Having spent most of her life under Communism, Evelina (Tatiana Iekel) not only extols the ideals of the regime. She also directly identifies with the Communists when she says that “we fought for a better world”, “we drove out the fascists”, “we brought electricity to people’s homes”, etc. Her discourse unfolds on quite dispassionate grounds as she enumerates the benefits that she thinks the Communist regime brought to the post-WWII population. Sandra (Judith State) on the other hand is extremely emotional throughout the conversation: she bursts into tears while going about the chores in the kitchen and throwing her angry replies. She condemns the villainy of the regime by almost shouting out how Communists indiscriminately imprisoned and killed innocent people that either belonged to the intelligentsia of the time, or to the working class. Her emotional outburst not only suggests that she is deeply aware of the enduring effects of this trauma in national history, but also that she partially embodies these effects.

The two women carry out their repartee on adversarial positions – standing instead of sitting. This repartee is no longer about casual personal opinions or about who is more knowledgeable or more informed. It is about what people stand for and, more profoundly, about the different histories imprinted on people’s minds, bodies, ways of being and behaving. Take, for example, the white fox fur hat that Evelina is wearing (Figure 5). While it may be a common symbol in many American period movies for Russian women, it was also very popular in Romania during Communist times. It looked imposing, and it was one of the possessions the working class and party cadres shared. It has since become an image of Communist backwardness, for which the younger generations in Romania have developed a particular distaste. Evelina keeps wearing the hat inside the house, which makes her and the ideology she stands for even more conspicuous. Guardians of pre-1989 revolutionary cultural memory, the people of her generation are sidelined by history as they become increasingly redundant in the new political and social order.

When religion comes up in this discussion, it is in Evelina’s Marxist view as “the opium of the people”. She believes all churches should be shut down because they rip people off, and, in a less dispassionate retort, she spouts that priests should be thrown in jail as well. The confrontation between Evelina and Sandra is the confrontation between the Communist point of view and the neoconservative-liberal one, which many educated young Romanians adopted after 1989 as a stance developed in response to the wrongs of a totalitarian regime. Katalin Sándor draws attention to the space in which this discussion takes place in the film: the “postcommunist view on the ideology of communism and the relationship to the achievements of communism” is a thorny matter that must remain hidden behind the kitchen door.5 The kitchen becomes a repository of past suffering, as it is the most hermetic space of the house, whose door must stay closed at all times – Sandra’s repeated gesture of closing it puts particular emphasis on this circumstance.

The differences between the manner in which the discussion on the 9/11 attacks is carried out and how that on Romania’s legacy of Communism is conducted, are quite obvious. The first is treated as a rather benign obsession entertained by Sebi, to which the others retort with amusing or casual counterarguments, while the second is treated as a wound if not a national trauma. By bringing competing discourses and subjectivities together and recording them as they unfold in front of the camera, Puiu succeeds in conveying a sense of what is more distant and what is closer and more traumatic. The ideologies that the characters debate and embrace, and their own beliefs, whether they’re royalist, like Sandra’s, or Communist, like Evelina’s, phlegmatic-conformist (Lary) or skeptical-paranoid (Sebi), underscore the basic ambiguity of the historical events’ significance. They also “prevent one from seeing the world and seeing the other”, in Puiu’s words,6 an idea which is also suggested by the uneasiness of the gaze of the camera and the shadowy silhouettes.

However, despite their schematic portrayal, the characters do not appear to be lacking depth. Puiu’s observational cinema invites the viewer to see competing sides of the same person, which makes it difficult to side with one character or another. The film situates the viewers on a higher plane than that of mere identification or partisanship, facilitating an understanding of the characters through their inherent heterogeneity and hence, through their humanity. The conspiracy theories that Sebi endorses may betray a mind prone to paranoia and attracted to spectacular explanations, but they also point to the difficulty of living through the uncertainties related to the major events in one’s collective history and, in the case of the 1989 Revolution, they suggest the void in coherent national explanations. When Sandra laments the atrocities the Communist system perpetrated against innocent people, one is tempted to side with her humanistic outlook. Seconds later though, she splutters an anti-Semitic cliché when she mentions “Marx, Lenin, and other notorious kikes”.7 Such contradictory attitudes prevent us from jumping to conclusions or formulating a stereotypical opinion about the characters, as Puiu constantly reminds us of the complexity and ambivalence that is integral to being alive.

Cultural Intimacy

Gathering the characters around the table and showing their behavior in conversation has always been the perfect occasion for a study of mores and mentalities. Through the family reunion, Sieranevada holds up a mirror to society after its twenty-six-year process of transitioning to a global cultural and economic order. The coexistence of traditional patterns of masculinity, for instance, and new socialization forms and mindsets are visible all throughout. Infidelity is a traditional masculine practice still very much prevalent among most of the men who are at the gathering, and women have to find ways to either put up with it or confront it. This age-old reality coexists with fresher mentalities that speak of the country’s opening to the world outside its own borders. The cosmopolitan preoccupation of going on vacations in Bangkok, as opposed to sojourns to nearby Greece, which have become too monotonous –“It’s like going to work,” Laura complains – makes these recent frames of mind apparent. The vivid disagreement about the differences between Tom-Yum and Kha-Gai Thai soups, in which two characters are engaged early on, is another example of the changing mental maps and local realities. Despite its rather trivial content, the conversation is evidence of increasing cultural openness. Lary is a doctor by training but works as a commercial distributor of medical equipment, since in a post-Communist country that is being transformed into a neoliberal economy, being a distributor is more profitable. However, if local politics and the economy have changed, ancient forms of paying respect to the memory of the departed are still valued. Rituals for keeping the community together are still in place, even if performed less substantially by the younger generations. All these facts point to a reality in flux, where the old coexists with the new in ways that are difficult to define, predict and sometimes even make sense of.

Traumas and shared histories are buried deep, but their effects come out unexpectedly in casual conversations or in silent interactions, and they represent the common ground on which people bond, creating a cultural intimacy both within the filmic fiction and outside of it, with(in) the audience. Anthropologist of post-socialist transitions Michael Herzfeld explains that cultural intimacy captures “those aspects of a cultural identity that are considered a source of external embarrassment but that nevertheless provide insiders with their assurance of common sociality”.8 Herzfeld points to a “rueful self-recognition” and an “inward acknowledgement of cultural intimacy”9 that occurs when people recognize certain features that belong to them as members of a particular culture with a specific shared history, especially a marginal or minor culture. A form of intimacy takes shape through this recognition of shared vulnerabilities and collective traits. This form of intimacy is something that theoretical works on nationalism, with their top-down view, cannot render but that artistic products, with their focus on everyday characters, incidents, and settings, are able to encapsulate. It can generate two attitudes as far as consumers of such art are concerned: a defeatist kind of acceptance (‘this is how we are as a nation, there is nothing we can do about it’), which considers the things presented as defining traits or stereotypes, and an angered rejection that is shared by viewers who feel offended that a community’s dirty laundry is being aired for the entertainment of audiences at international film festivals. One viewer expressed his opinions in line with the second attitude during a public screening of Mungiu’s first feature Occident (2002) in Paris. He exclaimed: “You shouldn’t expose people’s lives on screen like this! Do you know us from somewhere?”.10 Regardless of whether they accept or reject these portrayals, Romanians engage with them in a personal way, as people with a shared history and culture do. Puiu’s Sieranevada activates this cultural intimacy for the audience by allowing them to engage with these forms of self-recognition. This engagement requires a deciphering spectator who is able to read the elements of the mise-en-scène – the materiality of the space and its cultural specificity – but also to relate to their significance.

Puiu points to the importance that “a look, a just timing, a gesture, a word here and there” have, as they represent ways in which “glimpses of the ineffable” can be conveyed.11 In an early scene of Sieranevada, a woman is carrying a large pot of sarmale12 from the apartment across the hallway to the apartment where the commemoration takes place; the Eastern European viewer can easily understand the implications of this gesture as a reminiscence of Communist times, when people would help each other in times of penury by borrowing certain ingredients or resources (like the use of the oven, in this case) from each other. This practice of neighborly socialization for very practical purposes is a reminder of Communist-era habits and mores, whose collective character is still perpetuated by the elderly in a culture that is otherwise largely individualistic. The texture of everyday interactions comes out through these small, apparently insignificant gestures, which contribute to a more concrete perception of intimacy by the viewer and render the experience of watching the film more immediate. Sieranevada – just like Puiu’s previous works Stuff and Dough or The Death of Mr. Lăzărescu – is a keen testimony to a form of intimacy that can best be communicated through a mixture of dialogue and gestures that reflects a shared social and cultural history.

The Construction Site

The fight over the parking spot towards the end of the film speaks of an issue that has become more and more pressing in Bucharest: the overpopulation of the urban space, a development that was not foreseen by Communist urbanization plans. Apartment buildings were intended to house as many people as possible in a limited space, more in the form of dormitories than as units that allowed for the development of an organic urban community. Also, the Communist urbanization project took into account a pedestrian working population and not one of car owners. After 1989 however, as the population’s access to apartments and cars increased, the streets became more crowded, traffic jams became more frequent, and people turned more aggressive.

In the confined space of the car and visibly shaken by the confrontation with a neighborhood thug (Andi Vasluianu), Lary tells Laura of a childhood incident involving his younger brother Relu (Bogdan Dumitrache), who was caught smoking by his father. Relu came up with a childish story to explain himself – a thief had come to the house and forced him to smoke – which his father did not question. Remembering how his younger brother managed to deceive his father with such an obvious lie, Lary wonders how dishonesty can coexist with credulity. How could his father, who had been cheating on his mother throughout their marriage and was skilled at telling lies, be so gullible when it came to his ten-year old son? Then he suggests that, just like his father, he has also been unfaithful occasionally. Lary’s sudden impulse to confess his infidelity in the claustrophobic space of the car does not lend itself to an easy reading. His story counters the atmosphere of the self-absorbed family reunion, which is oblivious to the departed and the embedded realization that the living tend to the living.13 The incident that Lary recounts is the only instance in which the father is remembered in a story that brings his memory to the fore. It also speaks of an entire collective history, where families had to stay together and were kept whole by appearances and lies. Divorce was not an easy option during Communism – on the contrary, it was heavily discouraged, and the procedure was made cumbersome by a system whose goal was building large families from which a strong working-class population would emerge. Part of the trauma that transpires in Lary’s confession has to do with this particular collective history, in which secrets, subterfuges and lies are embedded in the everyday life of families. Duplicity was of course a fact of life outside the family as well. It was a universally accepted norm in Romania at the time for people to say one thing and believe another, since all expressed opinions had to conform to the doctrine of the Party and dissent was severely punished. This widespread practice in a society filled with propaganda made one less sensitive to the features that separate truth from lie, which explains the apparently surprising gullibility of Lary’s father. This apparent gullibility points to a form of self-manipulation, an attitude prevalent during Communism, when people often had to persuade themselves of the truthfulness of their lies, a kind of survival mechanism in a totalitarian regime. The split between thought and outright expression created a schizoid national psyche whose remnants are visible in Lary’s account.

The parking lot confrontation seems to also have acted as the trigger of more humble thoughts for Lary, and of a certain reconsideration of the machismo present in many daily interactions. Paradoxically, Lary’s confession of infidelity is an attempt to deny that he is part of a clan of duplicitous men that starts with his father and uncle and continues with the men of his generation, an attempt to distance himself from something that is as entrenched in his way of being as are his social behavior or education. From this point of view, the film is about the revival or restoration of the family through the symbolic instatement of a new paterfamilias in Lary.14 As in any patriarchal society, the family needs a male head who can be called upon to regulate family disputes – an authority figure who can make the law. Lary has his flaws as a father and as a husband, he is inattentive to both his daughter’s requests and to those of his wife, and he is unfaithful. Despite all of this, he mediates the family’s conflicts and appears to be the most trustworthy of all in a world whose everyday reality is in crisis. He is however ambivalent about taking this role upon himself, and his confession of infidelity suggests a refusal to carry on what seems like the tacitly accepted duplicity of the patriarch.

The scene juxtaposes the immediacy of the conversation to the limited access we have to the characters’ thoughts and emotions. Lary and Laura are in the front seats of the car, while the camera films them from the backseat, with partial visibility (Figure 6). This style of filming, in which the camera both observes and participates as a third back-seat passenger, is again a way of denying identification to the viewer, who watches the drama with the uneasy feeling of being a guest to their intimacy. All we can have access to is, at best, partial truths and brief moments that intimate an unexpected connection. If the apartment can be regarded as a metaphor of society, the car becomes a signifier of the self, the locus of a heartfelt confrontation with one’s memory and inner truth. The urban background that can be glimpsed through the windshield functions as a symbolic mise-en-scène. The horizon is blocked by an apartment building, and there are structures under construction both to the left and to the right. The protective scaffolding of the construction site to the right foregrounds a series of high poles which rise through the air like menacing weapons, warning viewers of the dangers related to digging too deep into family traumas and history. The verticality of the urban image in this scene stands in contrast with the horizontality of the city as it is represented in the beginning of the film. Confronting one’s history and memory is a painful process that cuts deep, to the core of one’s being, but the construction site in the background of this scene also symbolizes the hope of rebuilding or starting anew, a process that is often preceded by suffering.

Conclusion

Cinema in the way Puiu conceives of it may not lead to clear-cut solutions and easy understanding, but it can nonetheless show us the way to a life that is more encompassing than we can see and make us aware of how much of it is unknown to us. This is a revelation which classical cinema, with its claims to understanding and controlling the world (or representations thereof), cannot offer. The film’s ability to convey common histories and bonds through the verbal as well as the nonverbal is what contributes to the feeling of intimacy that the film achieves for its post-Socialist audience. Cultural intimacy comes from recognizing these traits and mannerisms, as well as the little details that make up the everyday lives of these characters; they are representative of every woman, man, and family. In these characters, their relations, and the events they encounter, Romanian (and Eastern European) viewers can recognize their inherent contradictions and ambivalence and the necessity of living with them. At the same time, Sieranevada contributes to preserving national memory by paying attention to specific details that make up everyday interfamilial relations.

References

- 1.Rădulescu, M. (Moderator). (2016). Ora de ştiri. [Television programme]. Bucharest: TVR2. Available on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uNlr2U3mNRg [Accessed on 1 April 2022].

- 2.See Cronk, Jordan (2016). “Sieranevada (Cristi Puiu, Romania/France/Bosnia and Herzegovnia/Croatia/Republic of Macedonia)’’, Cinema Scope, no. 67. https://cinema-scope.com/spotlight/sieranevada-cristi-puiu-romaniafrancebosnia-herzegovniacroatiarepublic-macedonia/ [Accessed on 1 April 2022] and Bradshaw, Peter (2016). “Sieranevada review – Food for Thought (But Not For the Mourners) In Romanian Oddity’’, The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/may/12/cannes-2016-film-festival-sieranevada-review-cristi-puiu-romania [Accessed on 1 April 2022].

- 3.Holzapfel, Patrick. (2016). “The Dead Person Is the Camera: Talking with Cristi Puiu about Sieranevada’’. The Notebook. https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/the-dead-person-is-the-camera-talking-with-cristi-puiu-about-sieranevada [Accessed on 1 April 2022].

- 4.Strausz, László (2017). Hesitant Histories on the Romanian Screen. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 230.

- 5.Sándor, Katalin (2017). “From the Back Seat of the Car – Space and Intimacy.’’ Contact Zones. Studies in Central and Eastern European Film and Literature, no. 2, 6.

- 6.Filimon, Monica (2017). Cristi Puiu. Urbana, Chicago and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 132.

- 7.Gorzo, Andrei. “A death in the Family: Cristi Puiu’s Sieranevada’’. https://www.academia.edu/30270768/A_death_in_the_family_Cristi_Puius_Sieranevada_ [Accessed on 1 April 2022].

- 8.Herzfeld, Michael (2005). Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics in the Nation-State. New York: Routledge, 3.

- 9.Ibid.

- 10.Georgescu, Diana (2011). “Marrying into the European Family of Nations: National Disorder and Upset Gender Roles in Post-Communist Romanian Film.’’ Journal of Women’s History, vol. 23, no. 4, 131–54.

- 11.Filimon, 131.

- 12.Romanian traditional dish made of minced meat wrapped in marinated cabbage rolls and usually served for Christmas, Easter and at commemorative events.

- 13.This is an interpretation offered by several critics. Cf. Gorzo.

- 14.For an interpretation that understands Lary as evolving into the new patriarch, see also Monica Filimon’s “And Thy Word Is the Truth’’, Cineaste, Spring 2017, 32.

Leave a Comment