Sokurov’s Lofty Museology

Alexander Sokurov’s Francofonia (2015)

Vol. 59 (November 2015) by Moritz Pfeifer

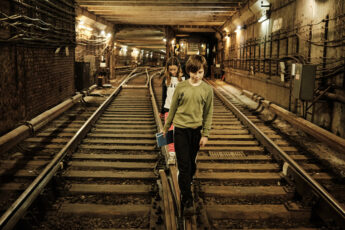

After his tetralogy on 20th century dictators, Sokurov’s new film continues to explore political tragedy, this time through art. The setting is Paris, the Louvre, once said to be the center of the world. Although at times confusing in its free-associative style, the film depicts three distinct historical periods of the museum. First, its beginnings during the French Revolution and its expansion under Napoleon, who pillared a considerable amount of masterpieces during his military campaigns. In a second narrative, Sokurov portrays the museum’s fate under the German occupation during the Second World War, when its treasures were threatened to be relocated to Germany. Lastly, there are few, but nevertheless important allusions to the museum’s role in the perilous setting of contemporary globalization. All three periods lead Sokurov to meditate on the purpose of art and its complex and often corrupted relationship with ownership and power.

The part about the Revolution and Napoleon displays a conflict between the museum’s democratic origins and its subsequent imperial development. Before the Revolution of 1789, the Louvre used to be, along with Versailles, the most important seat of French royalty. But the first Republic turned the palace into the world’s first public museum, making openly accessible a vast collection of art that was hitherto only visible to the noble eye. In Sokurov’s film, these revolutionary origins are symbolized through Marianne (played by Johanna Korthals Altes), the personification of revolutionary France, who creeps through the galleries shouting “liberté, égalité, fraternité”. Her antagonist is Napoleon himself (Vincent Nemeth), who’s also in the museum, pirouetting through the palace’s vast halls shouting “c’est moi” and proudly lauding the connoisseurship of his artistic advisers. Revolutionary ideas of freely accessible art succumb to the greedy obsessions of an autocratic madman. How can enlightenment values of, say, free artistic education, survive if the artworks needed for that are acquired through plunder?

The relationship between art, ownership and power is also at the center of the second narrative, which is set during the German occupation of Paris. Not unlike Napoleon, the Nazis wanted to transfer the artistic treasures of their conquests to Germany. But by the time they reached Paris in June 1940, the paintings had already been safely hidden in various Chateaus. Sokurov focuses on the relationship between Franz von Wolff-Metternich (Benjamin Utzerath) who had the mission to bring the artworks “heim ins reich”, and the museum’s director Jacques Jaujard (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing) who initiated their relocation. Wolff-Metterich, however, deeply concerned about the survival of the works, pretended not to know anything about Jaujard’s activities, thus saving them from the risk of being destroyed by the war. It is historical irony that the two men would sacrifice their enmity for the survival of art, thereby reestablishing some of the enlightenment values Napoleon destroyed.

A final, more contemporary narrative shows Sokurov video-calling a captain storm struck on a cargo-ship, apparently freighting works of art across the ocean. Here again, the artworks are endangered by the political circumstances, this time of globalization. Is it really necessary to ship invaluable treasures of human history through storms to please the consumerist needs of tourists?

The question of the protection and property rights of art is certainly an important one, and has only recently become more relevant with the destruction of Palmyra by ISIS. The question also appears to have at least some importance for cinema, and with last year’s reintroduction of censorship laws, for Russian cinema in particular.

For all its homage to enlightenment, however, a rather naïve belief in creative independence runs through Sokurov’s film. At no point does it appear to occur to him that artworks may, at another point in history, have been complicit in the power struggles surrounding them. From the Assyrian statues to the Flemish portraits of noblemen that show up in the film, few, if any, of the artworks have been created in a context of political innocence. Yet Sokurov treats artworks like victims, and, in the rather turbulent political moments he decided to chose, increasingly as sacred martyrs completely removed from any kind of worldly associations. Beauty and goodness are one. Did it not appear to the director that this approach to art is at least as contradictory as the history of its ownership?

In the end Sokurov’s understanding of art is far removed from the democratic nostalgia of his Marianne. His fascination for the values of cultural heritage propagate a peculiar kind of elitism – the idea of the museum as the royal seat of the world’s great civilizations. Would Sokurov, for example, feel at home in Frederick Wiseman’s extremely worldly take on the British National Gallery? Instead of imagining a private Parthenon of timeless creativity, Wiseman’s museum is populated by personnel, interpretation, restoration, intrigue, budget cuts, in short, the stuff civilizations are made of.

Leave a Comment