Belorussian Private Shelter

Andrei Kutsila’s Guests (Hosci, 2015)

Vol. 64 (April 2016) by Patricia Bass

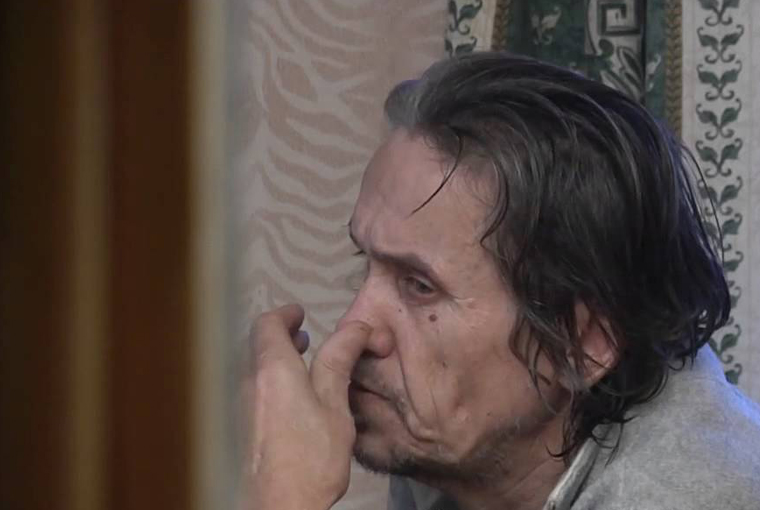

In a shabby but carefully furnished and tidied living room, Aliaksei sits next to an old woman, her body crippled by alcohol and years on the street. He begins taking her blood pressure. “I hope at least you won’t cry”, he chides.

“Are you crazy? I’ve cried enough,” she says.

“Yes, you’ve cried enough.”

Andrei Kutsila’s 2015 documentary The Guests follows Aliaksei, a 29-year-old man who has turned his own small house into an informal refuge for the poor, alcoholic, and homeless. Guided by faith and a particular obsession with Mother Theresa, Aliaksei cooks for them, monitors their blood pressure, and houses them in his Spartan living room lined with the cots they sleep on. His “guests” are seniors who he has “collected”, to use his terms, from the streets. When Aliaksei leaves the house for a Christmastime trip to Vatican City, he calls them frequently and sends postcards.

Aside from his guests, Aliaksei is shown interacting only once with a peer his age, another young man who helps him pack his robe for his trip to Vatican City. Aliaksei’s life is a far cry from those of other twenty- or thirtysomethings. His days are filled with prayer, house-making, and care for the elderly. His house is also populated with a handful of animals. He bemoans that “they” (municipal government? Legislation on homeless shelters?) won’t let him keep a pig, but he has other animals (a cat, a goat, chickens…) that he interacts with through the same matter-of-fact and sincere reproaches and observations he bestows on his human guests.

The film starkly lacks background music and narration, except in the closing scene, where Aliaksei walks down his country street to dour organ music. Most scenes feature interaction between Aliaksei and his guests, or the homeless that he tries to help in Vatican City, but many scenes merely depict the exterior of the house or the completion of household chores (fetching water, hanging up sheets to dry outside). Because of their enfeeblement, Aliaksei’s guests are incapable of much heated conversation, and they respond to their host’s reflections with simple assent, or observations (“There is no alcohol in this house”).

This austerity speaks to Aliaksei’s situation, and perhaps to Belorussian director Kutsila’s view of life in his country. Aliaksei is clearly in dire economic straits and depends on donations from his trips to Italy to pay his electricity and phone bills. Conversations reveal that his guests were forcibly taken to the hospital by ambulance during his absence, and that the authorities are not pleased that his home became “registered” as a legal homeless shelter or refuge (he uses the term “asylum”).

Kutsila’s films often return to the plight of the elderly and the obstacles to compassion under the post-Soviet regime of President Lushenko. His early works focus on an aging photographer (Focal Distance, 2008) and the musings of an older couple (Kill the Day, 2010). His more recent films focus on the trials of running a failing cultural center despite the culture of song present in Belorussian homes (Where you Belong, 2015) and the task of romantic relationships between those jailed for democratic organizing (Love in Belarus, 2014).

Kutsila’s concerns with the difficulty of providing aid in hostile conditions is clear. But his answers are not. Are Aliaksei’s guests truly provided sufficient medical care and attention? Are they happy? Is he happy? The film ends with typed credits which explain that Aliaksei’s shelter was eventually shut down but that during its three-year existence, it nonetheless housed over 100 people. There is no indication of what happened next, of what will happen now. But Guests nevertheless provides viewers, arguably the real guests, with a small, unstylized window into the lives of this host and his project.

Leave a Comment