Babushka Zina

Alexandar Mihalkovich’s My Granny from Mars (Moya Babushka S Marsa, 2018)

Vol. 89 (November 2018) by Colette de Castro

This Ukranian-Belarussian documentary, directed by Alexandar Mihalkovich and produced by Volia Chajkouskaya, takes place in 2018 Crimea. More than four years after Russia’s annexation of the peninsula, Mihalkovich presents us with a comfortless portrait of this coastal zone, which the Russians are no closer to getting out of than they were just after the so-called referendum. Putin’s recent Crimean bridge, which runs between Crimea and Russia, is another nail in the coffin. It creates a physical link to Russia, but distances Crimea from the rest of the European continent, where the family members of the film’s protagonist reside. Though it doesn’t feature in the documentary, the bridge’s presence looms large, as Mihalkovich captures shots of the seaside featuring Russian flags, hand-drawn portraits of Putin, and microphone-wielding karaoke singers praising Mother Russia in crooning voices.

Mihalkovich decided to give his documentary on Crimea a decidedly maternal slant – anchoring it in and around the universe of his grandmother, Zina. The director presents a tender and joking portrait of his grandmother. We see her bossily instructing her grandson about his trimming of the grape vine, but also watch her anxiously getting ready for her birthday, when she’ll go to a restaurant for the first time in over three decades. Zina is a jovial and youthful-seeming woman who lives in a small house near the seaside. For her 80th birthday, the family decided to reunite in Crimea to celebrate.

Traditionally it is children who tend to become inaccessible to their parents, but here the situation is reversed. The family is confused about Zina’s desire to stay put in a place where her outspoken political opinions get her in trouble with her neighbors. Zina had lived in different places in the Soviet Union. Once her husband died, she decided to move to the seaside to be closer to her sister who had also recently set up there. Together, they seem to have unwavering belief in the healing power of the sea. The most beautiful shots of the film are undoubtedly those of Zina breast stroking calmly across the unrippled surface of the sea in a bathing cap – a pink moon hanging just over her head in the twilight.

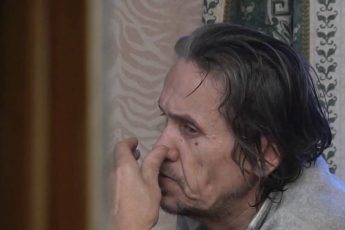

The theme of isolation pervades the film. When Mihalkovich’s uncle arrives for the reunion, he is panicking because he has no cell-phone coverage. Zina has isolated herself from her neighbors due to her political beliefs, and she represents a different generation than her family members and struggles to stay connected via the internet. There is an emotional disconnect between Zina and those around her too. When she talks about her fear of the planes she hears flying overhead, she sheds tears to memories of the Second World War. Today, she has a feeling that war is coming. Premonition of disaster is not unusual for old people, and these days it’s not unusual for just about anyone, but here it comes across as especially poignant because of her solitude and situation. Her ceiling is leaking, and the filmmaker captures her half-asleep and crying, crossing herself in silent prayer. But most of the time Zina puts on a brave face for the camera, and it’s obvious that while she remonstrates about her grandson’s way of life, lack of a good wife and a job, underneath, she is very proud of him.

Mihalkovich admits that for him, Crimea is a place of women. This is emphasized by voice and music. We see women dancing and singing throughout the piece. While male voices are mainly heard on television (say when we hear Putin giving a speech) or in the town-square; female voices are heard in the intimacy of the home. The speakers have a direct link with the camera. The three main protagonists, Zina, her sister and their Russian friend and neighbor each sing a song to the camera, each portraying a specific part of their culture. This brings to mind another Ukranian-Belorussian who has considered the importance of the female voice. In her 1985 book, The Unwomanly Face of War, Svetlana Alexievich unearths female stories of war though interviews with old women. “Their living voices will be preserved by the tape and the sheet of paper, and although these are not everlasting, they are still more durable than the best human memory.”

The family has gone to great lengths just to get to Babushka Zina for her birthday. The inaccessibility of Crimea for Zina’s family is shown to be doubly unjust because it is also a tourist mecca where visitors buy cheap trinkets by the dozens. In Europe, young people with money travel home several times a year to visit their families, in much the same way as they might have visited their families in a neighboring town fifty years ago. For Mihalkovich and his grandmother, the opposite is the case. For him, it’s as if his grandmother were living on Mars.

Leave a Comment