Brain Drains and Back Scratching

Cristian Mungiu’s Graduation (Bacalaureat, 2016)

Vol. 67 (September 2016) by Zoe Aiano

Roman Aldea (Adrian Titieni), a middle-aged doctor from the Transylvanian city of Cluj, sees no future in his country and has devoted his life to ensuring that his daughter Eliza (Maria Dragus) will emigrate. She’s done her part and earned herself a scholarship to Cambridge, and all she need do now is sail through her final exams, something she’s sure to do. That is, until she’s attacked and (debatably) raped in front of the school. Her concentration and academic dreams in tatters, her father takes it upon himself to ensure she gets the passing grade she needs, at the cost of his erstwhile moral high ground. What follows is a bitter critique of a society predicated on back-scratching, where the official channels are entirely ineffective and only the well-connected survive.

Yielding to the pleas of a policeman who owes a favor to a government official in need of medical care, Aldea becomes embroiled in a web of corruption in the hopes of pulling the right string to safeguard Eliza’s scholarship and thus her future in the glistening West. However, it proves impossible not to implicate Eliza herself in the murky dealings, further shattering already brittle relationships within the family. Cohabiting but emotionally estranged, Aldea and his depressed wife Magda (Lia Bugnar) take opposing moral stances, leaving their daughter trapped in the middle, forced to grapple with an ethical dilemma on top of the trauma of her assault and her doubts about leaving her home.

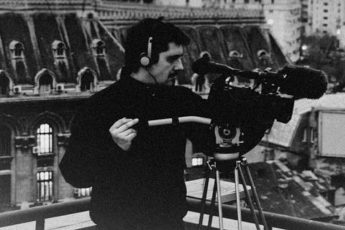

Once again, director Cristian Mungiu abandons the tripod for this film, alternating between anxiously hovering static shots and fly-on-the-wall style frantic chasing of the characters, making the presence of the camera ominously apparent. In slightly awkward juxtaposition to this agitated realism is a more intangible, Haneke-like expressiveness that manifests itself through a variety of unsolved riddles. The bristling tension begins with the opening scene, which sees a brick thrown through the family home by an unknown assailant for unexplained motives. Similar unaccountable moments of violence and suspicion recur throughout the course of the narrative, including a bizarre encounter with a child in a mask. Does Aldea’s have a hidden secret, in addition to the those we already know about, namely an affair with a much younger woman? Is the social fabric of modern day Cluj simply at breaking point, ready to erupt at any moment and in any form? As these questions are never answered, we are left to surmise that these interludes are a somewhat clumsy attempt at intellectualization that sometimes add to the atmosphere but more often distract from it.

While the decision to use rape as a plot point is, at best, brave, especially in a male-centered story, as in his previous 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, Mungiu’s critical assessment of the predicament of women within society and female agency is nuanced and thought-provoking. This is most evident in the case of Eliza, whose fate is shaped by a string of decisions made by men, from her assailant to the policeman who puts words into her mouth at the police station. Her father tries to take control of the language used to frame the event, repeatedly rejecting the term rape and insistently referring to it as an accident. He was also the one who made the decision for her to go to England in the first place, having invested heavily in language classes and extra tuition. She herself is hesitant about the move, and is reluctant to leave behind her sweet but unambitious boyfriend Marius (Rares Andrici). Despite at first appearing submissively accepting of these influencing forces, over the course of the film we come to realize that not only is she fully capable of thinking for herself, she habitually disregards the controlling advice doled out to her. As the catastrophe set in motion peaks, she proves to be the most judicious and reasonable of them all, yet tellingly deems it prudent to keep her decision-making to herself.

Graduation makes its point about the endemic corruption of Romania and its implications for future generations frankly and methodically. Perhaps the greatest flaw of the film is the extent to which this point is hammered home. The exchange of favors and underhand deals permeate every facet of existence. The police learn about deaths through a cousin who works as an undertaker and pays ambulance drivers for a tip-off. The construction site where the sexual assault takes place isn’t even a real construction site, it’s a tax dodge that has remained untouched for years. Magda’s apparently lowly status as a librarian is directly ascribed to her refusal to cheat at school. This may well be an accurate and damning reflection of the true state of affairs, but as a narrative device it eventually becomes wearying. Not only that, the unlikely coming together and falling apart of circumstances is not particularly convincing, which undermines something of the film’s realism. While the story is otherwise solid, worth watching and undoubtedly relevant, with a lighter touch it could have made its message much more devastatingly and been a truly great piece of cinema.

Leave a Comment