Politics, Gender Politics

Ewa Banaszkiewicz & Mateusz Dymek’s My Friend the Polish Girl (2018), Rustam Khamdamov’s The Bottomless Bag (2018)

Vol. 87 (September 2018) by Yoana Pavlova

If one thing has become apparent in the aftermath of the #MeToo movement, it is the fact that people from Eastern Europe were much better equipped for discussing gender equality in the years before 1989. After the troubling yet very creative atmosphere of the 1990s and the opulence of the 2000s, we now seem to be stuck in a never-ending decade marked by the financial crisis, social apathy, and the fusion of alt-right and neo-Christian discourses. In this climate, it is very difficult to objectively deconstruct the past with its stereotypes of and crimes against women. Take the recent public debates surrounding the ratification of the Istanbul Convention in countries from the ex-Socialist camp: under the pretense that the text “imported liberal values” from the West, the convention was met with anger and denial.

This conversation is even more difficult in the world of cinema, where the auteur theory (overwhelmingly centered around men) has been a substantial part of Eastern Europe’s trademark at international festivals. The post-#MeToo media avidly produced one think piece on Woody Allen after another, yet we saw very few takes on Roman Polanski. The truth is that after so many years ‘abroad’, he is still seen as a slightly improved version of homo sovieticus – someone who fell victim to the Western pop-culture’s allure (even if he largely contributed to its discourse), someone with less agency but with brooding, native talent. During his retrospective in November 2017, Cinémathèque française’s eschewal from debating critical views on Polanski’s figure and his work did not help much, unfortunately.

In this atmosphere of long-suppressed trauma, mutual accusations, and ongoing seismic activity in the cinephile canon and culture in general, it is up to curators and programmers to shape the conversation. At the opening of this year’s IFF Rotterdam edition,1 festival director Bero Beyer claimed that “we need to talk about sex,” then adding: “The last few months have revealed a pattern of widespread and often quite criminal sexual misconduct, committed almost exclusively by white, middle-aged, heterosexual men of power or status in the film industry.” IFFR’s sensitivity towards broad political issues has been part of its brand for very long, so Bero Beyer’s passionate stance was not a surprise. Moreover, the festival offered a platform for further exchange, including the Critics’ Choice IV talk around #MeToo and film criticism.2

Still, did IFFR practice what it preached in terms of programming? When it comes to gender politics, naturally, potential Oscar contenders such as I, Tonya (2017) or Phantom Thread (2017) were in the focus of attention. Nevertheless, two other, more subtle films from the New East – My Friend the Polish Girl by Ewa Banaszkiewicz & Mateusz Dymek and The Bottomless Bag by Rustam Khamdamov – formed an interesting diptych of sorts, introducing a new approach to la femme de l’Est and her habitual “mermaidization” in the Western gaze.3 Shown in the Bright Future and Deep Focus sections, respectively, both works skillfully played with over-aestheticization on the visual and mystification on the narrative level.

Ewa Banaszkiewicz and Mateusz Dymek have been collaborating for many years using various media, yet My Friend the Polish Girl is their first full-length title. Genre-wise, it would be most accurate to define this film as a ‘faux documentary’, as the term ‘mockumentary’ would automatically leave many aspects and meanings unexplored. Similarly to Mateusz Dymek’s student short Ewelina! from 2002, My Friend the Polish Girl follows the everyday life of a struggling actress (Aneta Piotrowska in the role of Alicja), only this time the setting is not Warsaw but London, and the camera is being held by American filmmaker Katie (played by actress and producer Emma Friedman-Cohen). Shot dominantly in black and white, except for a few episodes in color, what is particular about My Friend the Polish Girl is the fact that it borrows from web 2.0’s language, thus giving many scenes the feel of a vlog entry.

With the film premiering in Rotterdam, it was supposed to generate more attention and conversations, yet here comes the tricky part. Although Aneta Piotrowska has had a successful acting career in the real world, in Ewa Banaszkiewicz and Mateusz Dymek’s film she plays a depressed version of a Cameron Diaz-like persona who is subjected to gender and cultural clichés that could have been taken straight from a Ricky Gervais script. The impartial Western Kinoeye of Katie, the American documentarist who starts shooting a film on the sexy, sensitive, compassionate, and somehow confused Alicja, and the protagonist (qua not only Alicja but Polish women at large, as the title suggests) enter a perverse game of challenging each other, further succumbing to clichés as the notion of Brexit hangs above their heads like a dark cloud. The image of la femme de l’Est, looking for herself while also lending herself to others, has long been roaming the territory of arts and pop culture, yet to analyze its rendition in a project-provocation such as My Friend the Polish Girl takes some courage.

The problem here is not just gender stereotypes in Eastern Europe, but also the way in which Eastern European women are being pigeonholed into performing these stereotypes. In this sense, several questions arise. Does the film criticize the way Eastern women are being shaped by the Western gaze? Most certainly. Does the film claim that Eastern women own and wear these clichés as a leopard-print coat, which inevitably turns them into accomplices in the way they storify the clichés? Seems so. Does the very existence of the film as a work of art / social experiment pun these dynamics? Absolutely! In My Friend the Polish Girl, I personally see an amazing opportunity to discuss what #MeToo articulates on both sides of Europe, because this seems to be one of the toughest topics of today. My sole regret is that if such a debate occurred in Rotterdam, it probably stayed within the Q&A after the screenings, not really crossing festival borders.

Seemingly on the other end of the spectrum was a film that crossed borders for the first time – The Bottomless Bag came to IFFR highly recommended from Moscow International Film Festival, where it was awarded two prizes, the Silver Saint George and the Russian Film Critics Award. Rustam Khamdamov is a very particular artist within the framework of Soviet and now Russian cinema – with many opera and theater projects decorating his biography, he has a pronounced fetish for costume design, so whenever he resorts to film, it is being celebrated as a festive occasion. Some years ago, it was announced that Khamdamov will shoot a trilogy titled An Attempted Attack. His short Diamonds. Theft, the first part of this trilogy, was out in 2010. Now this first film seems more like a stylistic exercise for The Bottomless Bag, the second part, whose original title was Rubies. Murder, but at any rate it lays the foundation of a very particular kind of motif – women as a function of their attire.

In this context, it is noteworthy that The Bottomless Bag’s script is based on Ryūnosuke Akutagawa’s story In a Grove – the original material for Akira Kurosawa’s classic from 1950, Rashomon. Apart from the fact that Rashomon revolutionized cinematographic storytelling nearly seven decades ago, it is a case study juxtaposing the story of a widowed woman with the story of the famous villain who supposedly killed her husband. In the tradition of Russian humanism, Kurosawa (as a devoted follower of Dostoevsky) sees the female personage merely as a dramaturgical device, with the man standing as a generalization for humanity at large. This setting is slightly more elaborate in Khamdamov’s The Bottomless Bag, where the narrator is also a woman (80-year-old Svetlana Nemolyaeva), and a truly accomplished one. So if My Friend the Polish Girl features a female gaze directed at a woman’s body (hence the woman-eye and the woman-body are in a constant and ricocheting interaction), The Bottomless Bag introduces a strict hierarchy: a woman-storyteller reigning both in the court of Tsar Alexander II and within the fairy world of XIII-century Russia, in-house women (trophies or family) who happen to roam the splendid yet deserted palace of the Emperor, and a woman-story whose destiny and salvation are in the hands of the storyteller in charge.

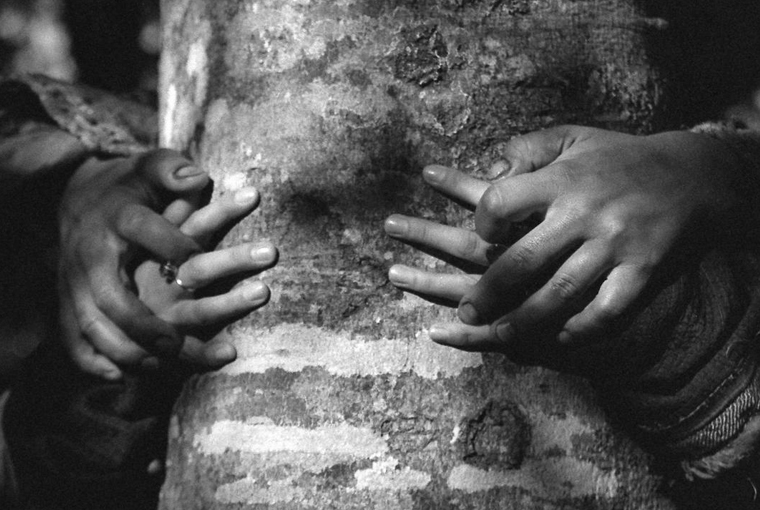

This intricate construction is being built with lightness and humor, even if the visuals, with their contrast and texture, are astounding, especially in the scenes featuring the forest and the water. The film plays with the classic codes of Russian cinema, folk tales, and visual arts with so much joy, that one can only imagine a self-confident and young mind behind it. As Iryna Marholina writes in her FIPRESCI report from Moscow: “Bottomless Bag is an example of ideational cinema given as enclosed system, which juggles with the senses in multiple ways.”4 There are Garbo references, mushroom people, mysterious black spheres, and a discreet conviction that beauty equals love. This ludic and romantic modus operandi turns Khamdamov’s work into a complex subject, mainly at times when we tend to politicize every gesture.

Thus, My Friend the Polish Girl and The Bottomless Bag, two films about women’s identity crises, be it within the social or the metaphysical order, that seem to have originated from the same discursive fields, came face to face in Rotterdam, on neutral festival ground. These are also two films deploying very different tools and modes, raising all sorts of questions about the position of women within and beyond the narrative, and most of all – about women who try to decode their own stories, to make and produce sense enclosed by the system of male-centered auteurism (albeit the fact that both works are ironically self-aware of that system’s post-existence). For a festival trying to show awareness of these stories and political meanings, IFFR could be a key meeting point for the East and the West to exchange on the matter, yet the West is apparently too busy dealing with its own #MeToo causal nexus, whereas the East generally lacks the vocabulary.

Leave a Comment