Representation and Meaning of the Dacha in Contemporary Russian films

Vol. 113 (March 2021) by Maxim Plokhikh

Despite its transition to a service economy and its heavy reliance on natural resources, modern-day Russia is still influenced by ways of life originating with the rural population and its centuries-long traditions. The social and political transformations of the 20th century have caused major ruptures in the standard of living of many Russians. The overthrow of Tsarism, the rise and fall of Communism, and the economic growth that has followed each of these ruptures, have led to the growth of urban populations and the gradual extinction of villages. Still, the rural reality has retained some of its grip on local culture. The phenomenon of the dacha occupies a special place within these transformations, as dachas are usually understood as houses where urban folks can spend time away from city life and out in the countryside.1 From an anthropological standpoint, the so-called “dachniki” are remarkable in that they carry over the peculiarities of dacha culture – chief among them the temporary change of patterns of behavior linked to urban life – into the present. The characteristic behavior of the dachniki chiefly relates to routine chores: planting seasonal agricultural products, repairing or rebuilding household items and the property itself, removing all kinds of garbage and waste, and so on.

Filmmakers recognizing the charm of and mystery behind dachas have tried to capture it in one way or another in Soviet and post-Soviet films. Both classics of the Soviet era and films of narrower outreach and ambition have been shot around the image of the dacha. This essay is an attempt to dissect the aims behind the representation of the dacha in contemporary Russian films. These films, which transmit the uniqueness of the dacha vibe, the unattractiveness of the dacha architecture, and the lifestyle of the dachniki, are a remarkable document for unveiling the hidden sides of this social space. They present the dacha as a place of detachment from the real world, a position which is aggravated both by the physical remoteness from the urban environment and the gradual decline of dacha buildings.

For the majority of Russians and many people living in other countries of the former Eastern Bloc, the dacha belongs to a separate world far removed from everyday city life, an attitude reflected in phrases used to describe the dacha such as “another plant”, “refuge” and “a piece of different life”.2 Throughout centuries of transformation, both the role and the perception of the dacha have undergone dramatic changes. In the period of tsarist Russia, dachas referred to small estates or buildings given to officials from the emperor (the word “dacha” is derived from “dat”, which means to give, and originally referred to gifts received from the emperor). Thus, until the 20th century, the dacha was not perceived as a product of an alienation from urban life – a sort of second-rate escapism -, but as a lavish country residence for nobles and distinguished servants of Tsarist Russia where they could enjoy balls and other sumptuous entertainments. This is reflected in the way these residences were furnished and arranged: they exhibited majestic facades and balconies and were equipped with additional floors. A remnant of this trend are the famous manor houses. The housekeeping, decoration, and “mission” of the pre-revolutionary dacha was captured in Nikita Mikhalkov’s 1977 An Unfinished Piece for Mechanical Piano (Neokonchennaya pyesa dlya mekhanicheskogo pianino), which was based on a Chekhov play. Filming was described in the following way:3

[…] the picture was shot in the town of Pushchino, an idyllic town on the bank of the Oka River at that time, where half a kilometer away from a beautiful and almost always empty hotel there was an abandoned estate with a two-storey stone house, a park of overgrown alleys and blooming ponds […]. Mikhalkov asked, so that each artist, regardless of the volume of his role, spent the entire filming period in Pushchino […] the whole way of existence (actors) was so unobtrusively, but precisely staged that the boundary between work and rest did not exist. And work was not a burden, and leisure time was naturally and unobtrusively filled with thoughts about work.

In other words, the role of the actors was to delve into the environment so as to adopt the norms of behavior of a long-gone epoch. Their frank nonchalance and ecstatic dialogues in luxurious outfits made them merge with their lavish environment. The location the film was shot on – an exquisitely constructed, wooden dacha – was a perfect match for this entourage.

What were the norms of behavior of that long-gone epoch? Mikhalkov demonstrates how the highest social stratum of the time transferred urban patterns of behavior into the dacha. The main characters of the film, whose action takes place at the landlord’s country dacha, occupy themselves with conversations about the difficulties of life to the sound of a piano. Their rhetoric and gestures are aristocratic through and through, conveying the impression that their urban norms of behavior remain unchanged despite the change of scenery.

Under the Soviet Union, a new era of the dacha environment began: local and state-wide party elites spent time in well-groomed dachas that were modelled on the vanishing aristocracy of Tsarist times, while ordinary citizens rushed to erect or rebuild their own dachas on a massive scale. Despite the fact that the dacha boom in the 1950s coincided with a rapid growth of urban centers, Soviet citizens liked the idea of living outside the city, on their own plot. Whereas spaces in dormitories, communes, or public dwelling spaces were scarce, the dacha became a summer outlet and a cozy corner for escaping ideological reality. Outside the crammed urban context, people had a place for “getting some rest”, which was especially beneficial for children.4 It is worth noting that the Soviet state not only created an artificial shortage of construction materials and dacha furniture (as is examined in Mikhail Voslenky’s monograph Nomenklatura). It also introduced restrictive building standards, according to which dachas could not be designed and built above two floors. Thus, dacha residents were enclosed in a strictly regimented environment in which established patterns of behavior and spaces of dependence were difficult to overcome.

The plot of a number of classic Soviet films was built around the dacha as a place of escape from the bustle of the city. The Oscar-winning 1979 feature Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (Moskva slezam ne verit) by Vladimir Menshov shows how a rural area is transformed by the arrival of dachniki.5 The term “dachnik” emerged at that very time. It refers to dacha residents – both permanent and temporary, though mostly the latter – and is often used with the connotation of a peculiar way of life that is established inside the own patch of ground.

Menshov follows the transformation process of the dacha over the course of several time periods. At the beginning of the story, the central house looks eclectic. It is assembled from building materials available at the time. Built from planks of different colors and shapes and hastily inserted windows and doors, the parts do not merge into a coherent whole. With no fence enclosing the territory and a lack of lawn care and laying paths, the space reflects the owners’ lack of care for bringing the dacha into a state that would generally be considered proper. During this time period, that is in the late Soviet period, the dacha arrangement grows ever closer to the aesthetic and moral customs of the Russian village.

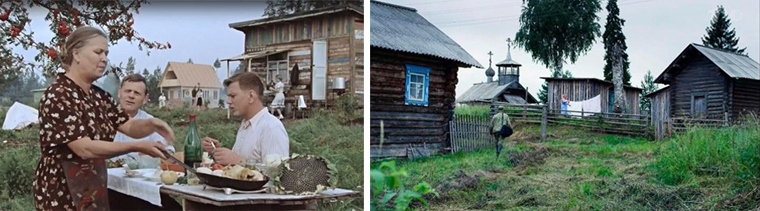

Today, in referring to the dacha, we usually have the Soviet artifact in mind – a status symbol of prosperous Soviet citizens who had an extra place at their disposal where they could rest. But post-Soviet films from Russia approach the dacha in a specific way not wholly continuous with their Soviet-era connotation. Thus, the collective and recreational character of country house stints has recently moved into the background. Instead, ideas of devastation and despair have haunted dacha residents onscreen, which are presented as effects of the space they inhabit. Notable films in this regard are Andrey Konchalovsky’s 2014 The Postman’s White Nights and Natasha Merkulova’s and Alexei Chupov’s 2018 The Man Who Surprised Everyone. In contrast to the Soviet approach to depicting the dacha, which focused on collective action and the involvement of dacha neighbors in their own lives, these films address issues of loneliness and people’s detachment from each other. The characters in post-Soviet dacha films are literally falling into the abyss of daily routine and the enveloping space of hopelessness. In both films, the dachniki inhabit a separate microcosm of the “little man” with a whole range of everyday challenges and social problems that intensify under the pressure of the dacha environment. This also translates into a different tonality: the motley composition of Soviet dachas is replaced by a dull, dark blue tonnage.

White Nights tells the story of a mailman in the Russian hinterland. Although the mailman is from the city, he chooses the path of dacha postman, transporting postage to a huge number of parcels day in, day out. Choosing a semidocumentary style of narration, Konchalovsky follows the mailman through a series of minimalist, stationary tableaux. The lowkey style underscores the letter carrier’s negligible importance and the senselessness of his existence. His existential crisis is aggravated by a theft of his property at the hands of dachniki, the departure of a fleeting love (who opts for life in the city), and depressing conversations about the hardships he is facing. The film dwells on the murky atmosphere that is conveyed through empty and dilapidated houses, sagging fences and unattended dacha plots. A sense of depression, melancholia and powerlessness seems to hang over the dachniki.

It is worth mentioning that this is not the first time Konchalovsky resorts to such a method of storytelling to follow the fate of ordinary people. Perhaps his favorite technique – the involvement of non-professional actors – can be retraced to one of his first films, The Story of Asya Klyachina. In The Postman’s White Nights, it translates into involving real dachniki in the making of the film. The director believed that no professional actor, however thorough his immersion in the local environment, would be able to convey the reality of the dacha periphery with all its subtle details, including people’s manner of speech and their peculiar behavior, which involves permanent moping and a lack of desire to pursue refined goals and needs. In the end, everything boils down to drinking alcohol and performing daily routines. The helplessness of Triapitsyn before societal progress and urban ways of life is encapsulated in the image of a space rocket launch at the end of the film.

A curious feature of Konchalovsky’s biography is his own relationship with the dacha. His memoirs reveal how he perceived the societal function of the dacha. He writes that “grandmother had a washbasin, an ordinary country house, with a metal rod, through which water was flowing – that’s all the achievements of civilization. […] Then the piano was no longer needed, he was taken to the dacha […]”.6 Here the idea emerges of the dacha as a space for using second-rate things that have lost their function in the city. Clothes that appear purposely outdated are perfectly suited for routine dacha duties, as is shown in Konchalovsky’s film. The memoir reflects on similar moments as well:7

[…] All alcohol should have been removed from the dacha, but it didn’t help either – it turned out that he was hiding the bottle in the doghouse […]. Mom came to the dacha in capron stockings, and grandmother was terribly outraged: What right do you have to wear capron stockings?! Where did you come to?! This is depravity! We live modestly! We are working people here.

These comic recollections reveal a whole lot about the gumption of the dachniki, who prefer drinking alcohol out on their dacha over getting drunk in the city, and who tend to dislike urban folks who do not adapt to the dachnik dress code when visiting their lots. (They also suggest that Konchalovsky’s perceptive portrayal of the sociology and atmosphere of the dacha environment is partially based on his own experiences.) The recollections fit well with Konchalovsky’s cinematic representation of the dacha environment: the dachiniki appear to be solely engaged in working or cleaning the dacha plot with occasional cigarette breaks, diluting the hardships of the working day with cheap alcoholic beverages. The real outlet from the everyday-life of such people is either a birthday party with a dacha neighbor, or the neighbor’s sudden death. Only these events can change the daily moods of people who have fallen into a real addiction to the dacha way of life.

In The Man Who Surprised Everyone, Chupov and Merkula present a similar view of the oppressive influence of the dacha upon man. Protagonist Egor (brilliantly played by E. Tsyganov) is a forester who protects wild animals from human inroads. But an unexpected illness makes Egor rethink the image and patterns of his own behavior.8 He changes beyond recognition. This transformation of Egor’s appearance causes an exceptionally negative response from the surrounding dachniki, who once used to approach the forester on good terms. The dacha’s vegetable garden, which used to be a place for growing vegetables, is now home to violent strife and malicious disputes. The patterns of aggressive behavior adopted by the dachniki are also causing real damage to the main character’s family, whose home is no longer a safe haven, but subject to repeated attacks and invasions.

Over the course of the film, the dacha space hangs like a cloud over Egor’s existence, so that he chooses to radically transform his own behavior. The challenges Egor faces culminate in extreme weather conditions, aggressive dacha neighbors, and the deadly disease that devours Egor from within. Breaking free from his oppressive routine, Egor goes into the woods and undergoes a kind of rehabilitation and recovery session, not only from his incurable disease, but also from the dacha lifestyle in general.

The time Egor spends away from the dacha is devoted to pondering existential questions about the meaning of life and his place in this world. The last scenes of the film are shot in a whitish gray, as Egor appears to the viewer like a supernatural martyr – in a clean, white robe, having passed the toughest tests, and having successfully completed the challenge posed by the dacha. It is safe to say that the former Egor no longer exists, and that he was figuratively murdered and buried on his own dacha plot. The new, reincarnated Egor, who overcame a deadly disease, will never return to his dacha plot again.

The directors thus capture an environment incapable of understanding or accepting other models of thinking. As the nonprofessional actors – again real-life dachniki -forcefully convey, different and alien phenomena are met with utter hostility and are never allowed to become part of the social environment. The stereotypization and stigmatization of external things and phenomena at the hands of dachniki, who inhabit architecturally primitive and generally speaking depressing constructions of mankind, hint at a close alignment of the dachniki with their permanent place of residence.

In contrast to Soviet-era connotations of the dacha, filmmakers’ focus has thus recently shifted to the personalities and inner conflicts of individual dachniki, whose lives are marked by existential questions, everyday challenges, and a harsh environment. The dacha here appears as another character of the film. It is not simply a scenery that sets the tone of despair and desolation, but an antagonist who actively opposes the mission of the protagonist to reach a better level of existence. This process of subjectifying the dacha in post-Soviet films allows us to see how the space directly affects people. It appears in the form of a trap – a trap that one can easily get caught in, but that is difficult to escape.

The films discussed above illustrate how the dacha suppresses people’s desires, leaving individuals struggling to satisfy their most basic needs. The surrounding environment does not allow you to develop your creative potential, because the performing of routine activities linked to life in the dacha environment condemns you to a vicious cycle of domestic dependencies.

References

- 1.Lovell, S. (2003). Summerfolk: A history of the dacha, 1710–2000. Cornell University Press, 8.

- 2.Lovell 2003, 3.

- 3.Adabashyan A. Plyus k tomu, o chem pishut drugie // Nikita Mihalkov: Sbornik. M.: Iskusstvo, 1989 (URL: https://chapaev.media/articles/4197) [Accessed on April 1st 2021].

- 4.Treivish, A. I. (2014). “Dacha studies’’ as the science on second homes in the West and in Russia. Regional Research of Russia, 4(3), 179-188; 187.

- 5.Caldwell, M. L. (2011). Dacha idylls: living organically in Russia’s countryside. Univ of California Press, 14.

- 6.Konchalovsky, A. (1998). Low truths. M.: Collection Top Secret, 9-11.

- 7.Konchalovsky, A. (1999). Exalts Fraud. M.: Collection Top Secret, 55, 9.

- 8.Animal destiny and nature are positioned towards civilization as the dacha environment was in Konchalovsky’s film: as opposite and incompatible components of one large whole. That Egor suffers from a fatal disease marks the poignancy of this conflict.

Leave a Comment