The Surface of a Yellow City

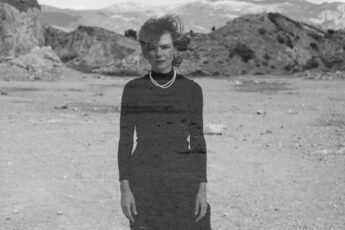

Siamak Etemadi’s Pari (2020)

Vol. 111 (January 2021) by Antonis Lagarias

In 2015, the world’s attention turned to Athens when the city became the stage of an international political conflict that revealed deep-seated contradictions inherent to the current make-up of the European Union. The existence of a common monetary zone and the delegation of financial control to European authorities forced Greek society into a never-ending circle of austerity. The results were not only growing unemployment and precarity, but also a change in the image of the country’s urban make-up. Athenian streets became the stage of ongoing clashes between political groups and the police, while financial districts were progressively abandoned as economic activity declined. At the same time, Athens became a destination for refugees and immigrants, which led both to a cultural revival of the city, and – coupled with austerity – to the emergence of a new-born fascist movement. A great number of contemporary Greek film productions use Athens as their background to evoke either the image of urban decay, frustration and poverty, or that of a place of transformational potential in the form of mass social movements.

A recent cinematic image of Athens draws heavily from these themes and comes from Iranian director Siamak Etemadi. The story of his debut feature Pari follows an Iranian couple, Pari and her husband, as they visit Athens to see their son Babak for the first time in two years, only to discover that he has abandoned his studies and disappeared. Since the local Iranian representatives don’t seem capable of helping, Pari convinces her husband that she will try and retrace the life her son had had for the past years in the hope of finding him. Her quest takes her to the anarchist scene, the recently developed immigrant’s district, Exarcheia – a neighborhood rife with politics -, and the prostitution areas around Piraeus’ port. Progressively, the film becomes less and less interested in Babak’s reasoning for abandoning his previous life and turns instead to a (Iranian) woman’s transformation inside an unknown community that seems mysterious and strange to her.

Pari’s relation to the city structures the reinvention of her identity. Starting from a stranger’s perspective, she has to find possible entry points to penetrate the surface of Athens since understanding the city equals understanding her son. Nightlife becomes such an entry point for Pari, who gazes at a city in ruins. The director avoids using all-too familiar Athenian imagery and instead guides the viewer through what seems to be a darker, underground side of the city. Artificial lighting is omnipresent, giving Athens a nightmarish yellow tint, while the interior is permanently contaminated by bright colorful neon lights that shine through the open windows of the city streets. This allows the film to partially avoid a straightforward stereotypical depiction of East/West dynamics since Athens is nowhere near to being a dream-world of Western civic freedom. The city gains a symbolic function, representing an ambiance of chaos, decay and decadence, all of which are implied to be necessary ingredients for personal transformation.

The theme of a woman’s emancipation has been studied extensively in films, to the extent that its employment today can only be put in relation to existing themes. Escape from male control (e.g. from a father or husband), financial independence, religious defiance, self-education and knowledge, are all well-known steps in remarriage stories and melodramas. To these we may add sexual exploration, acceptance of Otherness, and political activism. The film seems to fall victim to being too self–conscious about the existence of these themes. By trying to tick off most of them, it fails to invest either time or creative energy in an in-depth analysis of either of them. Thus, Pari’s path to rejecting her current life seems full of useful random events that are partially addressed as conceptual arguments to the viewer. Sexuality between women is expressed through a random kiss with a girl that does not alter Pari in any meaningful way; resistance against male aggression is represented by an encounter with an unknown rapist allowing Pari to show a fighting spirit. Similarly, political consciousness is introduced in Pari’s passage through the Athenian anarchist community, which is so brief that it results in reducing the community to abstract violence and clichés about “troubled young souls”, which simplifies the complexities of political struggles. Certainly, the unexpected death of Pari’s husband is the best example of how the need to serve an argument is forced into the film’s narrative.

While the director’s intention is to map a woman’s journey towards answering her dormant desires, the lack of an in-depth deconstruction of any of these steps inevitably leads to an equally forced ending. Pari chooses to abandon her life and disappears just like her son after having lost her husband and child, both of whom are now absent due to events out of her control. Since she no longer has social duties to fulfill, her decision to abandon her previous life becomes less radical. The film ends up telling the story of a woman who is enabled to reject her existing life – or rediscover who she is – due to purely external causes.

While perhaps equally powerful on an emotional level, this approach brings an unsatisfactory political aftertaste. Does Pari fall victim to this strange new world that consumed both her husband and her child? Did her journey activate her dormant desires of freedom, undefined as they previously were? Is Babak’s path a reflection of her own true path, accessible to her only indirectly by delegation to her offspring? This overlap of different questions creates a narrative ambiguity, preventing the film from assuming a clear emancipatory structure that would let Pari master her own destiny. The strong aspect of the film is its depiction of Athens’ vibrant urban space, which provides an intriguing playfield for exploring one’s identity. However, at a time when a female gaze is struggling to establish its rightful place in cinema, the film’s narrative weakness with regard to its emancipatory theme remains quite striking.

Leave a Comment