The magic of Atom Egoyan’s Calendar is that for all the complexity in which the movie’s themes are interwoven and connected, the film’s narrative development remains remarkably straightforward and simple. Second-generation Armenian Canadians, a photographer (Egoyan himself) – whom I will simply to refer to as “Photographer” for lack of a name (similarly with the driver and translator) – and his wife (played by Egoyan’s real wife Arsinée Khanjian), who serves as his translator, travel to Armenia to take pictures of ancient monasteries and churches for a glossy calendar series. They are accompanied by an Armenian Driver (Ashot Adamyan) who imposes himself as their unofficial tour guide. While the Photographer’s wife increasingly connects with the Armenian landscape, history, culture, and, ultimately, the Driver with whom she falls in love, the Photographer isolates himself behind the camera and is unable to establish any personal connection with the topic of his photographic series beyond the technicalities required by his art. This quasi-autistic behavior alienates him from his surroundings and most dramatically from his wife. Back at home after the shooting, he spends months in the editing room replaying the footage in an attempt to spot the exact moment that destroyed their marriage, something which escaped his observation on site.

At first sight, Egoyan’s film simply appears to tell the story of a romantic love triangle, where the documentary footage of the Photographer’s journey comes to represent evidence of his marital failure. In these scenes, we see his wife interrogating him behind the camera, asking questions like whether their journey means anything to him, whether the historical information provided by the Driver in any way changes the way he sees the objects of his pictures, and finally, whether he would like to go for a walk to see the surrounding countryside. In the beginning, the Photographer minimally interacts by asking questions of his own, but soon fends off his wife’s conversation by asking her what she means, claiming that he doesn’t understand her questions and that he prefers to stick with the camera instead of going for a walk. As his wife’s relationship with the Driver gets more and more intimate, many of the Photographer’s comments have an air of jealousy, especially when he asks whether the Driver could possibly expect more money for his explanations or when he, somewhat contemptuously, replies “I guess” to practically all of her questions.

On another level, these scenes have been interpreted as the Photographer’s failure to identify with his national roots.1 True, he takes pictures of some of Armenia’s oldest national symbols shortly after the Soviet Union collapsed and Armenia gained independence. During Soviet times, such national reminiscence was, of course, undesirable. The workers of the world were supposed to disconnect from their traditions, especially religious ones, which threatened the uniformity of the utopian project. After the fall of communism, Armenian Churches and Monasteries were quickly revived as symbols of a collective identity.2

The Photographer’s own yearning to belong to this community, however, is much less obvious. The photographic series is a commissioned assignment, so there does not seem to have been any personal motivation for the Photographer behind going to Armenia. The finished calendar on the walls of his apartment in Canada is hardly evidence enough for speculating about his nostalgia and/or troubled identity. Clearly, he doesn’t identify with anything Armenian, be it the language, the culture or its history. Also, he doesn’t seem to actively try to substitute this lack of identity with some imaginary culture, like the one depicted by the calendar. Nor does he seem to justify his lack of identification by irrationally relying on, say, his Canadianism.

If anything, such identity trouble is best portrayed in the character of the Photographer’s wife and the Driver. The Driver’s connection to the monasteries remains largely symbolic and performative. His encyclopedic knowledge can hardly resuscitate a living religious culture so that, ironically, the monasteries remain as dead for him as for the Canadian Photographer. He even comes to this conclusion himself, remarking that he knows so much about these places without really knowing anything about them at all, this lack of knowledge perhaps representing an inability to experience the religious edifices in the same way as the community for which they were made.

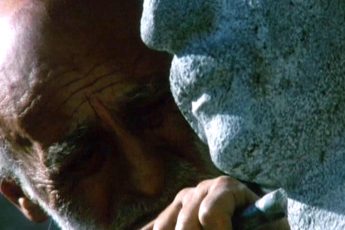

Diasporic communities often tend to compensate the fact that they don’t fully identify with their host culture with symbolic elements that remind them of what they consider their home. With two-thirds of Armenians living outside the country, the collective identity of Armenians has long been defined through the church and their language more than through the borders of their country. The personal meaning the Photographer’s wife attaches to the monuments can easily be seen as a way for her to fortify her own Armenian identity, which may also be the reason why she is attracted to the Driver. Both the Photographer’s wife and the Driver treat the monuments as if they were somehow part of their own body and soul. They believe that they can “touch” and “feel” the monuments and that they disclose a special “meaning” which is reserved only for them. Symbolic for the Photographer’s failure to produce a similar attitude is the fact that he is visually absent from his own documentary footage. While the two other characters constantly interact with the monuments, the Photographer hides behind his camera. His refusal to enter his own frame in the scene where his wife asks him to take a walk could be interpreted as an unwillingness to establish any emotional or physical connection with the monuments or with whatever else they represent to his wife and the Driver.

Nevertheless, it would be mistaken to claim that the Photographer actually ever wanted to establish such a connection, or that he would be less alienated if his relationship to Armenian culture would somehow be more harmonious. The truth is that the Photographer’s alienated personality does not really seem to have anything to do with his personal attitude towards Armenia, but with something that could best be described as existential emptiness. Thus the Photographer’s real problem is not that he cannot connect to the Armenian monasteries, his past, or some imagined community, but that he is unable to establish a human relationship with anything at all, be it his wife, his job, or even himself. This is especially apparent in his inability to communicate. Most tellingly, he never directly communicates with his wife nor she with him. Virtually all of their conversations pass through some technological device. In Armenia they communicate through his camera, back in Canada, they communicate through the Photographer’s answering machine. Accurately, NY Times critic Stephen Holden wrote in his review that the film could have been called “Sex, Lies, Videotape, Film, Telephone and Answering Machine.”3 And, with Hamid Naficy, one may add letters to this list, as the Photographer also tries to communicate with his wife, though he doesn’t produce anything beyond drafts.

More than identity politics, Calendar thus seems to address classical issues of existentialist thought about the alienating power of technology. Indeed, the Photographer seems to be trapped in a materialist or capitalist worldview in which human relationships are instrumentalized. It may be no coincidence that neither the Translator nor the Driver have a name in the movie and that both of them repeatedly feel that they are being used. The Photographer’s idea that the Driver wants money for his explanations should be taken literally: even cultural exchange has monetary implications. The key question of the Photographer’s wife is when she tells her husband that “it’s practical right?”, referring to her translations and to herself as having been reduced to an inanimate tool. It is ironic that the churches are reduced to the very same productive utilities, since mystical and religious experiences are often considered to provide a setting in which alienation can be overcome. Mystical experiences may help one to see oneself as a more finite, conscious, and responsible human being.4

The real reason why the Translator connects to the Driver may not be because he somehow fulfills her desire to reconnect with her roots, but because the Driver, unlike the Photographer, actually sees her the way she is. She even tells her husband that her strongest memory has nothing to do with the churches but with a flock of sheep that prompted the Driver to touch her hand. Perhaps she is thus yearning for human contact more than for the alleged values of belonging to some abstract community (as is the claim of the identity analysts).

The only direct conversations the Photographer has, are with a dozen foreign girls he meets for dinner through an escort service, another, rather extreme instance of instrumentalization. In a series of dinner scenes, each girl asks to use the telephone, presumably calling some foreign lovers (the conversations are not subtitled), their voice suddenly turning affectionate, sometimes even passionate. Certainly, this could mean that one can only be truly affectionate in one’s mother tongue, which would hence run home another variation on the theme of identity. But regarding the stiff silence reigning over dinner, the phone calls look more like flights from the Photographer’s dispassionate slant towards whatever little the girls have to say.

Although the Photographer’s wife appears emotionally less detached, it should not pass unnoticed that the she is as alienated from the world as her husband. In fact, her translations are as mechanical and meaningless as her husband’s photographs. As the translator Nairi Hakhverdi has noticed in an excellent article for Asymptote, many of the Driver’s extensive historical descriptions are reduced to their bare minimum in translation – conversations between him and the Translator remain entirely untranslated.5 But what is left in translation is monotonous in tone and meaningless in content. Again, it appears doubtful that this is a problem inherent to communicating in different languages or of not being able to identify with the linguistic particularities of another culture. It seems much more likely that the inability of the characters to communicate meaningfully is the result and not the cause of their alienation. One could go so far as to say that if the Photographer were able to think about his identity, he would probably be less alienated, self-understanding being an important progress towards a less alienated life. But as it is, he does not seem to have realized that he has an identity at all.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, all of the characters in the film seem to be either unaware or disaffected by the fact that they are in country that is in the middle of a war. To go on a photographic journey for a kitschy calendar series while, a few hundred kilometers southeast, similar monasteries are being destroyed in blood-battle, is at best utterly naive and at worst cynical. In this regard, it is awkward that commentators insisting on the theme of identity politics did not find the film’s silence on the Nagorno-Karabakh War in any way disturbing. For anyone identifying or wanting to identify with Armenia in 1993 would surely be affected by these interethnic conflicts and certainly also by the intra-Armenian discords, particularly those surrounding the political goals of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation that also heavily acted on the diasporic community. Of course, true nostalgia is romantic, so taking pictures of a country in ruins would perhaps contradict the initial purpose of the journey, which is to find a home unbroken. But the Photographer is no such romantic. He simply has a job to do. The absence of any imminent historical reality in the film thus matches the general theme of alienation and the characters’ inability to relate to their surroundings.

Alienation may be too boring, old-fashioned, and far too less exotic of a theme too have sparked much commentary on a film whose larger part takes place in post-communist Armenia. But in reality, Calendar is as much about the complexity of the Armenian identity of the diaspora as Lars van Trier’s Melancholia (2013) is about planetary collision or Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man (2005) is about bears. Calendar is, perhaps along with Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation (2003), one of the most remarkable films about how existential loneliness passes communication (the cause of alienation in Coppola’s film, by the way, is also hardly provided by the characters’ different cultural identities). Only at one point, while reviewing the footage of a ruined church at home, does the Photographer personally relate to his journey, realizing that his alienated personality might have been the cause for the break-up with his wife. Rather poetically he says: “All that’s meant to protect us is bound to fall apart, bound to become contrived, useless and absurd. All that’s meant to protect is bound to isolate and all that’s meant to isolate is bound to hurt.” Suddenly, in the aftermath of events, after the calendar and the Photographer’s own identity have passed by, his relationship with his wife come to signify their true meaning: solitude, sadness, injury.

Excellent analysis and critic of this movie ! My dad just showed me the “Calendar” and firstly, I did not really understood the meaning of the story and the message that Egoyan wanted to share. Only one thing remain unclear for me, why every time the photographer pours some wine into the ladies glasses, they automatically ask for the phone ? Thank you very much for this explanation !

Huge thanks from France, sorry for my English mistakes ; )

Solal AURIOL.