Welcome to the East?

Chantal Akerman’s From the East (D’Est, 1993)

Vol. 15 (March 2012) by Konstanty Kuzma

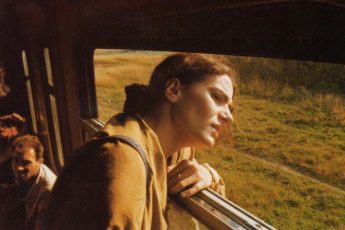

Shortly after the iron curtain fell and the Eastern Bloc started falling apart, Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman traveled to Moscow by train to capture a crumbling world “before it is too late.” How soon it would have been too late to witness the remains of this world is hard to say, but from Akerman’s journey resulted From the East, a static 110-minute documentary released in 1993, mainly consisting of tracking shots of waiting crowds boldly reciprocating the camera’s gaze. The concept of From the East is similar to that of Tokyo Ga, where German director Wim Wenders travels to a similarly alien world: Tokyo. The Japanese capital is frantic: Wenders observes Pachinko parlors, funky Japanese TV shows, over-crowded trains, and in contrast to all this, Yasujiro Ozu – a fixed point amidst the ever flashing city lights. The purpose of Wenders’ journey to Japan is his fascination with Ozu’s work, which brings the film a loose narrative mediated through the ingenious voice-over. But where Wenders is lyrical and essayistic, Akerman sends us post-cards from a bleak world. “Drama is life with the dull bits cut out,” Hitchcock once told Robert Robinson in an interview for the BBC (05th of June 1960), and to Hitchcock’s credit, From the East is excessively boring…

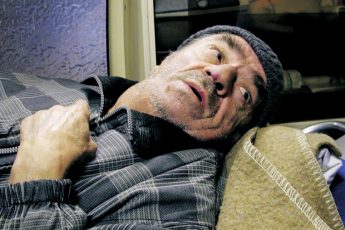

The film sets out in Poland, with a few sprayed cement blocks and a wall that is barely tall enough to serve as an analogy to “the Wall”. There is a Warsteiner beer sign, a man who’s waiting for the bus, smoking and drinking beer, and trees that blow in the wind. We wouldn’t be able to tell the place or time of the setting hadn’t it been for the title screen: Akerman wanders around an anonymous world, one that lacks identity as much as any village does. Only as we travel further eastwards, the East seems to reveal its ‘real’ face with the eternally sad landscapes and grey skies, a place where people seem to live troubled and monotonous lives. Often, the camera will track alongside large groups of people waiting at a train station or bus stop: some glance at the camera, some stare at it, others ignore it; some are silent, some smile, some seem displeased. Meanwhile, the noses and eye-brows ascend and descend in height and position, warts and pimples appear from time to time, and make-up partly conceals the pale skin tone of women. Grim faces, grey walls, muddy landscapes: indeed, Akerman is not particularly worried about picturing the East in a favorable fashion. The fact that these masses of people do not seem to mind the eternal and purposeless waiting is troubling, if not disturbing. But then again, waiting was not an activity foreign to the citizens of the Eastern Bloc. The lines you had to endure in the Soviet Union (as well as many Socialist countries) only to obtain basic products such as =toilet paper were notorious. There is a joke from Glasnost times in which a man, standing in such a line, suddenly snaps, leaving the line with the intention of assassinating Gorbatschow, thus hoping to avenge the unchanged economic misery. Soon enough, he is spotted rejoining the line, as it turns out that the line for killing Gorbatschow is even longer than the one he had been standing in…

Looking at Akerman’s oeuvre, though, it is doubtful that the East alone is to be blamed for the aggressive monotony in From the East (indeed, one may conjecture that a film of Akerman about Japan would not have been shot in Pachinko parlors either). Rather, throughout her work, Akerman is constantly challenging a certain conception of art: her work is not simply Anti-Hollywoodian, but opposing the superficial connection of cinema with drama. The tension here is not between real and false emotions; the problem lies precisely in the ominously transparent organization of emotions on screen. Everything is too obvious, too simple to be true, ready for consumption. And of course, there is another enemy: time, or, rather, its non-existence in a cinema that paces and shouts and shoots, but becomes perpetual in Akerman’s films. From the East, be it intentionally or not, convincingly embeds these struggles into non-fiction, in this case a world where stillness reigns over words, and nobody seems to worry about the purpose or meaning of it all. It all just sits and stands there, unconcerned about what we, the observers, may think – the boldness of existence, a power one is glad to be reminded of. Certainly, Akerman’s films thus challenge the boundaries of the cinematic medium, though the risk with such a radical approach is that it may fall wayside. If in one way or another, art is always a juvenile compromise between wanting and wanting to want, the real extent of this struggle is seldom uncovered as thoroughly as it is in a film like From the East. For those who hoped for an earlier ‘climax’ in Jeane Dielman, this film will be a tough bone to chew on. But perhaps, it is a torture worth going through. Wait and see.

Leave a Comment