In Sweet Movie (1974), Serbian director Dušan Makavejev returns to his grand theme sexuality following the success of his 1971 feature W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism, an hommage to Austrian psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich. Sweet Movie, though often sidetracked by minor subplots, centers around a young woman who gets married to a US millionaire. The film opens with an American TV show on which the mother of the tycoon intends to find a suitable bride for her son. The contestants for the Miss World beauty contest enter the stage and, once there, sit on an elevated chair where they are given a “close” examination (Makavejev does not miss the opportunity to exploit this pun) by the present doctor who is to determine their eligibility. The undisputed decision is Miss Canada, our protagonist, and soon enough we are at the wedding where the millionaire starts explaining why he decided to marry, instantly revealing his real self (“Marriage is a great way to save money, and time, which is money!”). Intercut with this story is the romantic tale of two impoverished “comrades” who find love on a boat ostentatiously decorated with a huge Marx bust. After a quick ideologico-sexual dialogue, the two strangers start doing it on the boat, unbothered by the crowd watching from the shore. Meanwhile, Miss Canada struggles to find love as the marriage with the horrid millionaire draws to an end. She falls in love with an actor who she has sex with on the street, but their affair, too, turns out unlucky as the two get caught in a “love cramp”, being unable to end their act…

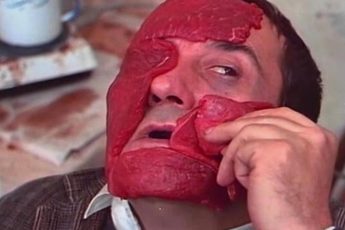

Though Makavejev is known for despising linear story telling, Sweet Movie is exceptional in its purposeless roaming. Characteristic of the film is a mass dinner scene accompanied by ceaseless collective vomiting. Unable to rely on a proper story or message (most of the film’s dialogues are self-ironic or ridiculously exaggerated), Makavejev seems to be dependent on celebrating such shocking scenes. The film quickly drifts into affluence and aimlessness, words that also describe the bourgeoisie which Makavejev is so keen on ridiculing. Ironically, Makavejev’s critique becomes completely reversable: just as the extravagant life style of the upper class demands ever greater escapades to satisfy the curiosity of the rich and the beautiful, so Makavejev is forced to shock with ever greater provocations – sexual and violent – to keep his audience interested. However, it’s usually a poor idea to fight boredom with repetition. Soon one grows indifferent towards Makavejev’s piece, nevermind the chocolate girls and golden phalluses. The film thus highlights the weak points of Balkan cinema, where it is often but a crumbling facade of meaningless sex and violence that covers up the blatant lack of meaning.

Leave a Comment