Věra Chytilová refused the label of feminist. For someone as rebellious and free-spirited as she was, it is conceivable that any label could be felt as constrictive and therefore unacceptable. It is also possible to put this reticence in context, for example Carmen Gray attributes it to the geographical/historical moment, “in a central Europe in which the activism of feminism tended to be ridiculed or belittled and viewed as a posturing western import”1. Yet, even if the person was allergic to the label, her work is often associated with feminist themes and thinking. In this essay I will focus on the filmmaker’s perhaps most known work, Daisies (1966), to explore how it carries feminist values.

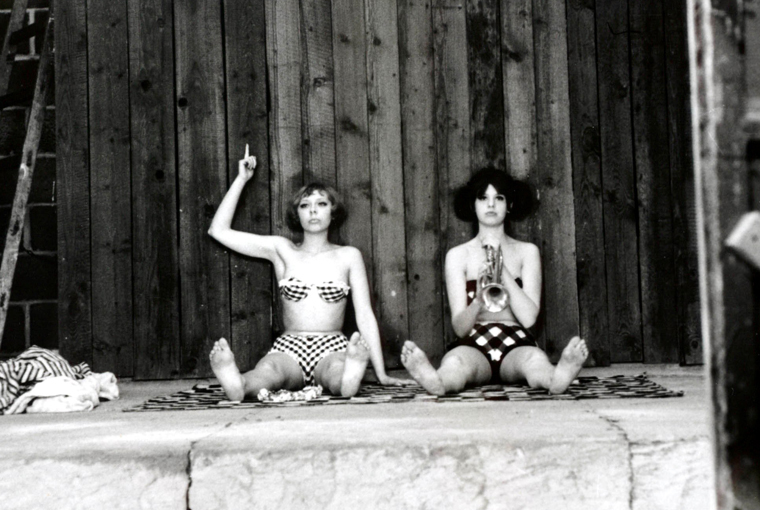

The daisies are two very young women, played by non-professionals Jitka Cerhová and Ivana Karbanová. The two women have no history. The viewers are not informed of anything about their past or present lives, no background is given, and no foreground either. They seem to have no goals, to want nothing material or emotional and to gleefully move nowhere. They don’t even have a name, so they are both referred to as “Marie”.

What they do have, is each other. They matter because they are (young) women of no consequence. Their significance as persons, and as characters, is not attached to their history or their role in society. In fact, they carry no value in a culture of productivity, they have no place at the table of society, they are entitled to nothing. Yet, this film is them, only them and completely them, they conquer every frame and every minute with the sheer force of being two women who are alive.

This film is not only populated almost exclusively by (two) women, but it is physically filled with them. The Maries are not only in every shot where there are humans, but the shots are often narrowly cut around them, leaving no room for others, as if nothing else mattered, or even existed. The question of what matters is also a leitmotiv of their dialog where one asks ‘Does it matter?’ and the other invariably responds ‘It doesn’t matter’. What seems to matter is their constant and enormous presence. Such presence, so intimately followed by the filmmakers, is already, in an immediate way, an act of feminism in a world where women were supposed to be secondary when not silent and invisible.

In addition to this representational level, the intimacy of the shots and the fabulous complicity of the Maries, add a powerful affective dimension of love for women, which I don’t hesitate to call feminist. It is very rare in the history of cinema to encounter two women with such deep bonding. It is even rarer to see on screen a similar connection based on the quest for joy and play.

The pleasure that they experience when fooling around together, which is what they do all the time, is palpable and exhilarating. They are capable of generating infinite amounts of giggling and laughter just by being together and the immediacy of their mutual understanding is fantastic.

In their very first scene Marie declares that ‘Everything’s going bad in this world’. Then, going back and forth, they finish the sentence by deciding that ‘If everything’s going bad…’ ‘so…’ ‘we’re going…’ ‘bad…’ ‘as…’ ‘well’.

In the bedroom the Maries share, they practice their going bad. They are found in this location at various stages in the film, often in their underwear or petticoats, very often lying down, jumping around or walking over the large bed. In one sequence they set fire to stripes of colored paper hung from a wire structure above them and proceed to cutting them to pieces and eating, while sprawled on the bed, phallic foods: sausages, gherkins, bananas. Throughout the bed food orgy, one of the Maries’ lovers (whose name she doesn’t know), goes on and on declaring his love for her over the phone, while the women pay him no attention, as if his voice was just background noise.

In a later moment, playing again with fire, a bathtub has appeared in the room, heated by a small bonfire underneath it. The Maries fill it with milk, and drop in salt, an egg and the cut out of a photo of a male body builder, which they push down to invisibility. Then they both jump in, naked, while wondering about their own existence. Marie asks Marie ‘How do you know it’s us? How do you know you exist?’, while the other Marie responds ‘Because of you!’. To which Marie retorts that of course that is the case, since her friend is not registered and doesn’t work, therefore not existing. Red-haired Marie is not recognized as a person because her name is not on any official papers or contract. She is not a worker, she is not a lodger or an owner (and she’s not a wife, mother or daughter, one might add): she doesn’t exist. Except, she is dark-haired Marie’s friend, kin and playmate: she exists because of her relationship with another woman, the type of relationship where the two can be naked together and perfectly happy just frolicking in a bathtub. Nothing matters but their playing together.

But asserting existence can be elusive and a few minutes later they are confronted with a gardener and a group of cyclists, all men, who pass by them as if they were see-through. This time their bodies, instead of their social identity, are plunged into invisibility. It is then something material, rather than their affective bond, that can prove their existence: looking around in wonderment and disappointment, they notice the trail of corn cobs leaves they left behind. The waste tracing their passage proves that they have been, and still are, in fact, there. This reassures them, and they improvise a cheerful chant “We exist, we exist, we exist…” while marching together. Again, the two women are enclosed in a tight two-shot, their swinging arms almost touching the edges of the frame to the right and left, their heads and feet brushing the top and bottom. The camera transforms the public open space into the world when they can make each other be. To the men around them they are invisible, but in their togetherness and mutual recognition they exist. When they transform the spaces they occupy – their room, the bathtub, the frame itself – into a complicit playground, they matter to each other and therefore they exist.

The sheer fact that all they invest their energies in is having fun and each other’s company, is in itself a feminist affirmation, if anything because it goes against the grain of the patriarchal conviction that women are either dependent, complementary or subordinate to men. This plane of direct critique of wide-spread everyday misogyny, often takes the form of mockery in Daisies. Marie and Marie repeatedly toy with the conventional dynamics of man-woman relations.

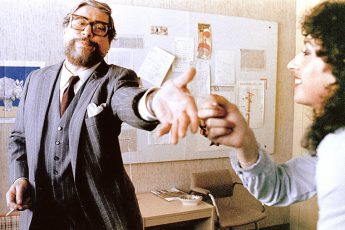

The Maries’ dining with an older man is presented in several iterations. The man is always a different one. In an early scene, he is placed in an upmarket restaurant with dark-haired Marie. Soon red-haired Marie joins them posing as her friend’s sister. Uninvited, she sits down and orders huge amounts of food, which she eats ravenously, often with her hands. During the first sequence of this sort, after she is barely done stuffing her face with pastries covered in whipped cream and has noisily sipped a bowl of soup, she is served a whole roasted chicken, which she immediately punches down with her fist (a moment as hilarious as it is powerful) before pulling away the animal’s leg to devour it. She also manages to gurgle down glasses of wine and interrogates the man about his children and age.

From the arrival of the chicken on the table, Marie’s ingurgitating frenzy is punctuated by in-camera colored filters and edited with rhythmic jump cuts for the rest of the awkward lunch. The black and white image is tinted violet, then orange, then green, B/W, orange, B/W, green and so on.

The Maries play this prank on various men. Every time they go to the train station with them after the meal and have the man believe that Marie is going to leave with him. While the other woman performs the pathetic gesture of waiving a handkerchief, Marie gets on the train with the hopeful man, only to jump off from the back door as soon as the train starts rolling away, rejoining her friend on the platform in a cloud of giggles.

Destruction is very present in the action and in the form: the Maries destroy vast amounts of food, set fire to their own room, cut themselves into pieces. The editing can be said to frequently destroy continuity: black and white images alternate with color images and in-camera color filters randomly, sound is often incongruous and abrupt, and archival images of war bombings are scattered throughout. Linearity is constantly and intentionally shattered. Chytilová herself2 recognizes that destruction, both material and moral, is a dominant theme, but her elaborations on the forms and meanings of destruction are far from univocal. She thinks of destruction as brutal, liberating, rebellious and as a creative force. At times as a necessary road to asserting existence.

Tout ceci vaut dans la mesure où il existe une possibilité d’expliquer la destruction comme activité creatrice. Même si le processus est purement négatif, il trahit, en un sens, un besoin positif, le besoin, très normal, de marquer son passage, de laisser des traces de son existence.

This side of destruction as being conducive to creation and to novelty recalls closely a concept of feminist cinema elaborated by Teresa De Lauretis in 1987, in her essay ‘Rethinking Women’s Cinema: Aesthetics and Feminist Theory’, when she proposes that

women’s cinema has undertaken a redefinition of both private and public space that may well answer the call for “a new language of desire” and actually have met the demand for the “destruction of visual pleasure”.3

Formal manipulation by destruction, De Lauretis proposes to call a ‘feminist deaesthetic’.4

Daisies’ deaesthetics, an exhilarating toying with images and sound, is intrinsically connected with a disassembling of moral norms, what Parvulescu calls an ‘assault on manners’5. The form is explicitly, even aggressively, protean while its ethical projections are ungraspable but permeated with life and the pleasure of de-making the territory. What is unique in this film, is that its aggressive social and moral critique that is interweaved with its explosive deaesthetics, is not imbued with negativity. Quite the contrary, it is alive with joy. Steven Shaviro, on his blog “The Pinocchio Theory”, recognizes that Daisies, while performing a “violently nihilistic assault”, is far from negative. Rather, he describes it as “a joyous plenitude, an overabundance that is both affective and material, embodied in the sheer exuberance and formal inventiveness of the film itself.”6 Daisies invents an almost impossible cinema mingling material deaesthetics with – echoing De Lauretis’ neologism – brutal de-ethics, and it sustains this daring operation with powerful joyfulness.

The unconfined joy makes the destruction affirmative, an intervention charged with the politics of freedom. As Chytilová says in Jasmina Blaževič’s documentary portrait of her life Journey (2004): “I was daring enough to want absolute freedom, even if it was a mistake.”

Daisies’ specific brand of feminist politics is a hymn to freedom shouted out with irresistible joie de vivre. This joy is a force of togetherness that is simultaneously intimate and explosive. The film exudes the co-creative vital force of the filmmakers as a group and, on the representational level, the Maries express constant and unabashed pleasure at being together and playing together. That each chooses as her companion, playmate, friend and conspirator another woman, is in itself a joyful feminist affirmation.

The long and hilarious final sequence, which sees the Maries breaking into, devastating and re-patching a luxuriously prepared banquet, ties up all of the feminist layers that this film pioneers and navigates. The feminine role in patriarchal structures is mocked, and at the same time appropriated, when the women improvise a fashion show half undressed, parading up and down the table, their heels trampling over the already dismembered delicacies with enormous fun. The contagious joy that exudes from them in this improvised performance and the masterful and inventive filmmaking drives the scene’s sensuality in ways that avoid any objectification or banality – in fact this scene, can be seen as a culmination of a reinvention of sensuality present in the many other intimate and playful moments of Daisies.

Once the Maries have gobbled, voluptuously squeezed between their fingers and/or thrown at each other, in a magnificent food fight, every single one of the dozens of prepared foods laid out; after they have smashed every dish and glass, they finally decide that they don’t want to be bad anymore. They therefore proceed to fixing the terrible mess they have created with such dedication.

They re-enter the banquet room, now filmed in black and white, wearing newspaper pages tied around their limbs with string, in approximative tops and trousers (which testify to the genius of Ester Krumbachová, co-writer and costume designer of Daisies). With mechanical gestures rendered jerky and slightly robotic perhaps by a high shutter speed (yet another in-camera trick concocted by Jaroslav Kučera), they reset the table by placing the fragments of the dishes in a farce of round shapes while obsessively whispering “If we’re good and hard-working we’ll be happy… Let’s make it all nice… We’ll be happy because we’re hard working… We’ll be hard-working and everything will be clean… When we get everything done we’ll be good and happy…”

Once the operation is complete and the table is disseminated, in some delirious order, with broken dishes and glasses, reconstructed cakes and birds, they climb on it and lay down side by side under the enormous chandelier where they had earlier swung from in inebriated laughter. They sigh with fake satisfaction “I’m happy! … I’m happy too! … Are you happy?… We’re both so happy!… Say that we’re happy. …”. The unapologetic mockery of productivity and male-dominated norms of well-being couldn’t be more brutal.

Daisies is revolutionary, exhilarating, protean, playful, irreverent, brilliant, joyful, outrageous. It is also a daring alchemic experiment. Its cinematographic form brilliantly sustains the adventure of transmuting destruction in a celebration of freedom, vitality and joy.

Leave a Comment