In describing her 1966 film Daisies (Sedmikrásky), Věra Chytilová claimed that it was a philosophical film in the form of a farce.1 Daisies is an unsettlingly powerful example of film’s ability to elicit philosophical thought. The farcical elements of the film add an extra potency to the philosophical questioning of modernity that the film explores.

A farce is a story that employs hyperbolic presentations of character’s mannerisms and their world, usually for comic effect. A farce depends on the ridiculous for its humor. In many analyses of farce as a dramatic style, there is a tendency to deride the frequent use of indecency to produce its humor. Furthermore, farce as a form is criticized for directing the audience away from a higher, more meaningful experience such as what can be found in more respectable and established dramatic forms, for instance, tragedy. Chytilová employs many of the features of farce in Daisies. The film is brimful of hyper-stylized depictions of a recognizable, but also absurd, surreal and even, at times ridiculous world formed through distortions of character’s mannerisms, speech and their interactions with ordinary and everyday objects of their world. For me, what makes Daisies so worthwhile for investigation is the way that the film’s departures from reality are so vividly metaphorical and even recognizable in the modern world, despite the film’s departures from realism. That is, as Chytilová uses avant-garde film techniques to add a layer of absurdity to the world her protagonists dwell in, I find great opportunity to reflect on the world I live in.2 The great achievement of the film is the way that Chytilová explodes the audience’s expectations of reality, but also simultaneously shows them some hidden aspect of their world that might have hitherto gone unnoticed. That is, Daisies uses an absurd representation of the world to show the audience some recognizable truths. Rather than indecent behavior being a property purely of the drama, in Daisies, the improper conduct of the protagonists reveals entrenched indecencies in our world.

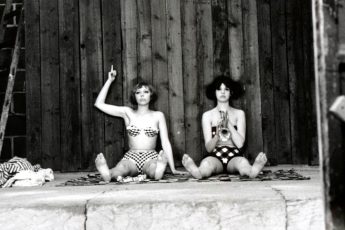

Daisies is a sophisticated film that resists easy interpretation. Peter Hames argues that the only thing that critics can agree on with any consensus is that the film is ambiguous.3 Consequently, the film has meant many different things to many different critics. Even the censors in Czechoslovakia at its release knew it was a film they should be afraid of but were stumped to find a meaningful reason to ban it. In the end, it was the wastage of food that was given as the reason for the film’s banning – an irony which I’ll return to later in this article. Daisies is loaded with symbolism, absurdity, surreal and psychedelic visuals, contradiction, intertextuality, experimentation, and ambiguity. However, at the same time, the film gives the feeling of coherence – one isn’t lost while watching it. Instead, the film’s core message seems to be bigger than any single theme that can be clearly articulated in a sentence. It is rather best seen as a constellation of ideas held together through the protagonist’s unsympathetic buffoonery. That is, the absurd treatment of the film’s world, primarily the way that it is overfilled with improbable, and surreal actions and dialogues that never for a moment resemble a realist plot is where the film’s most important invitations for reflection are made. Essentially, Daisies takes up the question of modern decadence by simultaneously asking, what it means to be decadent and whether we moderns are decadent. The film centers around the exploits of two young women, both named Marie, who decide that as the world is spoiled, they too will be spoiled. The world spoiled here needs to be understood with its connotations of an aggressive and malicious ruining of things.

Consequently, the two women spoil or ruin ‘good’ society and themselves with their reckless behavior. They steal, extort copious amounts of food and alcohol from lecherous men, lie, and sunbathe to their heart’s content, all in the name of being as spoiled as the rest of the world is. Through this plot Daisies treats a wide array of social and philosophical themes, such as a critique of the effectiveness of radical resistance, the extent to which oppressive ideologies coerce behavior, and the oppression, objectification, and marginalization of women in society, to name a few. I contend that it is the farcical way through which they ruin society that gives the film its philosophical strength.

The women don’t just trick men into buying them lavish lunches, they gluttonously devour a ridiculous amount of courses, keeping their suitors willing to part with money through an over-the-top use of stereotypical seductive mannerisms. At once, despite the ridiculousness and humor of such scenes, Chytilová carves a space for reflection. That is, through the hyperbolic presentation of their actions, the film creates a space in which reflection can occur. The Maries are at once acting as the objectified dolls, there only to be fawned on by their lecherous suitors. Simultaneously, through gluttonous over-eating, they explode expectations of how women should behave.

When the audience first meets the two Maries, Marie I announces that she is a ‘panna’, a word that can mean both doll or virgin. Cheryl Stephenson notes that when the first Marie claims that she is a doll/virgin, she is declaring herself to be like a puppet, something both animate and inanimate at the same time. Hence, for Stephenson, it is the puppet aesthetic which is the best way to approach Daisies.4 In a puppet show the puppeteer provides the voice and movement; however, most importantly it is the audience who unify the performance into a single being. In Daisies, this is complicated by the puppet being an assumed role by humans who are having a go at being objects without consciences. Stephenson refers to Heinrich von Kleist’s essay ‘On the Marionette Theatre’ to explain the profundity of the puppet aesthetic in Daisies.5

For Kleist, the puppet acts with a grace that humans can never embody. As conscious beings, human movement is affected in a way which causes the soul of the dancer to shift from its center and into the limbs. For Kleist, “the spirit cannot err where it does not exist”. Furthermore, puppets are immune to the effects of gravity as they are suspended by a force stronger than that which would make them fall. Hence they do not need to rest or recover as dancers do. The conclusion of Kleist’s essays suggests, somewhat apocalyptically, that when humans eat of the tree of knowledge again, we might attain that graceful perfection of having no conscience at all. For Kleist, such a transformation would represent “the last chapter of the history of the world.”

There is a lot to say about Kleist’s essay and Daisies. Much of the rich symbols that fill Daisies refer to the Garden of Eden – to this returning to the tree of knowledge. We see the two Maries, right after declaring their intention to be without conscience, dancing around an apple tree. Throughout the film there are many shots of fruit in various states of freshness and decay and the two Maries are continuously taking bites from apples or peaches. Stephenson suggests that if we understand the girl’s actions as those of beings who have successfully renounced their consciences and become fully puppet-like in Kleist’s sense of the term, then the implications are worrying. “They become dead living beings, beings whose agency can effect change on the world, but is ungoverned by moral constraints”.

Yet despite the malicious buffoonery of the Maries, there is some extra nuance to their actions lurking just beyond the wooden gestures of the puppet-like characters that the puppet ontology does not explain. Every so often, and these are the richest parts of the film for me, they seem to pause and be pained by what they are doing. Constrained by the choice to be spoiled and their commitment to see it through, the women glance at each other occasionally hoping for something more – this is more than a puppet would do, and in my reading, these gestures, when the puppet show is momentarily put aside, are the actual moments of graceful movement. Here we see an inner turmoil that allows us a glimpse into the difficulties of escaping the farce.

Both Marie 1 and Marie 2 suffer from existential angst, they desire to know for certain that they exist. As puppets, they require an audience to give them life, as humans in a spoiled world they have no meaningful connections to give them that sense. As puppets, they look over their recent footsteps and notice the trail of rubbish behind them. “There you are, we do exist” proclaims Marie 1. The two Maries march in unison chanting “we exist, we exist…” before the scene changes to a montage of locked doors. If the unconscious movement of the puppet is all there is, then what are we to make of these images of locks, and repeated shots of train tracks shot in reverse from a moving train and inflected with filter changes, if not that such a view of existence is limited, constrained by a mistaken view of what grace is. Even as they declare their existence and march in celebration, the fact that no color change can grant them access to a new path or a new entranceway is quite a blunt statement.

It is the strong restrictions on their characters that the film imposes on the Maries which demonstrates just how much more to them there is than their actions in the film. The Maries, through their jubilant romping across sensibility and manners, cut through the ideology that sustains those manners. Just as they cut fabric revealing a colorful patterned world beneath, the Maries, as they trick lecherous old men into buying them a good time, reveal the joy of youthful defiance. However, the Maries are also bound by their pact to be spoiled, and even as they express their dislike of the other’s meanness or cruelty, they are still bound to follow. But they are affected, and the effect shows just how far a game like this should go.

This is abundantly clear if we consider the contrast between the film’s credits and its opening scene. In the opening credits the audience see a large industrial machine, menacingly spinning and turning. Punctuating this mechanical movement, we see documentary footage of artillery firing and aerial bombardment laying waste to the populated ground below. The coupling of the strange machine with this footage lends a sense of inevitability or inescapability to the horrors of destructive human behavior. As soon as the credits are finished, we are introduced to the two Maries who are sitting, sunbathing and making very pronounced puppet-like movements while they discuss how spoiled the world is. Even as they speak the scene is interspersed with shots of collapsing buildings. Against the backdrop of such overwhelming and real horror, the question of how to live is suddenly unable to be unanswered in some abstract commitment to the good. This is no place for ethical theory or ideological descriptions of grace. Whatever these two women do must be understood against the contrasting picture of real warfare. Thus, the way that they romp through good society should be seen against the pictures of warfare which really do seem far more hyperbolic than anything affected in the film proper. One can discern in this contrast quite a profound point for the film’s investigation of modern decadence, that perhaps the relationship between the real world and absurd world of Daisies, can be inverted. If the real world produces horror on the scale of modern warfare, then what world really is the over-the-top farce? That is, in a world where individuals, not for a game, really are cutting each other to pieces, it does strike one that any behavior in a world which acts so destructively is going to appear farcical.

I am reminded of a scene in Ernst Jünger’s World War 1 memoir Storm of Steel, in which Jünger recounts going home on leave from the front and seeing two young women off to play tennis.6 Astoundingly, in Jünger’s mind, the two women weren’t properly alive as they didn’t understand the amazing thing he was taking part in just a short train trip away. I am much more sympathetic to Chytilová’s presentation of the question, in that just what can one do when people are so easily and repeatedly destroying each other, and that behavior seems a part of the machine of it all?

Thus, the farce in Daisies has real nuanced and philosophical insight into the human condition, which is not the usual conclusion we make when interpreting farces. In a 1901 essay on farce (republished in 2001) G.K. Chesterton laments the way that works of art are criticized for ‘descending into farce’. For Chesterton, any form of art is as valid as any other if its aims speak to the human condition. The fact that we so deride farce, for Chesterton is because it is fashionable to do so. He reminds the reader that both The Republic and The Frogs are being discussed thousands of years after their emergence. Farce, for Chesterton, captures the experience of joy. Joy is a complex facet of the human experience, and one which art is not so good at describing, yet it remains, for Chesterton, that even to,

the quietest human being, seated in the quietest house, there will sometimes come a sudden and unmeaning hunger for the possibilities or impossibilities of things; he will abruptly wonder whether the teapot may not suddenly begin to pour out honey and seawater, the clock to point to all hours of the day at once, the candle to burn green or crimson, the door to open upon a lake or a potato-field instead of a London street. Upon anyone who feels this nameless anarchism there rests for the time being the abiding spirit of pantomime.7

For Chytilová, the presence of oppressive ideology in everyday life is something that needs to be exploded. As the world as it is in its ordinariness is full of ridiculous social mores and injustices, the hyperbolic treatment of those mores and the extent to which the Maries challenge them demonstrates the artistic merit of farce. Furthermore, the use of the ridiculous to demonstrate the corresponding ridiculousness of the more being challenged makes farce the appropriate form to achieve that goal. Hence, in Daisies, characters literally cut off their limbs without causing injury, open up holes in their sheets to reveal new worlds underneath, or push each other across the frames and into new scenes. With each instance of exploring the “possibilities or impossibilities of things,” Daisies offers a fresh perspective from which to initiate reflection on the presence of ideology in everyday life.

In an early scene, the Maries find themselves in a club where they stumble out of the performer’s entrance, just ahead of the actual performers, two Charleston dancers. The two girls take up their places in a stage-like alcove, surrounded by curtains and begin to act ‘spoiled’. They take out two bottles of beer and glasses just before the puzzled waiter arrives carrying a tray with two beers. The Maries mime a request to the waiter for straws before proceeding to interrupt the show with their reckless antics. As the two Maries bounce around their cushions and tease the guests seated near them we see contrasting shots of flummoxed and exhausted dancers trying desperately to win back the audience’s attention. The soundtrack to the scene, apart from the jazz music that the dancers have set their routine to, is the noise of an excited crowd. The unseen crowd cheer ever louder as the Maries’ antics get progressively more destructive.

Who is this crowd? Do they make noise for us? In my reading, the answer is that this crowd that judge and enjoy the farcical taking-over of the club represent an aspect of the real audience’s world. Consider the current appetite for inane reality television. In my native Australia the most popular television show right now is The Bachelor. I won’t go into just how terrible this show is, but as I sat and re-watched Daisies to write this article I was struck by how well-synched the sound of the crowd cheering was to the earliest and least destructive of the Maries behavior. For example, the crowd noise increases in intensity and volume at the moment when Marie II starts to blow bubbles in her beer through a straw. The film makes a psychedelic treat of the spectacle of bubbles overflowing from the glass with the rainbow sheen highlighted and complemented by changing color filters that capture different aspects of the eruption. The audience must consider though that what they are doing is watching some hoons blow bubbles. It is no surprise that the skillful entertainers are bamboozled by our interest in this unskilled show – what can they possibly do but dance to exhaustion when faced with such irrational interest choices. Let’s face it, the crowd are delighted by inane rubbish, and even worse, cheer louder when the Maries start to harass other onlookers. With the real artistic show exasperated and the crowd getting ever louder, one can pose the question, what good is art for addressing modern decadence when no one will look at it?

Chytilová’s answer is to make our drooling and schadenfreude filled act of spectating the object of art. We the audience are at once watching the Maries act spoiled, and we also are brought into the spectacle as the onlookers. Chytilová invites us to spectate on our complicity in the show and by extension our own contribution to the spoiledness of the world. Thus, the farcical is made all the richer through the audience’s relationship to the unfolding of the farce. That is, the farce is enabled by the crowd’s enthusiasm which provokes ever more destructive behavior from the Maries. Without our participation, it would not exist. In the same way that the puppets require the audience for their subjectivity, this farce breathes and exists as a complete film because of the audience’s involvement in it. As the two Maries romp across normal society’s sensibilities, their destruction acts as a mirror to our own detachment from meaningful existence.

Josef Škvorecký, the towering figure of Czech literature, was a popular mover through the social circles from which the Czech New Wave filmmakers emerged. In his book All the Bright Young Men and Women, in which he recounts his memories of the filmmakers of the Prague Spring, Škvorecký announces the tremendous philosophical depth in Chytilová’s films.8 He recounts that in their first encounter Chytilová explained a screenplay she was trying to film. Škvorecký notes that he failed to see anything of value in the script, and they argued about what he saw as her “rather tedious” support of the dominant socialist realist art form that was popular at the time. However, Škvorecký reversed his earlier judgment when he finally saw the script, declaring that he failed to see just how clever a filmmaker Chytilová was. The way that Chytilová manipulated artistic form to derange what on the script appeared as a straightforward cliché, for Škvorecký speaks to her philosophical credentials. Škvorecký describes Chytilová as “a philosopher and revolutionary of form” capable of transforming the simplest story into “a story of something else”.

It is hence significant that Daisies emerges during the period known as the Prague Spring. In this period Czechoslovakian authorities relaxed censorship standards to be more in line with economic reforms that aimed at shifting the country’s practice of socialism from the somewhat failed Stalinist experiments that did not translate to the Bohemian economy. The period aimed to transition towards what the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia Alexander Dubček famously labelled, ‘socialism with a human face.’ The significance of this time adds an extra dimension to the appreciation of Daisies as the film, instead of exploiting the relaxed censorship to comment on local affairs, used the moment of heightened artistic freedom to make a statement about modernity that took in its sweeping vision, the local as well as the universal. Daisies represents a key moment in thinking through modernity no matter which side of the iron curtain one stood on.

Arguably, it is this philosophic reach by the artists of the Prague Spring that has endeared the period to appreciators. It is true that the artists of the time used the relaxed conditions to make locally relevant political points; however, the Prague Spring saw such a proliferation of films, literature, drama and art that did so much more than criticize the minutiae of mundane life; but instead was able to capture so much of the human experience. Peter Hames contends that the artists of the Prague Spring were moved, not so much by a desire to renounce socialism (although some did); but rather to relish the idea of autonomy.9 He writes that “‘autonomous’ art took on a political function since it represented a dissent from official policy”. What was of most concern was the degree to which any ideology could permeate people’s lives so that they saw the entirety of the world through that ideological lens.

Consider one of the most overtly political films of 1966 (the same year that Daisies was completed), A Report on the Party and the Guests (O Slavnosti a Hostech). The filmmaker, Jan Němec, provoked the ire of the authorities who saw the film as a direct attack on the existence of socialism in Czechoslovakia. Němec himself claimed enthusiastically that the film was not a film about socialism per se, but ideology. The film depicts a group of picnickers who are accosted by a menacing group of ideologues, who at once pretend to be interested in the picnicker’s welfare, and also in assuming control over the group’s activities. As Škvorecký describes the film, “[i]t is evidently a parable about the process which takes place in all modern societies – the adoption of a dominant ideology – and about the destruction of those who do not adopt it”8. The point is, and it applies as equally to Daisies, that the artists of the Prague Spring were keenly aware that where ideology is concerned, everything is political and that the spread of ideology was beyond national borders or geopolitically demarcated regions.

Thus, rather than suggest that everything would be improved if socialism could be replaced by another more liberated political system, Daisies and many of the films of the Prague Spring attempt to demonstrate the poverty of such narrow thinking. Daisies instead reflects on the danger of valorizing emancipation when emancipation is itself a neutral concept capable of producing either autonomy or destructive consumption. The film suggests that a greater focus on what kind of person we should be is perhaps a more important question than under what political system we should organize. When the Maries steal money from a cleaning lady who has been attempting friendly conversation and seemingly longs for a meaningful connection to other human beings, one cannot feel anything other than the deep disappointment of a life of mindless consumption that allows no respect for how we treat others in private relations. On the other hand, the film shows the destructiveness of existing social norms which trivialize the existence of women like the Maries in the first place and that are therefore worth stomping over. That is, Daisies supports the activities of the girls which cut through the oppressive features of patriarchal society while also allowing that rebellion to become ideological itself. Peter Hames argues that it “is possible to identify with the film-makers’ breaking of norms and identify with the girls without approving of them”. This is the key to uniting the disparate themes the film treats. It can, on the one hand offer moments for moral reflection, while also criticizing mores which act as oppressive restrictions on members of society. The film is offering moments for reflection on which actions are morally motivated and which are more socially constructed and dangerous. It is too much, to throw the baby out with the bathwater, as it were, to abandon society entirely, as the film does point to genuinely moral connections between individuals around which we should feel pangs of regret and empathy when the Maries break those commitments.

There is no easy answers in Daisies. The film does not offer a total solution to any moral problem it raises; however it does act as a an enthusiastic call for greater vigilance against our complacency with social norms. The fact that there has been such a wide range of reactions to the Maries’ game suggests that reflection on our reaction to their behavior, in each new scene, is an act of vigilance against offering a total moral or political solution to the problems of modernity. Essentially, the attack on ‘good taste’ carried out by the Maries, reveals the way that social expectations of behavior and morality are only occasionally linked. However, when they are linked there is no good reason to identify with the vandalism of the Maries – they are no heroes.

For Hames, the final sequences of documentary war footage are meant to be seen as analogous to the destructive adventures of the Maries. However, the ambiguity of this final sequence, appearing just after the famous banquet destruction scene reveals the depth of Chytilová’s engagement with modernity. In the penultimate scene the Maries destroy a banquet and comedically attempt to put things right by placing the squashed food and broken plates back on the table. Not only have they acted spoiled but they have been so diminished through the journey that one might be cynical enough to suggest that reform in such a world is nigh on impossible. In this sense Hames is right, their behavior has taken on the significance of the war footage. However, in another sense this footage is obviously more extreme than the destruction of a banquet. I would suggest that Chytilová is employing the war footage, to not only be cynical about modernity but to contend that the fight against ideology is essential to addressing the more serious issues of large-scale destruction that takes place while ordinary citizens are going about their mundane affairs. For me, watching the film in 2018, I cannot help but think of the horrors I hear on the daily news happening all over the world, while I do something inane, like shop online to buy some elusive spice to make a special dinner to end my busy week.

The Czech phenomenologist Jan Patočka, who actively produced philosophical works through the samizdat network of underground publication was, in the late 1960’s, arguing that the direction of human history is best diverted from a detrimental course by a return to what he called ‘caring for the soul’10. Caring for the soul is a kind of opening up of ourselves to our embeddedness in the world. It is an authentic taking account of how our behaviors have far-reaching impact. In my view, Daisies utilized the relaxed censorship to make a forceful statement of something like caring for the soul. One cannot watch the film and not think about one’s participation in mindless consumption. The film pokes the audience into an awareness of the need for awareness. Consider, for example, the prevalence of images of train tracks in the film. The film uses many shots of train tracks, filmed with different filters and from different angles. The connotation to the restrictive way that tracks determine where a journey is to go is clear. These tracks, I take to be analogous to the expectations of behavior. Unlike the Maries, whose challenge to society is at times welcome, and at other times horribly immoral, I find the use of experimental film techniques that shift the image of the train tracks to an image of color or pattern, to be an important invitation to reflect on expectations of behavior. That is the many images of train tracks give rise to meditations on one’s complicity in oppressive social mores (train tracks) which limit the possibilities for those oppressed by the rigidness of those expectations.

Upon Daisies’ release the film was momentarily banned. The ban itself is so infused with irony that it is worth exploring. Škvorecký recounts the comical way that the Czech authorities, led by a deputy of the National Assembly, Mr. Pružinec (a name which Škvorecký finds humorous as meaning something like a Mr. Jack-in-the-box) voiced their complaint. The main complaint was about the wastage of food “at a time when our farmers with great difficulties are trying to overcome the problems of our agricultural production”11. Pružinec’s complaint circulated through Prague and was even read from the stage at a theater recital. Škvorecký claims that the audience took the letter to be a highly funny skit. The nature of the complaint is a perfect compliment to the film’s parting words, “this film is dedicated to those who get upset only over a trod upon bed of lettuce.” Such a provocative dedication, at the end, is a persuasive way of demonstrating that the film reaches far beyond a mere consideration of recklessness and into a philosophical investigation into the decline of modernity. Chytilová seems to be asking, what is the real problem? Instead of asking if a spoiled lifestyle is emancipating or a new kind of oppression, Chytilová asks a much more nuanced question about the relationship of our already spoiled lifestyles and the larger tragedies that occur while we consume and focus our attention purely on our interests.

There are already many works treating the use of color, fragmentation, surrealism, and other film components of Daisies. In this essay, I turned attention to the excellent use of farce by Chytilová, that at once entertains and repulses the audience by showing them an overly stylized, yet all-too-recognizable world. I have argued that the film also brings the audience into complicity with the characters, while simultaneously offering a moment for meaningful reflection on this complicity. These features lift the film to the heights of a magnificent philosophical statement, brimful of rich irony and ambiguity. G. K. Chesterton was right, in the proper hands farce is as capable of speaking to the fecundity of the human imagination and the depth of the human condition. Furthermore, as Daisies demonstrates, it can be the most apt form for making such statements.

Leave a Comment