False Ideals

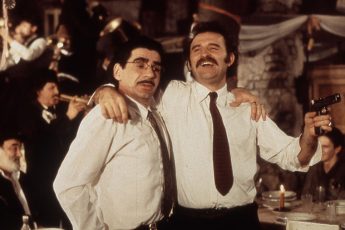

Goran Marković’s Tito and Me (Tito i ja, 1992)

Vol. 22 (October 2012) by Konstanty Kuzma

Zoran, a small (10 or so), chubby boy from Belgrade, worries his parents when in an essay for school, he writes that he loves Tito, the newly emerged Yugoslav leader at the time (the year is 1954), more than them. Determined to get to the root of the problem, Zoran’s father (played by Miki Manojlović, who is also in Underground) even psychoanalyzes Zoran, but ironically, the examination only confirms Zoran’s admiration of Tito. Zoran is indeed fascinated by this man who is constantly on TV and on the radio: besides collecting images of him, the Comrade appears when Zoran is daydreaming; he is, one could say, the “hero” guiding Zoran through his everydaylife. Still, it is not his overflowing admiration for Tito that motivates him to write this essay, but Jasna, a skinny girl who is taller and older than him, but whom he convinces to go out with him. When Jasna announces that she is to leave Belgrade to take part in the “March Around Tito’s Homeland” – an ideologically connotated trip retracing the history of Tito and the Partisans – Zoran is desperate, until his teacher announces an essay contest that will allow the winner to take part in this very march. But though Zoran does get to participate in the March, Jasna’s modest interest in Zoran soon dissolves, while malicious Comrade Raja (who is supposed to take care of the children participating) begins disliking Zoran.

Although the story of Goran Marković’s cult comedy is narrated by little Zoran, the film is less about childhood in Tito’s Yugoslavia than it is about Tito’s Yugoslavia as perceived through children’s eyes. Zoran’s crush on Jasna or his admiration for eating appear genuine, but they are likewise catalysts for showing the ideological weight of life in Yugoslavia: Jasna soon falls for an older, and more “important” pioneer, while Zoran’s habit of nibbling off the wall is spotted by his uncle, who, skeptical of Zoran’s parents pro-Socialist attitude, calls him a “degenerate”. Indeed, Zoran’s home appears to be a representation of early Yugoslavia’s different streams, with the two families and three generations sharing the apartment constantly being in discord about political happenings. Zoran – drawn between the religious root of his family, the ideological fundament of Socialist Yugoslavia, and, finally, his emotional inclinations (which turn out to be the most reliable force that drives him) – thus represents the ordinary, well-intentioned Yugoslav citizen instrumentalized by political elites. This instrumentalization, one should add, does not end with Tito’s Yugoslavia, but assumes ever crueler dimensions. After all, in 1991, as Marković’s film is being finished, a wholly new era of Yugoslav history begins.

During the moderately successful march, we find out about some problems Yugoslavs were facing during the early years of Tito’s reign – the demise of the intellectual elite, attacks on churches, and poverty. But the dissolution of Tito’s spell doesn’t arrive by way of a socio-political analysis; it is the very ideals propagated in Tito’s Yugoslavia that are rejected by Marković. The March around Tito’s Homeland culminates in Kumrovec, Tito’s hometown, where Zoran is to recite his poem about his admiration of Tito. Instead, however, Zoran points to a “misunderstanding”:

I had the honor to represent my school at this grandiose March. But I haven’t deserved it. I’ve done something that no pioneer of Tito’s would do. In my poem, I didn’t say the truth when I wrote that I loved You more than Mum and Dad. Everyone knows that I love Mum and Dad more than anything. My grandma, too, all the folks back home… [etc.]

Indeed, it seems inscrutable why a child should prefer political figures over his own guardians. In Soviet propaganda, most notably in the myth of Pavel Morozov – a boy who supposedly denounced his father to the authorities – the emotional binding between child and parent is often forgotten. After the fall of the Soviet Union, some historians claimed that Morozov’s tale was based on questionable witnesses’ report and is thus devoid of any sort of historical credibility. For the understanding of Soviet and Yugoslav ideology, however, this epistemological barrier is secondary. It is the fact that Morozov’s tale (or that of Zoran) could even serve as an ideal that is truly bothersome…

Leave a Comment