Flying Away From Nowhere

Miguel Ángel Jiménez’ Seagull (Chaika, 2012)

Vol. 23 (November 2012) by Anastasia Eleftheriou

The Seagull (Chaika) is a film that emerged from a co-production between Spain, Georgia and Russia supporting Spanish director Miguel Ángel Jiménez to create a film about people living in today’s uninhabited territories along the borders of the ex-iron curtain. According to the director, the film was inspired by a photographic project by Norwegian photographer Jonas Bediskten (magnum photos) showing kids playing with wrecked metal parts of space-rockets in the remote areas of Kazakhstan.

KAZAKHSTAN. 2000. Debris from a recently crashed Soyuz space rocket lies on the steppe. © Jonas Bendiksen/Magnum Photos

KAZAKHSTAN. 2000. Debris from a recently crashed Soyuz space rocket lies on the steppe. © Jonas Bendiksen/Magnum Photos

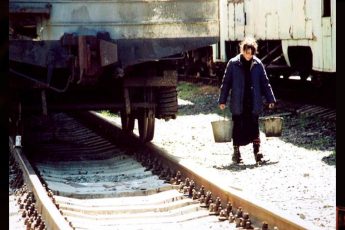

Chaika shows the different ways in which people can relate to their homeland. A pregnant prostitute follows a sailor back to his home, an isolated farm in Siberia. In this white landscape it is impossible to distinguish the border between land and sky. The only elements disrupting the endless white are falling metal parts rockets leave behind as they fly over the area. After a family drama in the farm in Siberia, the woman and the sailor decide to take their child and move to the steppes of Kazakhstan. Here, in her own country, the woman will have to confront her own sense of belonging. Obviously warmer, we are again confronted with a deserted living space. The only signs of human intervention in that desert are rocket stations and railroads. In Chaika, two people make their own decisions in life, settling down or leaving what they consider home. In a parallel narrative, the film depicts the grown up child of the woman in the search of his mother’s story, and hence, of his own.

The film’s beautiful photography allows us to travel in a world where the prevalent reality of the people is the connection they have with their natural environment. Frozen Siberia and the steppes of Kazakhstan are no-man’s-lands with which people have identified themselves for centuries. The many shots of landscape and nature are not only breathtaking, but seem to serve the director as a means to show the emotional reality of his characters. Chaika has very few scenes with dramatic acting. But the deep emotions of the characters are reflected in the imposing natural landscape. A similar approach to landscape has been introduced by Antonioni, whose characters are identified with and transformed by the landscape they inhabit. Although Antonioni was, of course, mostly critical about both his landscapes and its characters, Jiménez succeeds in showing that the impact environment has on people is inevitable.

But even if the film uses landscape in this symbolical way, Chaika gives the feeling of a documentary more than that of an allegory. The realistic sense of the film is already present in the storyline that is based on true stories the creators of the film witnessed or heard of during their own travels around Kazakhstan. Despite the fact that the film is shot in Georgia instead of Siberia, and that it also includes many fiction elements, the director has succeeded in making us feel as though we are witnessing reality. The actors seem to fit very well to the surroundings (although the main characters are Georgian) and to their roles, and there are some scenes that seem both improvised and realistic. Especially the traditional song between the two brothers and the mourning song at the funeral in Kazakhstan give the film a documentary-like feel.

Apart from being a film about the relationship of people with their homeland and a no man’s land, Chaika is also a film about art. The extreme weather and the complicated social conditions under which the crew worked make the film an inspiring example of filmmaking. Apparently, one can do films with a minimum budget, even if one has to go the end of the world to do so.

Leave a Comment