Prosecutors and Correspondents

Srđan Keča’s A Letter to Dad (Pismo ocu, 2011)

Vol. 16 (April 2012) by Moritz Pfeifer

In his documentary A Letter to Dad, the young Serbian director Srđan Keča writes a letter to his deceased father. The father’s past is as mysterious as his death. Nobody in his family knew that he was severely suffering and that he was living with death for years. But his life was also troubled by other experiences he decided to take into his grave – the father was a volunteer for the Serbs during the post-Yugoslav wars. When Keča shows some archival footage the father shot of his kids, and comments that his father preferred to stay behind the camera, we understand the motivation for the film.

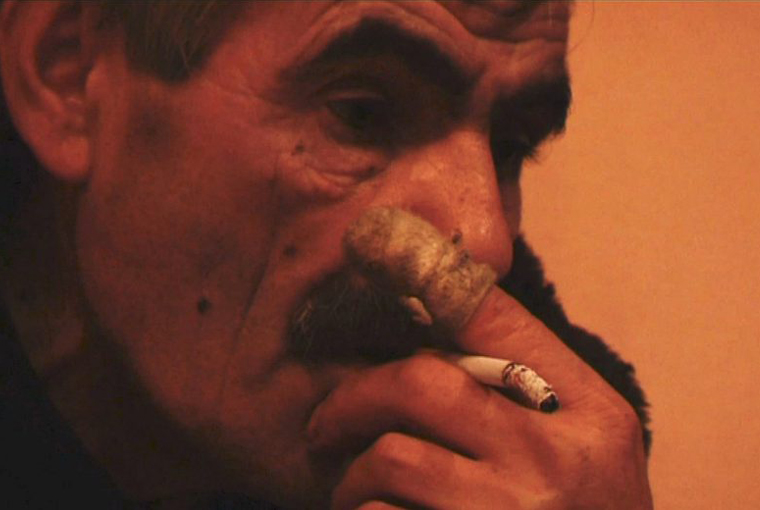

It is up to the son to look for the pictures that the frames of harmonious family life didn’t capture. Keča thus interviews war comrades, family members, and friends to puzzle together a more accurate portrait. But the people he interviews reveal more about themselves than about his father. Most strikingly are the comments of another volunteer, still dressed (for the occasion?) in a military suit. The man tries to remember Keča’s father and his friend, but each attempt to recall some anecdote quickly evolves into ideological statements about the war. Although Keča is not in a real dialogue with the man, he somehow tries to give justifications to hypothetical questions, such as whether the Serbs are the only ones to blame, etc. Things get rather uncomfortable when he reveals to Keča that he is the son of a mixed marriage, as if he were disclosing a cruel truth everyone had avoided telling the director. With such interviews, the film portraits a touching account of a post-war generation conflict. The almost inevitable clash is already prescribed into the film’s motivation: a son’s search for explanation in front of the denying attitude of his father.

But what distinguished Keča from the post-World War II generation of the 60s, the post-Vietnam generation of the 80s, and perhaps from his own post-Soviet Union generation, is a lack of accusation. Here is a director looking for a truth he does not seem to have found before making his film. Indeed, Keča is reluctant to tear conclusions from the sometimes shocking accounts of the people he interviews. In that, his film differs from the inculpating discourse of other films exploring the past. Suffice it to recall the grotesquely devout mentality Andrej Ujica’s recent Autobiography of Ceausescu attributes to the Romanian people. If Ujica’s approach permits one to laugh in retrospect, Keča forces one to raise one’s eyebrows in astonishment. Reality is banal. There might have been a war, massacres, and expulsion but after all, it’s all about keeping one’s house, driving a car, raising a family. Why one might go out to kill people is a second degree question. In Keča’s film, it seems almost beside the point.

It would have been nice had there been more material showing this. As it is, the film passes rather quickly from one decade to the next without giving the different time periods space to develop. The director’s mother, for example, sticks to a version of the past where her husband was enrolled to go to war and did not participate as a volunteer. But it is unclear whether she really believes this, or whether it is just a sign of loyalty to her husband.

But nevertheless, for a film that is under one hour long, Keča’s A Letter to Dad convincingly defends an alternative approach to the cumbersome past at the root of so many generations divided by war and peace. Instead of playing the role of the prosecutor, Keča decides to write a letter asking sincere questions without having prefabricated answers of his own. This more conciliatory approach might be less insurgent, but it is at least as gripping as the former one.

Leave a Comment