Menacing Peasants

Sergei Loznitsa’s Portret (2002), Peyzazh (2003)

Vol. 16 (April 2012) by Moritz Pfeifer

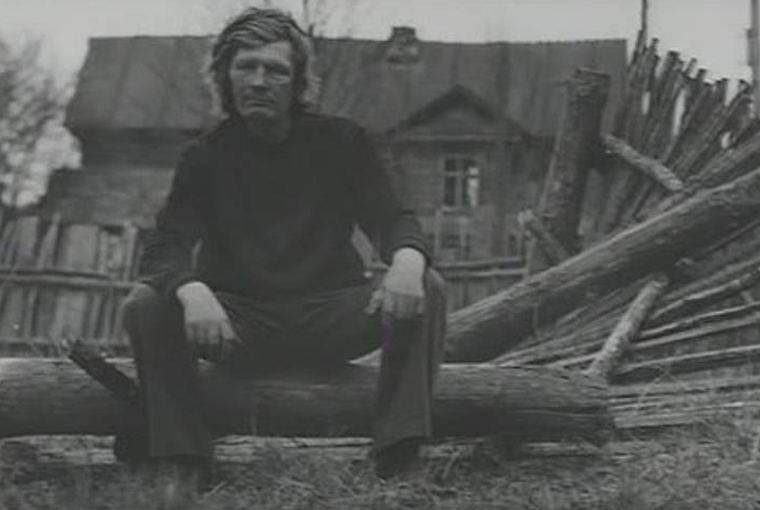

Two early documentaries by Sergei Loznitsa’s deal with peasants. The first, with the title Portrait, depicts photographic-like long shots of rural workers. The second, called Landscape, is entirely made up of left-to-right tracking shots of people waiting at a bus stop in a small town called Okulovka. Aesthetically and thematically, these films have many things in common. Both focus on the working class of rural Russia. By far the majority of the people portrayed in both films are old. Portrait depicts not one child or adolescent and the few smooth faces of children and teenagers at the bus stop in Landscape appear rather exotic in between the bulk of wrinkled faced seniors. Many portraits in the first film are set against a background showing ruinous buildings. Torn down houses, falling apart barns or rotten working tools provide the setting for these pictures. What both films seem to tell us is that it is only a matter of time when there will be no generation left to keep these communities alive. Peasant life is deteriorating. In the mid 1990s people aged sixty and above made up more than twenty percent of Russia’s rural population, twenty percent more than in the 1970s. More than 20 million hectares of cultivable land has been abandoned since 1991. Rural life belongs to the past and is unsuitable for a society way into the urban lifestyle of post-industrial prosperity.

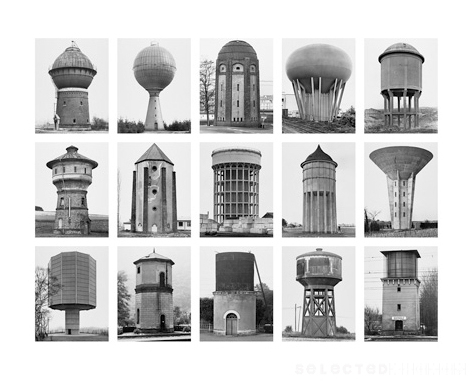

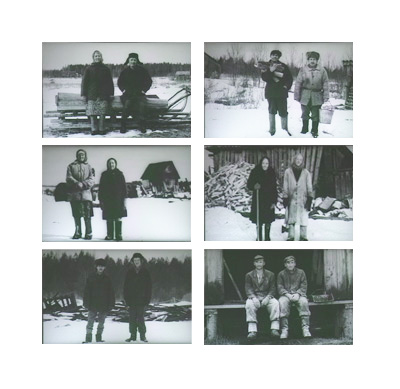

But there are important differences between the two films and the way in which they represent this change. In Portrait we see whole body portraits simulating still life photographs. Sometimes these photographic stagings have a comical effect. For example when a man cuts wood without moving his saw in one scene, or when a woman stands paralyzed in the middle of the road pushing a cart in another. The still-life imitations in Portraits are archival. Frame after frame we see peasants of an indeterminable epoch, looking back at us as if from out of a photo album. These people are almost like objects, statues maybe, of things we love but for which we no longer have a use, whose customs might have been important once but no longer affect us. Without wanting to appear cynical, there is a striking similarity of these these pictures with the archival photography of Bernd and Hilla Becher. The Bechers are known for their portraits of abandoned industrial objects that they categories in columns and rows, for example of Water Towers. The workers in Loznitsa’s Portrait are much like these industrial objects. They are beautiful, but outdated and appear superfluous in a post-industrialized world. Is the gap between an abandoned Water Tower and an all-glass office building not very similar to the gap between Loznitza’s workers and a thirty year old businessman in a suit?

Bernd und Hilla Becher, “Wassertürme”; Sergei Loznitsa, six frames from Portrait

Although similar in theme, the second film lacks the archival method of the first. In Landscape the camera is always in motion gazing over the expressions of the people it captures. Unlike in Portrait, there is not one scene showing a person from head to toe. Why, then, is it called “landscape” when all there can be seen are faces? Maybe the film’s picturesque title can be explained through the painterly impression it conveys – it is also Loznitsa’s first film shot in color, whereas Portrait was shot in black and white. Someone commenting on IMDB remarked that Landscape reminded him of Bruegel, who was known in his time as the painter of peasants. In a critique of Loznitsa’s My Joy, I have compared some of his scenes to the sinister faces in Bosch paintings. Indeed, there seems to be a fascination for grimaces in some of his films, a fascination especially noticeable in this one. This then, seems to be the major difference between the two films. Portrait seems to be about the disappearance of rural life, and it documents this disappearance in a distanced, quasi-scientific way. Landscape is exactly the opposite. It is not a film about the decline of an objective occurrence, but about the way in which that occurrence is symbolically perceived. The fascination for rustic hideousness in Landscapes seems to be part of a social imagination triggered by Russia’s socioeconomic development since the mid 1990s. Historically, the image of menacing peasants appears when social order changes, when the poor from the hinterlands mingle with the lives of wealthy urbanites. At least since the middle ages, hideous peasants express social fear for loss of stability and economic decline. This fear is never only on the side of the wealthy but can be part of the peasant’s own efforts to leave “simpler” values behind. Images of menacing peasants are projections of the loss of security in times of social change.

The appeal for the grotesque, darker visages of peasants goes way back into the middle ages where songs, literature, and those who were able to read and to listen to music opposed the evil villain to the justly knight. Even Saint Augustine distinguished between rusticus and urbanus which he thought as oppositions analogous to vulgar and civilized. The hideous metaphors connected to rural life-style are traditionally set up against a closed, clean and cultivated environment. But the image of the peasant as a menace are perhaps especially apparent whenever a society is in the need to come to terms with the darker advancements of social change. It is no coincidence that images of deformed peasants, rural fools, and lowly rustics flourished in the late middle ages, during the growth of cities, and a rising economical independence among the middle class. Dante, witnessing the extension of Florence in the fourteenth century, nostalgically dreams of former times of nobility and prosperity in the Paradiso: The mixing together of persons has ever been the beginning of harm to the city.” (Line 67-68). He cites a list of well-known noble men, forgotten because they could not compete with the rise of merchants many of whom came from rural, unaristocratic backgrounds. His poem is like a reminiscing lament.

It might be useful to take a closer look at the conditions that led to the distrust of peasants in late medieval Italy, as it bears striking similarities with the transitional period of post-communist Russia. The population of most major cities in Italy increased five-fold between 1000 and 1400 and a similar, although less drastic urban ascend could be observed in France, Germany, England and the Netherlands. Rural migration was due to a commercial revolution. A rising class of merchants, traders and businessmen needed workers and man power for their fabrics, markets, and trade. This left entire villages abandoned, as the peasants left the lands to seek wage opportunities in towns. But the commercial revolution also resulted in poverty and destitution. The merchant Domenico Lenzi reports that there was constant shortage of food in Florence. At the end of the thirteenth century, when Dante was writing in Florence, the city could provide its inhabitants with food only through five months of the year, which triggered a need for importation which, in turn, lead to more workforce moving to town. But the merchant’s rise of wealth and power over the noble men wasn’t welcome to all. Aristocratic minds like Dante showed their contempt against the “nouveaux riches.” The rising power of the merchants threatened the influence of the established nobility. Facing this change, advocates of hereditary nobility could project their fears of social disorder onto the image of peasantry. Rural stupidity could account for political failures and savage behavior could explain the ruined conditions in town. Boccaccio, who lived a generation after Dante also complains about Florence’s general degradation. In a letter from 1360, he says about the gaining power of the wealthy that they had been “taken from the plow and elevated to the highest office in the state.”1

But, ironically, many so-called nobles who scorned the “peasant-like” conditions in Florence, were themselves of peasant origin. Thus the richest family of the time, led by Corso Donati, was in a feud with another family, lead by Vieri de Cerchi. The Donati family had simple origins and were only knighted some decades before, but the Cerchi’s nobility could be traced back to antiquity. The leader of the Cerchi’s, however, was more popular in town and also richer. He was called ‘the Baron’ by the people, a name indicating both his power and the “nobility” of his character. Donati himself called his opponent an “Ass”, a degrading name more fitting for the class where Donati himself came from. Nobility was no longer a matter of heritage but of wealth.

What happened in Italy at the end of the thirteenth and at the beginning of the fourteenth century happened again at the end of the nineteenth century as a result of the industrial revolution. By the mid eighteen hundreds, the social order in Russia changed through the emancipation of the serfs. But change was slow, fueling urbanization because peasants migrated to towns in search of work. As with the commercial revolution of Florence, a new working class emerged consisting of labor forces, and industrial entrepreneurs. This new class drew away the younger generations from the countryside. But the more successful these migrants made their living in town, the more they wanted to rid themselves from their origins, defining their lives through the wealth of the aristocrats with whom it was easier to share wealth than social recognition. As in Florence, the image of the menacing peasant turned up, first, because the aristocrats feared the deprivation of their wealth and power. But this fear was also supported by the the emerging class of wealthy peasants who, similar to Donati in Florence, stigmatized their own social origins. In a way, they imitated the manners of the class they tried to belong to, which was a class that, technically, was in decline. Anton Chekhov portrayed this social change in many of his works. Take Lopakhine for example, the rural serf in the Cherry Orchard who ends up buying the land of his impoverished masters. In one scene, he remembers how his mistress used to console him as a child:

‘Don’t cry, little peasant,’ she said, “You’ll soon be as right as rain.” [Pause]. Little peasant. It’s true my father was a peasant, but here am I in my white waistcoat and brown boots, barging in like a bull in a china shop. The only thing is, I am rich.”

For Chekhov’s Lopakhine, getting rid of the etiquette “peasant” seems more important than wealth. His motivation to acquire property can be explained through a desire to be recognized by the wealthy not to benefit from material goods.

Evil peasants threaten to steal wealth from society, but more importantly they jeopardize social order. This fear, as it was widespread during the commercial revolution in Florence or the industrial revolution in Russia, seems to have gained significance again during the last decades in Russia. As in 14th century Italy and 19th century Russia, the fear for peasantry leads back to social change and a rising anxiety among the wealthy to be struck by poverty. Again, this change is accompanied by urban-rural inequalities.

Since the falls of the Soviet Union, little has changed in Russia’s country side. Whereas large cities resemble boom towns, the countryside in Russia is practically untouched by modernization. In Russia’s rural areas and poverty stricken outskirts, the services that are of use for the elite practically don’t exist. For example, some peripheral regions lack telephones, and because it is cheaper for the more wealthy in theses regions to buy cell phones, communication networks can’t get there. Entire steps of technological and infrastructural developments are skipped because those who can supply themselves with what they need are able to buy it. The Russian geographer Boris Rodoman writes that “owners of bio-toilets, air conditioners, and buyers of bottled drinking water are less interested in mass sewage treatment and the quality of piped water and rural air. The clean and lively space equipped with modern conveniences lessens, shrinks around the elite, and the remaining space is driven into dirt and darkness.”2

The economical conditions in rural Russia are the worst in the country. Between 2002 and 2004, the increase of rural poverty was as high as never before. The sociologist Michael Burowoy summarizes that that Russian society is being driven “into two mutually repelling poles – a male-dominated pole of wealth, integrated into the hypermodern flow of finance and commodities, and a female-dominated working class underworld, retreating into subsistence and kin networks.”3 Those who can’t make it into the ‘hypermodern’ society become increasingly marginalized both within society and within their own family life. When it is considered necessary to represent a life-style defined by success and prosperity, signs of simple life turn into stigmata. Life breaks down in vicious cycles with resignated men soothing their guilt of failure with alcohol. Both of these phenomena are visible in Loznitsa’s film. A striking majority of the people in Landscape are women, and the two younger men he films meet to share a bottle of hard liquor. But the stigmatization of peasant faces is the most visible aspect of the film. It is not exaggerated to say that these women look as though they come from hell. Peasant life is not bad, they themselves are evil.

Sergei Loznitsa, Landscape

It is important to compare the peasants in Landscape to those in Loznitsa’s other film. Portrait is a film unconcerned with individuals. There is no additional point of view making moral claims about human conditions. In this film life is bad, not the people living it. There might be notions of nostalgia in Portrait, but it refrains from considering rural life as something better. Showing menacing peasants, on the contrary, is an aesthetic choice. It doesn’t necessarily mean that Loznitsa shares the point of view he depicts in his film, but it might suggest that such a point of view is shared by a part of society.

Indeed, it is not surprising that in such a society of social change, being a peasant is not only a profession but also a value. The devastating conditions in Russia’s hinterland are evil because they are opposed to modernization. These conditions are all the more menacing when most of the people who can call themselves modernized don’t live in social and economic stability. However, peasants do not make up a significant amount of the people disposed to compete with the employment struggles of urbanites. Their poverty never significantly transformed into a desire to enter the economical possibilities opened up by a free market economy. Their poverty cannot stand for a real menace. Above all, their poverty is aesthetic. Images of destitute homes trigger fantasies about the possibility for poverty to strike the social advancement of those struggling to climb the social ladder. At the foot of this latter stand the peasants pulling at the pants of the entrepreneur fighting to move up.

In the early 2000s, when Loznitsa shot his films, Russia’s economical conditions rapidly recovered from the turn of the 1998 crisis. However, more than half of the people occupying higher social positions, such as managers, were still afraid to lose their job in 2004. 4 It is difficult to examine what exactly is at the heart of this fear. Many factors might play a role including experiences from the previous crises, as well as from the general poverty Russia had to face throughout the nineties. However, the two criteria that nurtured the fear for peasants in 14th century Florence and 19th century Russia – social change and economical instability – seem to be decisive for today’s fear of peasants. Loznitsa is not the only one capturing images of hideous peasants. Last year, Zvyagintsev’s touched on a similar topic with his film Elena. The film is about a poverty-stricken family living in Moscow’s periphery. The mother of the family infiltrates the life of a metropolitan entrepreneur and inherits his wealth after killing him. Zvyagintsev wanted to call his film “The Invasion of the Barbarians” but decided to give it a less politically incorrect title.

Loznitsa’s two films about Russian peasants are like two sides of the same coin. Portrait is like a requiem. It is the expression of a loss, a slightly nostalgic documentary about the disappearance of a social group. In that sense, it might even share some elements with Dante’s enumeration of Florentine nobility. When society changes, there always seems to be the need to mourn over the things left to the past, and to fear for the things left to the future. But in Portrait, lamentation is subtle and perhaps overshadowed by the archival approach of the film. It remains hard to dream about rural harmony watching Portrait. Aesthetically, the films looks more as though Loznitsa was hired by the agricultural ministry to do a photographic census of Russia’s rural workers. In Landscape lamentation turns into fear, sympathy into repugnance. This film brakes with the archival approach of Portrait introducing a socio-psychological point of view through which the peasants are perceived. This point of view regards peasants as menacing. Ultimately, the film has more to do with the people who project their fears on peasant poverty than with the peasants themselves. But to pair wealth and poverty with good and evil also affects the way in which the poor see themselves. If being poor is a stigmata, it can no longer be a matter limited to perception. Loznitsa, for sure, does not doubt the fact that these stigmata can easily translate into self-destruction.

Leave a Comment