Twilight Zone

Sergei Loznitsa’s Artel (2006) & Northern Light (Severnyy Svet, 2008)

Vol. 17 (May 2012) by Moritz Pfeifer

In 2006 and 2008, Sergei Loznitsa shot two short documentaries in Russia’s arctic settlements. The first film is called Artel, which means “team”, “crew” or “collective.” The film opens in a ruinous shack from where the camera gives an overview of the icy landscape. We then follow a day at work of a group of fishermen. They cut holes in a frozen lake with a chainsaw casting their fishing nets through the openings in the ice. Once the nets are joined, the fishermen wait for the fish to do the rest. There’s no hurry. The camera keeps a distance from the workers. Like in the opening shot, it pretends to look out from a window without being seen, leaving the fishermen like miniatures in the cold. The second film, Northern Light, portrays a day in the life of a family in another region of Russia’s extreme north. We see the father going out to work early at dawn, before the two girls wake up to have their hair done. In the meanwhile, the grandfather is working in the stable and at the end of the day everyone unites for diner. Morning and evening are introduced with images of fire burning in an oven.

Loznitsa likes oppositions. He often presents similar themes from two contradictory points of view. The first film exploits the harsh conditions of working in the arctic cold. In this film, the scenes depicting the workers are interrupted by images of an ice storm. The second film, although set in a similar environment, mostly takes place in cozy interiors and the ice storm is countered by a bed of coals.

The differences in his two earlier films about peasants, Portrait and Landscape, are very similar to the differences between Artel and Northern Lite. Portrait and Artel are both black and white. They use steady long shots to observe rural life-style, and agricultural working procedures. Both films could easily be set in another time. If it weren’t for the chainsaw and the motorized sled one could very well think that those fishermen are from the 1920s. The atmosphere in these films is not only calm but almost static. This is another recurring theme in Loznitsa’s oeuvre. His depiction of workers is never teleological. Unlike the well-known TV-documentaries that follow machines and men working on the finalization of a visible product, Loznitsa shows little interest for the results coming from such work. This concealment of a ready-to-sell product at the end of a working chain is already present in his first film Today We Are Going to Build a House, where a group of construction workers are captured building a house. But the house is hardly ever visible in this film and the workers anything but in the verve. Progress is not part of this film. It might also help to recall some scenes in Fabric, a film about the production process in a fabric. If it weren’t for the titles “Steal” and “Clay”, it would be impossible to tell what exactly the machines in the fabric produce.

Loznitsa hides the results that the workers he films try to accomplish as if to suggest that there are other reasons for work than a final good. Indeed, the motivation of the fishermen in Artel, of the construction workers in Today We Are Going to Build a House, and of the exhausted factory workers in Fabric is the mystery of these films. There is neither a product nor wage, only an endless cycle of slow, repetitive movements. Work for work’s sake. The workers themselves are so much part of this cycle that it is not possible to see them as individuals. Post-communist dawdling is obvious here. Loznitsa’s full length shots capture the workers as if the meaning of their life still depends on the exertion of collectivized labor-ideals.

This point of view of working life as a static occupation with no beginning and end is juxtaposed to a second one. Here, the focus is on the individual not on the work. If the workers in the black-and-white films Portrait, and Artel are anonymous miniatures in a more or less hostile environment, Loznitsa goes for close-ups and individuality in Landscape and Northern Light. These films, perhaps to underline their contemporary setting, are preferably shot in color. In the black-and-white films, there is also no dialogue, which adds to the anonymity of the figures they portray. The conversations in the colored films establishes characters with emotions and attitudes.

Of peculiar interest is the use and absence of irony. In one scene, for example, a worker cuts a circular hole in the ice. He then puts the saw aside and jumps in the middle of the circle. What looks like a self-defeating gesture, is in reality only a way of loosening the thick ice. But the repetitious jumping of the worker in the middle of the floating circle adds a slapstick-like element to the scene. One might recall Bergson’s famous formula of how comedy is produced. For the French philosopher, comedy describes something mechanic in something living. Indeed, the workers in Loznitsa’s black-and-white films are shown in a way that makes their work appear automatized. They are like little parts of a large machine. In Northern Light, this ironic element is absent. The rural work done by the family in this film is individualized, it is never mechanic because there are no repetitious movements at stake. Whenever the film shows someone working, there might be a sense of tradition involved but the first question one asks in these scenes is how the particular character will do his work, not what precicely he is working at. Here, work is alive in the sense that the human being is in charge of his activities and not the other way around.

Of course, this opposition between workers who are symbiotically unified with their work, and workers who have a life independent from employment can be paralleled with Russia’s socioeconomic break from Communism. Do the old-looking documentaries like Artel, with their themes on stagnation, and collective labor force not recall the ideals and realities of planned economy? And conversely, do the colored films centered on the individual not represent the ideals and realities of free market economy?

The working conditions in Artel look beautiful from afar, but are neither profitable nor cozy. The shattered houses, the ruinous shack in Artel‘s first shot speak for themselves. But these films are also cynic, because the feeling that everyone is part of a homogenous comradeship is an illusion. Outside of the working-class society, there is always someone who can laugh at the deindividuation of his fellow men. The second film gives a feeling of coziness and the film’s characters are more independent. Working is considered a means, not an end in itself. One works to have dinner with family and friends, to watch TV, to listen to the Radio.

But one should be careful not to see Northern Light as a hymn to the advantages of liberal economy. Even though the family depicted in Northern Light seems to represent a quasi-sacred alternative to the chaos associated with other parts of Russia, the two films are two sides of the same coin. It may very well be supposed that the lack of exterior shots in Northern Light could be substituted by those depicted in Artel, and conversely, that the interior shots in Artel could resemble the lives of the workers in Northern Light. Loznitsa’s two films about Russia’s arctic regions have to be seen in a kind of dialogue. One sometimes even has the feeling that some scenes in one film are deliberate follow-ups in another.

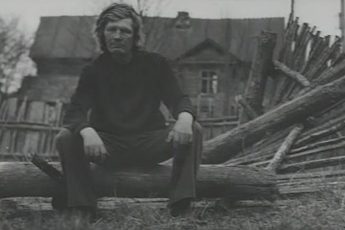

Sergei Loznitsa, Northern Light

Sergei Loznitsa, Artel

In the first example, the bucket-carrying man moves away from the picture. There is a boat on his right, and he is walking up a hill. Exactly the same scene can be found in Artel, although shot from the top of the hill. One can find more such links in other scenes. It would therefore be wrong to suppose that Loznitsa uses one film to express a form of regression, and then respond with a second one expressing progression. His sequel only feigns contrasts. The reality in both films would probably look very similar. The only thing that changes, then, is the point of view. This is what matters. Only a small amount of beauty, happiness, and wealth depend on exterior circumstances. Most of it depends on how we see things.

Leave a Comment