The Radical Core of Polish Experimental Cinema

Łódź’s Workshop of the Film Form

Vol. 147 (September 2024) by Anna Doyle

Founded in 1970 by students from the cinematography department of the National Film School in Łódź, the activities of the Workshop of the Film Form are still regarded as a key moment in Polish experimental cinema. This collective of filmmakers responded to the emergence of conceptualism and neo-constructivism in Polish visual art through cinematography, aiming to create an alternative film experience. The collaborative efforts of the group bear many similarities with other experimental film groups in Eastern Europe, such as kinema ikon in Romania or The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia. Interested in the purification of the filmic form, their experiments with cinema served as radical provocations aimed against classical cinema, which they deemed contaminated by other arts – especially literature. Emerging from the margins of the Film School in Łódź, their formation, initially informal, would institute a more established entity within the school in the later 1970s and become widely influential in experimental practices in Poland. The group’s official status as a film club allowed for professional development of film projects through collaboration, thanks in part to a privileged access to film stock, notably 35 mm film. The group was male-dominated, with notable members of the WFF being Józef Robakowski – the most prolific core member –, Paweł Kwiek, and Kazimierz Bendowski, among many others. In this article, I will analyze some of the key features of this neo-avant-garde movement, inquiring into the group’s aesthetic, conceptual, and political intentions.

Films developed at WFF focused on film as action and live performance, raising fundamental questions such as: how are films made, what is the relationship between films and life, and what are sound and image, light and projection? Film was seen as a meta-art practice encompassing art and life and how we perceive the both of them. Furthermore, disinterested in the aesthetics of slow contemplation, they often “attacked” the viewer’s perception to indirectly deconstruct ideological or narrative aesthetics. They were driven by a desire for liberation from aesthetic conventions with no concessions being made to public taste. Disregarding socialist content and nationalist form, their aim was the purification of form without a straightforward subject or content – the referent in semiotic terms was often the film itself. While Józef Robakowski’s works might come off as apolitical formal experiments focusing on the cognitive aspect of perception and the mechanics of the medium, those of Paweł Kwiek were more ironic engagements with sound and image barriers, often playing around with the miscommunications permeating Communist bureaucracy. This tended to make his films formal as well as political: he reassembles different types of footage in 1, 2, 3… Cinematographer’s Exercise (1, 2, 3… Ćwiczenia operatorskie, 1972) in which portraits of Lenin and Socialist parades are assembled with the aid of visual effects and colorful, geometrical experimentations, inserts of Dadaist gestures, and psychedelic rock music. The visual playfulness vis-à-vis political imagery forms an artistic “détournement”, as the situationist Guy Debord called the technique of “detouring” capitalist mass culture in cinema. Along these lines, WFF works can be understood as an ironic turning of Communist imagery against itself through playful experimentation as a way of politically engaging the spectator without taking a specific stand. On the other hand, Kazimierz Bendowski mainly experiments with light projected onto cityscapes, for instance in his city light symphony film Centrum (1973), and has the camera wander through the marginal edges of the city: the gritty and abandoned zones of the Socialist city are framed in a structural venture in his film An Area (Obsza, 1973).

Needless to say, if in the West, say during the New American Cinema, experimental filmmakers such as Jonas Mekas or Stan Brakhage were looking for relief from capitalistic hegemony in the film industry, WFF wished to be relieved from state-funded cinema and government officials and conventional artistic guidance in film education. However, the government accepted the existence of the WFF as a film entity within the Łódź Film School. If members of the WFF were critical of Communism in private – as Robakowski would claim in later interviews –, the WFF was not straightforwardly dissident. In general, there is a misconception about what “radical” meant in Eastern European experimental cinema – oftentimes, radicality did not entail political transgression as such, but rather an engagement with formal concepts as a way of moving away from the political art of institutional cinema, engendering what Dina Iordanova called “apolitical political films”. Anna Misiak explains the tangibility of Polish censorship in her article “The Polish Film Industry under Communist Control – Conceptions and Misconceptions of Censorship” thusly:1

The picture painted in the West of the communist control of Polish cinema is therefore far from complete. […] Whether intentionally or otherwise, this tendency has resulted in their interaction being framed as an ‘us and them’ relationship, with filmmakers placed in opposition to Party censors. In reality, this gap was bridged on countless occasions.

In addition, Socialist realism ended in Poland in 1956, precipitated by the death of Joseph Stalin; liberalization in both the Soviet Union and its satellite states strongly encouraged experimental art forms. Yet, socialist aesthetics still drove the film culture of the time. The WFF was supported by the National Film School and a plethora of experimental formats were allowed to be explored as long as they did not directly attack the regime.

The very idea of a workshop suited its members for diverse reasons: it echoed Warholian ideas of an underground artistic “factory”, where the focus was put on the artistic practice of art and the exercises that were done collaboratively. But the idea of a “workshop” also stemmed from the communist idea of film as labor. As in other countries of the Eastern Bloc, for example in Yugoslavia with its kino klub culture, amateur filmmaking was not seen as leisure, it was also not the place of intimate films on private life or family diaries, but an occasion to experiment with film and its meaning, pushing the boundaries and the discoveries of what a non-professional film could achieve. It is interesting to note that some members of the WFF were also involved with another filmic entity outside of the frame of the school, which was the Education Film Studio in Łódź (WFO), where educational films were made with reverence for and mastery of avant-garde techniques – a model exemplified by Wojciech Wiszniewski, an influential figure of the time. Known for his documentary A Story Of A Man Who Filled 55% Of The Quota (Opowieść o człowieku, który wykonał 55% normy, 1973), Wiszniewski ambiguously dismantles the Socialist discourse of rebuilding a ‘radiant world’ after the war by disrupting the relationship between sound and image and thus turning it into a somewhat ironic point of view on the possibility of collective reunification after devastation and war trauma.

Moreover, the WFF was influenced by the historical avant-garde, Polish futurism, and constructivism. The 1930s futurist films of Franciszka and Stefan Themerson had a strong impact on the post-war generation as they were concerned with the short form of poetic film, reducing the literary language of poetry into pure visual form, as seen in the recently rediscovered Europa, adapted from Anatol Stern’s phonic-driven and anti-fascist title-lending poem. Reviving this historical avant-garde, Robakowski pushed further: his clear position was to move away from any form of a linguistic interpretation of cinema. The idea of a linguistic essence of film, that of a “film grammar” allowing us to organize film into linguistic categories (such as phonemes, morphemes, and lexemes), characterized the dominant semiotic discourse of the time, as theorized by Christian Metz in France, for example. As a substitute for the sign, Robakowski preferred talking about the “signal”: as if the beaming of the projector announced the fleeting appearance and disappearance of a latent image. As he noted in 1975 in his paradoxically titled essay “A Language-less Semiologic Concept of Film”:2

As a result of conducted research, the conceptual system can now be seen as an artificial manipulation, an operation that conducts a rape of sorts on the pure cinematic signal. A film recording is a different order of signification than language, and the analysis of film phenomena in terms of linguistic categories is therefore impossible.

According to this train of thought, conceptual cinema pays attention to the expression of signals, and strives towards a semiology of film that is not actually based on language.

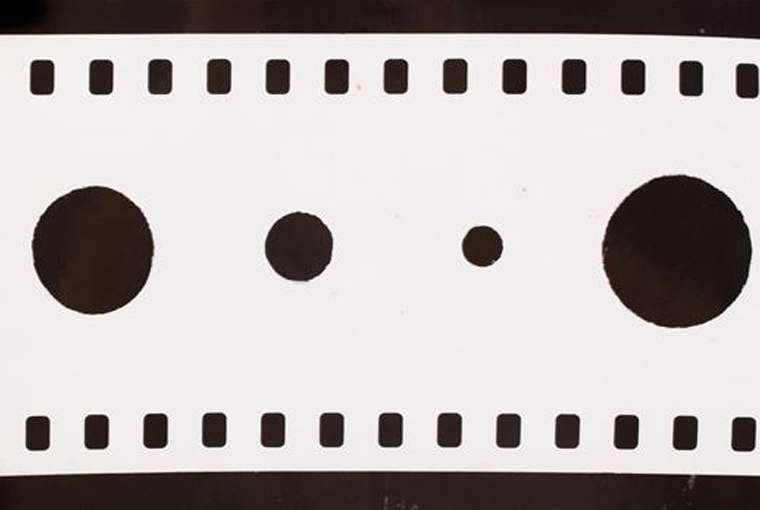

Strategies of dematerialization are usually characterized by conceptual artists moving away from the materiality of painting and sculpting towards a more intellectual understanding of art. However, the fascination with the celluloid medium of 35 mm, film projectors, and later on video technologies, showed that the WFF’s relationship with the moving image was actually quite materialist. Physical interventions such as making holes or drawing crosses, adding geometrical shapes on the reels, cutting out bits and pieces to create collages, and attacking the film with black triangular shapes on the celluloid surface of a cityscape, testify to the fascination with disrupting the image. This conceptual approach to film inscribed in the materiality of the image – an ambiguity manifest in the concept of “obraz” (“image”) that was used by many WFF filmmakers – helped images bleed into figures, icons, faces, or idealistic beauty, which in turn bridged their plastic, sensory, and intellectual aspects.

The minimalist approach of Robakowski enhanced the mechanical function of film; it is not surprising that some filmmakers judged his approach too sterile and lacking in emotional depth. By punching several dozen holes in opaque film stock for his non-camera film Test (1971), he created an eruption of light streaks flickering in the eye of the spectator, who is both hypnotized and attacked. Beauty stripped of ornamentation: the film affects us with an almost primitive fascination with the core mechanical structure of film projection. To enhance this experience, Robakowski would often stand in front of the audience with a mirror, redirecting light streams from the projector leaking through the holes of the film onto the viewers, thereby not only breaking the fourth wall of cinematic projection, but also playing with the liminality of perception. The works of Peter Kubelka or Tony Conrad bring to mind what Józef Robakowski stood for. Kubelka’s black-and-white film Arnulf Rainer (1960) alternates black-and-white film frames to create a minimalist visual experience, while in the US, Tony Conrad’s film The Flicker (1966) also concentrates on the bare minimum of the flicker effect.

The Workshop of the Film Form reinvigorated the radical core of the Polish avant-garde that had known its spark during the futurist period in the post-war context, that is at a time when the successes of historical narratives or Andrzej Wajda’s existential realist style left little room for film abstraction. The WFF is an interesting example of a neo-avant-garde movement that managed to renew the historical avant-garde by pushing its approach into a new formal dimension and initiating a renewal of collective film infrastructure. In his article “What’s New in the Neo-Avant-Garde” about the Western neo-avant-garde wave, the American art historian Hal Foster demonstrates that the term neo-avant-garde, in its very essence, points to a paradox: in search of a new perspective and of innovation, it is also denying its contemporaneity by associating itself with the historical avant-garde of the early 20th century. He states, “I believe historical and neo-avant-gardes are constituted in a similar way, as a continual process of protension and retension, a complex relay of reconstructed past and anticipated future – in short, in a deferred action that throws over any simple scheme of before and after, cause and effect, origin and repetition.”3 In general, neo-avant-garde cinema can be defined as “visionary film”, as Paul Adams Sitney notoriously put it, opening up a propulsive artistic perspective redefining art’s future meaning or even absence of meaning. Yet it also carries a form of nostalgia for the very primitive aspect of cinema when dethroned of its representational content and reduced to light, the machine, and movement.

- Misiak, Anna (2013). “Polish Film Industry under Communist Control: Censorship Conceptions and Misconceptions”. Iluminace, 24 (4), Prague, 61–83; 64. ↩︎

- Robakowski, Józef (1975). Bezjęzykowa koncepcja semiologiczna film u /A Language-less Semiologic Concept of Film. Kat. wyst. Warszawa: Galeria Współczesna (Contemporary Gallery). https://www.lomholtmailartarchive.dk/networkers/jan-swidzinski/1975-11-17-swidzinski-no-7 [Accessed on 15 December 2024]. ↩︎

- Foster, Hal (1994). “What’s Neo about the Neo-Avant-Garde?” October, vol. 70, 5–32; 30. ↩︎

Leave a Comment