Beth Holmgren of Duke University takes a close look at how recent Eastern European cinema is exhuming the cold-war era secret police. In her analyses of Czech, German, and Polish fiction films, she discerns the persistent opposition of a corrupt security apparatus to a dissident intelligentsia that never completely falls from its pedestal. Holmgren shows how exceptional tales of agents’ moral abandon, madness, empathic redemption, and sex-laced manipulation dominate the filmic imaginary in place of what were likely the intriguingly mundane careers and lives of Eastern Europe’s secret others.

The war on terror launched at the beginning of this century has flipped the way Western media portray their national covert affairs. Television series and films now spotlight the social sacrifices and “good vigilance” of the CIA or MI5 agents who would have been blasted several decades back as cynical spies and right-wing spooks. Filmmakers sympathetically track the hard lives of investigators and interrogators – their endless work hours, rocky relationships – for these protagonists may save us from a random embedded enemy poised to strike. They tend to gloss over the criminal excesses of the past and to savor the Cold War as cozy detective fiction.

Not so and perhaps not ever in the case of Eastern European film. The Cold War inflicted far deeper, more crippling scars on citizens in the former Soviet bloc. Filmmakers here are reckoning with the scope of past injustice and complicity rather than valorizing warriors for an uncertain present. After the 1989 fall of the Berlin wall, the gradual opening of state security archives across the region revealed how messy and heavily staffed a functioning police state had to be. In each Eastern European nation, state security employed a sizable labor force and utilized a great many more voluntary and involuntary informants to wage the supposedly pressing battles of the Cold War. The simplistic popular opposition of dissident intelligentsia to secret police thugs does not adequately reflect how people lived vis-à-vis the state in Eastern Europe. Nor does that opposition accommodate the changing historical and local phases of the state-society relationship. Rebellion against a police state status quo erupted at different times in different places and on different scales. Whatever the scope of public protests, the secret police remained a reliable employer, offering stable careers and undeniable material perks.

The thorny questions confronting Eastern European filmmakers today involve representing how these significant secret “others” lived and how they could live with themselves, given the fear they inspired, the antagonism they provoked, and the corruption and unchecked power they enabled, if not initiated. Many state security agents lived long lives doing their jobs, raising their families, socializing with colleagues, and enjoying themselves much as their civilian counterparts did. Where did they work, eat, drink, sleep, and let go? What did their work day entail? What did they think of their careers?

Thus far, a handful of films differently map this previously classified territory. Gábor Zsigmond Papp, for example, lets the Hungarian secret police share their own work details in his 2004 Az ügynök élete (The Life of an Agent), a documentary compiled of training films made by state security during János Kádár’s post-1956 regime.1 These instructive shorts cover a wide array of topics – from surveillance techniques and conducting a home raid to recruiting and running agents. As one reviewer notes, the narration in these films wisely “refrains from overt political comment.”2 What they show is sobering enough. The viewer is directly addressed as a trainee and enticed with close-ups of intriguing gadgets: a frame for positioning a camera in a specially made satchel or purse, a rock-encrusted cylinder for hiding information in the chinks of stone walls. These films also attune the viewer to scan innocuous everyday scenes for spies and surveillance devices. If one didn’t have to denounce and jail people, it would be so much fun to be a secret agent.

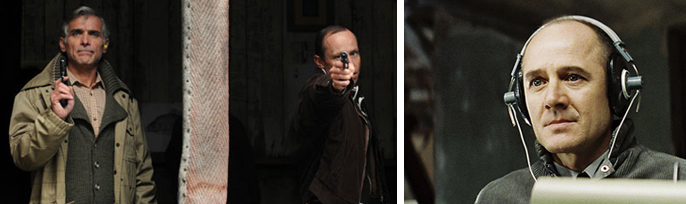

Recent fiction films venture further into this territory and populate it, not only reconstructing the secret habitats of the police, but also resurrecting the agent as star attraction. Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2006 Das Leben des Anderen (The Lives of Others) begins by cleverly aligning our point of view with that of Stasi Captain Gerd Wiesler in a dreary 1980s East Germany. Some may argue that The Lives of Others does not strictly qualify as an Eastern European film, given the filmmaker’s West German roots, but the movie’s plot and sociopolitical context are set exclusively in the German Democratic Republic, and three of its featured actors, including Wiehler, played by Ulrich Mühe, were trained and established in East Germany. At the film’s outset we are immersed in Wiesler’s routine and the “model” ideology and work ethic underpinning that routine. Wiesler is shown ruthlessly interrogating a dissident suspect in prison and then teaching his methods dispassionately to Stasi cadets in a lecture hall. As he eats lunch with his superior in the institutional Stasi cafeteria, his demeanor never sways from vigilance and disapproval while his colleagues (both senior and junior) indulge in political jokes. Wiesler is a frighteningly intelligent, humorless zealot, an agent at the top of his game. Hagen Bogdanski’s camera briskly documents how Wiesler and his crack team bug the home of playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) within a mere twenty minutes. When Wiesler enters the listening post established a floor above, we marvel from his perspective at his formidably outfitted electronic seat of power. To underscore Wiesler’s expertise and dedication, von Donnersmarck’s screenplay pairs him with a buffoonish foil, an affable ordinary surveillance partner who arrives late, tells crude jokes, and is incapable of detecting their prey’s deceptive tactics.

Radim Špaček’s 2011 Pouta (which literally means “handcuffs” or “restraints” in Czech, but is translated as Walking Too Fast) regularly cross-cuts between the storylines of the pursuer and pursued and takes us deeper into the private lives of the Czechoslovak state security in the early 1980s, when Gustav Husák’s post-1968 “normalization” lingered like dirty snow. The secret police protagonist in this film also dominates the interrogation room, but mainly conducts business in the company car, chatting up informants in the back seat. Antonín Rusnák, like Wiesler, is known to be one of the agency’s best men and is partnered with a loquacious goofball named Martin (Lukás Latinák). In comparison with The Lives of Others, Walking Too Fast devotes more attention to the off-duty Rusnák – an intense loner who drinks himself into a blackout at headquarters’ well-stocked bar, jogs alone around the agency’s sports track while his colleagues play soccer, and goes home at night to his comfortable apartment and thoroughly domestic, uninteresting wife. Rusnák’s paternalistic boss worries aloud about keeping his star agent sane and safe within the state security family, where he is to keep serving with “clean hands, a fiery heart, and a cool head.”

Rusnák (with drawn gun) and his boss in “Walking Too Fast” (2010), Wiesler in “The Lives of Others” (2006)

Rusnák (with drawn gun) and his boss in “Walking Too Fast” (2010), Wiesler in “The Lives of Others” (2006)

Both films feature a secret policeman as an unpredictable protagonist, an agent who sooner or later goes rogue. Neither relegates the agent to stereotyped villainy nor develops him as an ordinary man with ordinary appetites and obligations. In The Lives of Others, Wiesler is established as an agent of principle and some autonomy and blossoms into “a good man” of acute sensitivity – a sentimental fantasy made plausible mainly by Mühe’s exquisite acting.3 Mühe plays Wiesler as contained and intent, a consummate professional who speaks only to give orders or to utter Party doctrine without irony. His still, slight body remains at attention. Viewers must read his remarkable eyes for deep sea changes: his disapproval of an operation conducted against Dreyman to satisfy a minister’s lust for the playwright’s lover, actress Christa-Maria Sieland; his growing empathy for and intervention on behalf of Dreyman and Sieland as they resist the minister’s blackmail and Dreyman slips into political dissidence; and the urgent adoration he communicates to Sieland as he struggles to save her from moral suicide. The screenplay speeds Wiesler towards his saintly conversion, never freighting him with romantic or familial complications and ultimately expiating him of his Stasi sins with professional demotion. Nonetheless, it is preposterous to envision a seasoned Stasi officer converted into a dissident-loving secret savior in the mid 1980s, as Anna Funder, author of Stasiland (1996), argues in her careful review of the film. The Stasi system, with its complex system of agent-on-agent surveillance, permitted no such maverick operations. It was for just this reason that Dr. Hubertus Knabe refused von Donnersmarck permission to shoot the film at the Hohenschönhausen, the former Stasi political prison which Knabe now directs as “a memorial museum about the regime.”

In Walking Too Fast agent Rusnák travels a very different trajectory at the out-of-control speed signaled in the film’s English title. Played fearlessly by Ondřej Malý, Rusnák is small, tough, and tightly wound, a man who suddenly explodes in violence or implodes with the onset of panic attacks. In an interview with Radio Prague, Špaček explains that he based his casting of Malý on their previous work together: “He played a lunatic, and when I saw him, I thought that he was real, that he wasn’t an actor.”4 Malý’s face is affectless, unreadable, and unsympathetic. Whereas Mühe’s eyes in close-up drew us in, Malý’s opaque face and restless body keep us guessing and anxious, a response we share with everyone else in the film. Tomás Vtípil’s edgy techno metal score reinforces this mood. Walking Too Fast inserts more psychological information about its agent, little red flags that might explain his recent bizarre behavior. Rusnák, his wife, and Martin all hail from the provinces; Rusnák’s admission into the secret police was his ticket to the big city, far from his dead-end roots. A visitor from home remarks on Rusnák’s resemblance to his father, an abusive misanthrope. In a rare moment of exposed vulnerability with his wife, Rusnák remembers how he and a friend (now a confirmed wife beater) loved the risk of jumping into a flooded quarry, leaping into its black chasm.

Walking Too Fast leaves us with this chicken-and-egg argument undecided: It will never be clear if Rusnák became a secret policeman because of his psychological predisposition or if excelling at interrogation, torture, and digging up dirt on his compatriots warped him into such a taciturn, pitiless hunter. But Ondřej Štindl’s screenplay clearly treats the protagonist as a study in progressive insanity, conveying through Rusnák’s rushed, disjointed monologues that he is agitated by knowing too much and by finding so little satisfaction in that knowledge.

Rusnák’s fall from grace, unlike Wiesler’s, has nothing to do with the siren call of the intelligentsia. He steps off the grid of regular police work because of his obsession with Klára Kádlecova (Kristina Farkasová), the working-class lover of a married dissident doctor, Tomás Sýkora (Martin Finger). When surveillance tapes record that Kádlecova, a crane operator, feels herself to be above it all on the job, Rusnák thinks he has discovered his soulmate, his partner in escape. Sýkora is not worthy of her love. In sharp contrast with the dissidents haloed in The Lives of Others, Sýkora and his friend, the writer Pavel Vesely, emerge as callow or complicit. Sýkora is a self-indulgent adulterer, put firmly in his place during the scene when his loyal, pretty wife lashes out at him about the affair. The arrogant Vesely spends most of his time onscreen in the company of Rusnák and Martin, informing on his friends while pretending that he is besting the authorities with his intricate mind games. Rusnák’s deluded pursuit of Klára speeds up his disintegration as he beats and bullies Sýkora into exile, throws his own wife out of their home, abandons his job and his partner, and uses Vesely to set up a doomed tryst. By the end of this color-drained film, masterfully shot by Jaromír Kačer, the chasm once again beckons to Rusnák and it is now radiant with obliterating light.5

Despite their different sensibilities, The Lives of Others and Walking Too Fast both aim to divest the agent of his socially toxic job and to distinguish him as an exceptional case. They present viewers with an impossible Stasi turned saint and an impenetrable madman, two model agents who break down due to empathy or abject nihilism. Špaček’s film does feature Martin, a regular guy whose drinking, skirt-chasing, and general good humor offer comic relief as well as a foil to the disturbing Rusnák. Easily the most entertaining episode in Walking Too Fast showcases Martin – cheerful, inebriated, and shameless – leaping onto the bar in police headquarters, stomping on the glasses and plates, and imitating his favorite rock stars.

Sex and the Secret Policeman

Little Rose preserves some of the details of this unnerving romance: Jasienica’s importance as a supporter of the student protesters, his prominent membership in Poland’s PEN Club, his wife’s cover as a secretary at Warsaw University. But the screenplay, by Kidawa-Błoński and Maciej Karpiński, at once complicates the plot, streamlines the wife’s role, and heats up the screen by adding a sexy secret policeman to the principal players. This policeman, Roman Różek, seduces and bullies his girlfriend Kamila into informing on a famous writer, ostensibly to advance his career and ensure their future together. Roman’s profession and his manipulation of Kamila render her a pawn, then a victim, and, finally, a heroine. Once Kamila comes to love her target, professor and writer Adam Warczewski, she retreats from Roman and refuses to produce any more reports. In many ways, Little Rose devolves into predictable melodrama.

Yet the character of Roman, as realized by Robert Więczkiewicz, is that of a lovelorn, conflicted brute. Więczkiewicz excels in incarnating ambiguity, be it as the temperamental agent in Little Rose or the crude sewer worker who is reluctantly convinced to save Jews in Agnieszka Holland’s 2011 W Ciemności (In Darkness). Roman turns out to be a man of ambition and a man with a secret. At the outset Kamila and Roman match each other well in youth, good looks, sexual appetite, and working-class notions of the high life. Kamila, played by the physically stunning Magdalena Boczarska, is an orphan who intimates that she was abused as a child; Roman’s possessiveness and apparent success attract and reassure her. When Roman admits her into his apartment, located in a special gated compound, and shows off his boxing trophies and, at her request, his gun, Kamila is genuinely impressed and he is genuinely proud. The scene reveals something of his motivation to join the force, where his zeal, strength, and loyalty will reap him considerable material rewards.

Once Kamila consents to inform under his supervision, their work together initially gives them a sexual rush. The code name she chooses, “Little Rose,” is Roman’s term of endearment for her. He greets her with roses at their rendezvous. Serving as an informant constitutes the next best phase in Kamila’s limited education, a higher rung up the socioeconomic ladder. Just as Roman is an athlete become officer, so Kamila is a secretary become “writer,” a young woman who eagerly types up reports late into the night. These close-up shots of a bespectacled excited “Little Rose” at her typewriter intimate how empowering and addictive such a secret job would be for the right candidate.

Unfortunately, Little Rose does not take the same risks in developing Jasienica’s surrogate. The writer Adam Warczewski (Andrzej Seweryn) never slips from his high dissident pedestal, even when he falls for the much younger Kamila. The film settles for a battle between two men over a woman’s soul and exceptionally lovely body. Adam introduces Kamila to high culture – fine wine, forbidden Polish literary classics, the comforts of a bourgeois intellectual’s home, and a ready-made family in his gracious mother and precocious young daughter. He impresses Kamila as an eloquent professor and positively takes her breath away when he speaks out in support of the young democratic forces at work in Poland during a PEN Club meeting. That speech decides Kamila to quit the force. Despite their substantial difference in age, even Kamila’s lovemaking scenes with Adam are more tender and satisfying than sex with the macho Roman. After toying with Kamila’s attraction to secret police work, the screenplay sends her to Adam’s intelligentsia finishing school and scrubs her soul clean. Kamila marries Adam only after he has learned of her role in his police persecution. The two join together with eyes opened, unlike the actual Jasienica and his wife.

As one might expect, Adam’s unvarying nobility boxes Roman into a more villainous part, and he plays Caliban to Adam’s Prospero. Though Roman pushed Kamila to become intimate with the treasonous “Jewish” intellectual Warczewski and supply him with valuable counterintelligence, the secret policeman flares up every time he hears of their intimacy. Roman savagely beats a man who calls Kamila a whore at their nightclub hangout, and he tries to maintain his primacy in her affections through rougher and rougher sex, until she balks at his attempted rape. He plans to prevent her marriage to Adam by confronting the professor with Kamila’s written pledge to serve as an informant. After their marriage it is strongly intimated that Roman kills Adam by staging his fall from a second-story balcony. He leaves a rose as his calling card. The film inexorably reduces Roman’s character from ambitious professional to primitive thug.

Yet the final revelation of Roman’s secret exposes the source of his conflict and complicates his brutality. Roman initially lied to his superior about his relationship with Kamila out of fear. As the political witch-hunt for Zionists heated up, Roman volunteered his lover’s services to prove his loyalty, to deflect any suspicion that he was in fact a Jew. The anti-Semitic venom that Roman first heaped on Adam when he describes him to Kamila stems from self-hatred, his fervent desire to pass as a “Pole” (read Polish Gentile) and to make good in the force. After some hesitation, Kamila complies with his plans, yet Roman can’t control his feelings about her doing so. Ultimately, Roman’s desire for Kamila, at odds with her work as an undercover informant, drives him to blow the operation and then destroy a man who is key to the dissident network at home and abroad. Disguising and denying his Jewishness results in its exposure and his deportation, along with thousands of other purged “Zionist” Jews and state security officers in 1968. In the final scene, when the widowed Kamila goes to the train station to watch his departure from afar, Roman’s half smile in her direction conveys many possibilities – pleasure at her bothering to come, vengeful satisfaction that he has vanquished his rival, rueful farewell, and abashed acknowledgment of the complex person he is. Więczkiewicz plays Roman as a lover and a victim as well as a brute, and one wishes that there had been much more to his potentially intriguing story.

As its title alerts us, the film Reverse does not adhere to clichéd notions of good and evil, the noble and the ignoble, though its Stalinist setting outfits it well for melodrama. The cast includes all the usual suspects – Communist Party-aligned bureaucrats, secret policemen, and three generations of an intelligentsia family who could be victimized as class enemies. What reverses this familiar scheme is Andrzej Bart’s brilliant screenplay in which high romance collides with base reality, a marriage comedy with a thriller. Almost all the characters end up with dirty hands.

Reverse evolves out of the Romantic fantasies of its heroine Sabina Jankowska (Agata Buzek), a tall, gawky poetry editor and thirty-year-old virgin. It seems that Sabina is doomed to miss out on sexual intimacy altogether, though not of her own volition. The film’s opening scene focuses on Sabina’s rapt reaction shots in response to a propaganda film showing scantily clad young men doing calisthenics. Stalinist newsreels featuring athletic bodies most nearly approximated pornography in early 1950s Warsaw. Sabina feels an even more intense sexual thrill when she dresses up as an ice skater, joining other publishing house employees uniformed as athletes for a political parade. Flattered by her flirtatious boss, Sabina later takes stock of her equipment at home, touching her breasts and raising her short skating skirt above her crotch as she gazes in the mirror. She is more than ready for a grand passion.

Sabina also senses that she has let the moment of grand heroism pass her by. She did not fight (in her words, “shoot”) in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising that left the city in ruins. She reveres a poet who survived in those ruins and resists any attempts to revise his work so that it might be published; he would rather starve than submit to a repressive Stalinist state. Sabina’s pathetic variation on such heroism involves her daily swallowing and excreting a foreign gold coin that the state forbids private citizens to keep. In lieu of any bold public act, she defies the government with the base hiding place of her digestive tract, though she sometimes dramatizes her “internal dissidence” by playing a tragic operatic aria as soundtrack while she swallows the coin. In one such scene, the camera grants her the diva’s spotlight, shooting her solemn self-aware movements from high above.

In the meantime, Sabina’s grandmother and mother Irena crank a marriage plot into place, hoping to net Sabina a husband. Her mother tempts suitors to their home with her cooking, baking, and distilled liqueurs. Played deftly by Krystyna Janda, Irena is a dab hand in the kitchen since she owned a drugstore before the war; her cabinets are as well-stocked as a witch’s pantry. Sabina’s charms really amount to what Irena lays out on the table. Two dinner guests, the hero-poet and an accountant suitor, wax most enthusiastic about Irena’s cake. Unfortunately, Sabina’s one traumatizing glimpse of real-life intercourse reinforces this equation: she catches her boss screwing a secretary who lies inert across his desk.

This lengthy detour into Sabina’s fantasies and disappointments explains why the appearance of a secret policeman fools her as a miracle, the arrival of a white knight in period dress. The period in this case is a film noir version of Stalinist Warsaw, elaborated in sharp contrasts between light and shadow, urban nightscapes, eerily lit faces, creepy wide-lens close ups, and the claustrophic framing of characters in doors, windows, or entrapping maze shots filmed from above.7 Cinematographer Marcin Koszalka and Lankosz’s camera, production, and music crew have fashioned Reverse into an archly ironic masterpiece, replete with cinematic quotations and sound cues. Dressed in a tough guy trenchcoat, Bronek Falski emerges from the shadows like a younger, hatless Humphrey Bogart and saves Sabina as she is being robbed by two petty thieves. Played by rising star Marcin Dorociński, this mysterious stranger is handsome, sexy, and smooth, tailor-made for Sabina’s grand passion. In an ingenious gambit, Reverse hooks a cultured young woman, a lover of poetry and valor, with a secret policeman groomed and programmed to be her homme fatale.

Roman in “Little Rose” (2010), Sabina and Bronek in “The Lives of Others” (2009)

Roman in “Little Rose” (2010), Sabina and Bronek in “The Lives of Others” (2009)

Like Roman in Little Rose, Bronek plans to seduce Sabina into informing, yet he must feign desire, pass muster with her mother, and promise her marriage. He courts her with clichés — afternoon tea, kisses in the rain, and fast-talking lies about his war record and his vague pursuit of different studies. He poses as a working-class veteran who aspires to better himself. Bronek delivers these lines as if they were excerpts memorized from different scripts. Viewers are on to his game long before Sabina is in a state to understand. Dorociński gives a virtuoso performance in his final meeting with Sabina, when all three Jankowski women believe he will pop the question. Speeding up his courtship out of revulsion or ignorance, Bronek makes crude advances on Sabina and finally takes her on the table usually topped with an enormous cake, swilling Irena’s liqueur as he thrusts himself into his “fiancée.” As he closes in on his prey, Bronek’s smooth façade cracks. He owns up to his provincial background, sucks inelegantly on his teeth, and veers between mawkish and brusque in his patter. A still compliant Sabina listens to his ramblings until he pops a very different question about her helping him with his work, at which point she recognizes him as the enemy. Unveiled, Bronek threatens her with all the goods he has on her and her family, including her peculiar method of coin hoarding, and Sabina faces her greatest moral challenge.

This challenge galvanizes the timid, intellectual, family-oriented daughter to become Kamila’s opposite: Sabina chooses death – more precisely, homicide — over collaboration. Taking advantage of her mother’s pharmacological inventory, she poisons Bronek and is prevented from shooting herself only by her mother’s fortuitous return. (Sabina never gets her gun.) Bronek’s dying is messy and prolonged. A hand-held camera tracks his convulsions, lurches, vomiting, and paralysis, dwelling on the visceral crime of Sabina’s “heroism.” The film’s sudden transformation into a thriller focuses on how three respectable women succeed in dissolving the corpse of a secret policeman and disposing of his effects and bones. Sabina and Irena, with advice from the grandmother, disembody Bronek with scary efficiency. Irena uses more of her potions on the agent’s flesh, covering his rapidly decaying body with her son’s uplifting socialist realist canvasses – a nice Baroque juxtaposition. In desperation and perhaps deference, Sabina buries what remains of her agent-seducer in the foundation of Warsaw’s most Stalinist landmark, the Palace of Science and Culture. On this fictional page of Stalinist history, a modest matriarchal intelligentsia “disappears” a member of the secret police.

Yet the film’s motif of ingestion – cake, liqueur, gold coin, poison – boomerangs on Sabina’s body. Bronek has impregnated her. Over Sabina’s objections, mother and grandmother persuade her to keep the child, already imagining an improved biography for its dead father. “Perhaps he fought against Hitler,” Irena speculates. Once the film has established that Sabina’s baby is born on the day of Stalin’s death, it leaps forward a half-century to the son’s reunion with his aged mother on All Saints Day. The final scenes, filmed in color, explain the color flash forwards previously interspersed. Reverse thus conjures up the cleverest and most chilling transformation of the secret policeman. Sabina and Bronek’s son, played again by Dorociński, has his father’s good looks and a thoroughly updated version of his mother’s intelligentsia values. He is an affluent gay architect who lives in the United States, cherishes his mother, and brings his lover to visit his largely deceased Polish family.

The final scene of Reverse shows a hunchbacked Sabina commemorating Bronek’s grave, unbeknownst to her son. She places a candle strategically beside a statue of a strapping young man at the Palace, reinforcing the film’s link of Stalinist athleticism with the sexual thrill Bronek once promised. In every other particular, Sabina has replaced Bronek’s identity with that of a Romantic nationalist who fought in the Uprising and has raised their son to be Bronek’s opposite in sophistication, sensibility, sexuality, and class. The thriller delivers a highly ambiguous verdict on the dissident intelligentsia. Since the Jankowskis could not redeem Sabina’s agent fiancé, they used all their arts to annihilate him. When the agent left a seed of himself in Sabina, they treated it as raw material to cultivate into their rendition of a model man, one who had to be shielded from the real past and the crimes of both his parents.

None of the four fiction films analyzed above try to imagine the making of an unexceptional agent, the graduate of the training conducted in Papp’s documentary. The Cold War duel between dissident intelligentsia and state security still casts a potent spell. In The Lives of Others, Little Rose, and Reverse, the intelligentsia trumps the secret police in class and culture, though Reverse does not cede them the moral high ground. The films that flesh out the character of the secret other highlight, on the one hand, his limitations in background and education and, on the other, his overweening ambition. If the agent does not switch to the side of the angels, then he is doomed to deportation, insanity, or murder.

There are obvious reasons for the secret policeman’s continuing onscreen punishment in Eastern European film. The damages that state security inflicted on ordinary citizens in Eastern Europe remain too fresh, even for younger filmmakers (Špaček, Lankosz) who remember only their parents’ repression. It’s worth reiterating here that von Donnersmarck, the one director who redeems his agent, grew up in West Germany. The Czech and Polish directors share their parents’ judgment and disdain. As Špaček acknowledges, only his screenwriter had contact with former agents: “[Štindl] actually met one or two guys who used to work for the secret police, the StB. But it was just a proof of how empty these people were and how much more they liked partying and getting drunk than working. But that’s only a funny story that wasn’t that important.”8

Yet there is a strong case to be made for tracking the lives of secret others in much greater detail, given their endurance in and impact on the system. Dismissing agents as evil, empty, or unimportant blinds viewers to the uncomfortable facts of their complicated existence, the multifaceted parts they played in shaping postwar Eastern European reality. What sorts of people were drawn to serve? Did they join the force for ideological, material, or psychological reasons? What relationships did agents cultivate with their unknowing neighbors and acquaintances? What sorts of lives did they lead with their parents, siblings, spouses, children, and grandchildren? What did they discover and what did they change in the society they spied on? There remain so many intriguing questions to be explored — not for the purposes of exonerating the secret police, but towards more accurate and complex exposure of a police state society. Perhaps only the next generation of Eastern European filmmakers will be willing and able to rummage in this Pandora’s box for precisely such important, disturbingly ordinary stories.

Leave a Comment